In mid-December, 2020, 30.2 percent of adults in the U.S. reported symptoms of depression. During the first week of May this year, that number dropped to 22.0 percent. Although that is a significant improvement, it still means that just over 1 in 5 adults are experiencing symptoms of depression. Advances in understanding depression are not so common. A newly-published study, however, adds breakthrough information which may improve management for sufferers.

Researchers at the University of British Columbia showed, for the first time, what takes place in the brain with a depression treatment known as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

With rTMS, a device with an electromagnetic coil is placed against a patient’s scalp. It stimulates nerve cells in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which are involved in mood control. It has proved effective, but how it affected the brain was not clear.

Depression, of course, can be resistant to treatment; up to 40 percent of people with major depression do not respond to antidepressant medications. When the condition is unrelieved by typical treatments, rTMS may be recommended.

“We wanted to know what happens to the brain when rTMS treatment is being delivered,” says Dr. Fidel Vila-Rodriguez, an assistant professor in the University of British Columbia’s department of psychiatry, in a statement.

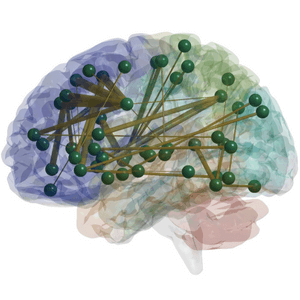

Dr. Vila-Rodriguez and his team delivered one round of rTMS to patients while they were inside a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner. They found that stimulating the dorsolateral pre-frontal cortex also activated other regions of the brain involved in multiple functions — emotional responses, memory, and motor control.

The participants then underwent four weeks of rTMS treatment, after which the team assessed whether the activated regions of the brain were associated with patients having fewer symptoms of depression.

“We found that regions of the brain that were activated during the concurrent rTMS-MRI were significantly related to good outcomes,” says Dr. Vila-Rodriguez.

With this new map of how rTMS stimulates different areas of the brain, Dr. Villa-Rodriguez hopes the findings can be used to determine how well a patient is responding to rTMS treatments.

“By demonstrating this principle and identifying regions of the brain that are activated by rTMS, we can now try to understand whether this pattern can be used as a biomarker,” he says.

Dr. Vila-Rodriguez is now exploring how rTMS can be used to treat a range of neuropsychiatric disorders. He is looking at rTMS to enhance memory in patients who are showing early signs of Alzheimer’s disease. He is also studying whether the rTMS brain activation patterns can be detected by changes in heart rate.

Health Canada approved rTMS for use 20 years ago, but it is still not widely available. In British Columbia, some private clinics offer rTMS, but it is not covered by the provincial health plan. Dr. Vila-Rodriguez hopes that this type of research will encourage widespread accessibility of the treatment.

The research is published in the American Journal of Psychiatry.