As we age, it’s normal to occasionally misplace our keys or forget an appointment. But for some people, these “senior moments” may be an early warning sign of more serious cognitive problems down the road, like Alzheimer’s disease. The challenge is detecting these subtle changes before they show up on standard tests. Now, researchers at Concordia University have developed a new approach that could help spot the initial stages of cognitive decline — even when a person’s symptoms are so mild that they don’t show up in clinical evaluations. The secret lies in looking at the brain as an interconnected network, rather than testing individual abilities in isolation.

The study, published in the journal Cortex, was led by psychology professor Natalie Phillips and her doctoral student Nicholas Grunden. They used a technique called network analysis to examine data from two large Canadian studies on aging and cognition.

An early diagnosis of cognitive decline can be difficult to assess because of the vast complexity of the brain. Standard tests often fail to pick up on subjective cognitive decline (SCD), where a person reports concerns about their memory but still scores normally on evaluations.

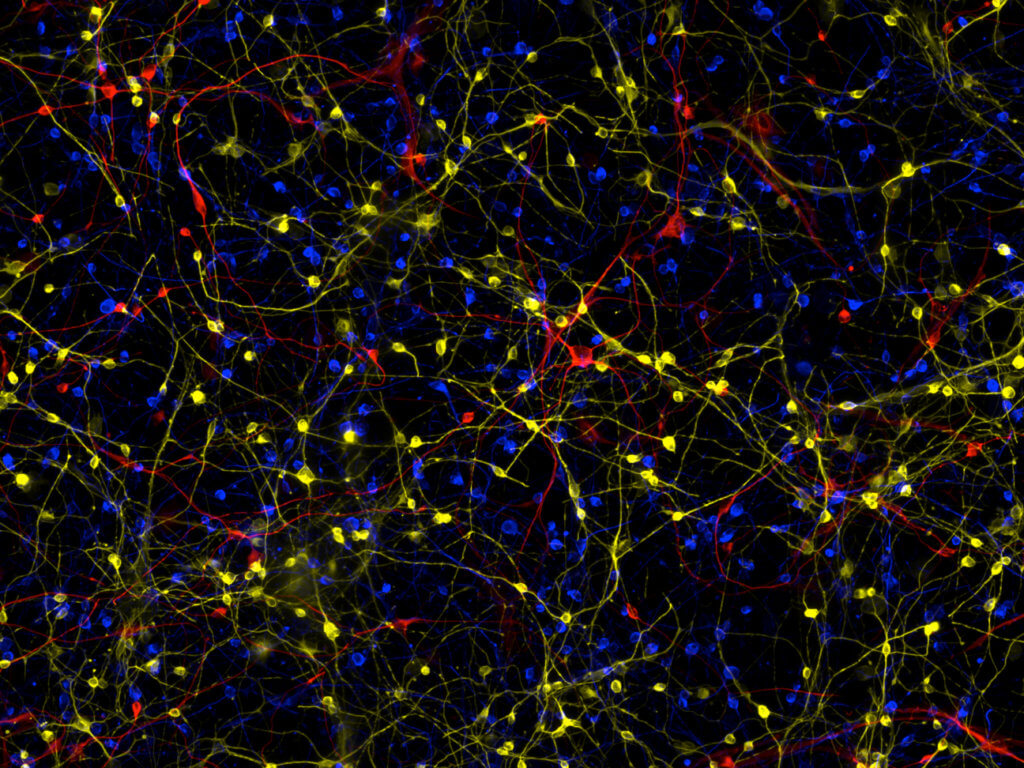

To get a more sensitive picture, researchers modeled participants’ performance as a web of interconnected cognitive abilities. Think of it like a social network, but instead of people, the “nodes” are things like memory, language, and processing speed. The “edges” are the strength of the relationships between these mental skills.

By comparing the networks of people classified as cognitively normal, with SCD, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or Alzheimer’s disease, distinct patterns emerged.

“The nodes are connected by edges, which are the conditional associations between them,” says Grunden in a media release. “The edge reflects how those variables work together. Are they positively correlated or negatively correlated? The network shows us how strong these associations are by how saturated the edges are. It’s a built-in visual communication of findings.”

Two core abilities — executive function and processing speed — emerged as highly influential hubs in the cognitive networks. Both are known to dip with normal aging. But the analysis revealed a telling gradient: these hubs progressively weakened from the cognitively normal group, to those with SCD, to those with MCI.

“We found that very interesting, because it uncovered something that speaks to individuals’ subjective concerns that are invisible in normal statistical analyses,” explains Grunden.

“Executive function and processing speed are important cognitive abilities in that they contribute to other abilities (e.g., language, attention) and are integral to supporting an individual’s day-to-day functioning in their lives. We know efficiency decreases as we age but we also see them at the initial stages of some types of progressive cognitive decline.”

This positions SCD as a potential transition stage between healthy aging and the first clinical signs of impairment. It suggests that self-reported changes in day-to-day functioning could indeed be capturing meaningful alterations in the brain’s wiring.

The influence of age itself also seemed to shift along this continuum. It was a strong predictor of cognitive performance in the normal and SCD groups, but that relationship diminished in people with MCI or Alzheimer’s.

“In other words, all things considered, age will be the biggest influence on cognition for older adults who do not show signs of Alzheimer’s disease,” notes Phillips, the Concordia University Research Chair in Sensory-Cognitive Health in Aging and Dementia.

“But that is not the case in those individuals who have a diagnosis of MCI or Alzheimer’s disease. For them, cognitive function is more associated with how advanced their disease is, as indicated by general measures of clinical status on standardized cognition tests like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test.”

Grunden sees network analysis as a powerful tool for studying the brain as a holistic system, rather than through a reductionist lens.

“This helps us read between the lines, because we can look at the interrelationships between all of the variables at the same time,” says Grunden. “You can pick up on indicators that are less apparent in single elements of data and instead focus on associations between them.”

The ultimate goal is to develop better methods for early detection of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. While there is still no cure, prompt diagnosis is crucial for planning and accessing support services. Lifestyle changes and cognitive training may also help slow progression in the beginning stages.

It’s a promising step towards unraveling the complexities of the aging brain — and giving people more tools to maintain their cognitive health for as long as possible.