Humans and nonhuman primates (in this study, chimpanzees) have remarkably similar brains. Significant dissimilar features of the human vs. chimpanzee brains are the structures known to be associated with the use of language. The pertinent anatomy in humans is larger, more complex, and connected to more areas which are farther-reaching within the brain than in chimpanzees.

“At first glance, the brains of humans and chimpanzees look very much alike. The perplexing difference between them and us is that we humans communicate using language, whereas non-human primates do not”, says co-leader Joanna Sierpowska, Radboud University in the Netherlands, in a statement.

Previous research examined a nerve tract in the frontal and temporal lobes called the arcuate fasciculus. ”We wanted to shift our focus towards the connectivity of two cortical areas located in the temporal lobe, which are equally important for our ability to use language,” says Sierpowska.

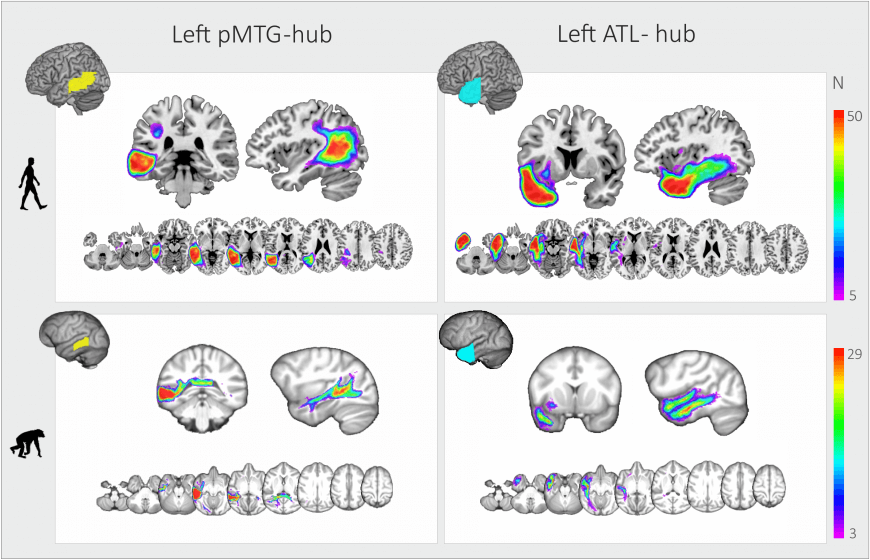

The researchers examined scans of 50 human brains and 29 chimpanzee brains, scanned in a way similar to humans, but under well-controlled anesthesia.

They explored the connectivity of two language-related brain hubs (the anterior and posterior middle areas of the temporal lobe), comparing them between the species. “In humans, both of these areas are considered crucial for learning, using and understanding language, and harbor numerous white matter pathways,” says Sierpowska. “It is also known that damage to these brain areas has detrimental consequences for language function. However, until now, the question of whether their pattern of connections is unique to humans remained unanswered.”

The researchers say that the connectivity of the posterior middle temporal areas in chimpanzees is confined mainly to the temporal lobe. In humans they also found previously unknown connections to the frontal and parietal lobes.

“The results of our study imply that the arcuate fasciculus surely is not the only driver of evolutionary changes preparing the brain for a full-fledged language capacity”, says co-author Vitoria Piai, also at Radboud University.

Piai continues, “Our findings are purely anatomical, so it is hard to say anything about brain function in this context, but the fact that this pattern of connections is so unique for us humans suggests that it may be a crucial aspect of brain organization enabling our distinctive language abilities.”

Comment from Dr. Faith Coleman

The most useful remark in the original article is Piai’s assertion, “It is hard to say anything about brain function in this context.” For this study, brain scans performed without anesthesia cannot be equated with brain scans performed under anesthesia, no matter how “well-controlled” the anesthesia, no matter the species.

Sierpowska said: “However, until now, the question of whether their pattern of connections is unique to humans remained unanswered.” Her statement suggests that the question has been answered. It cannot be said that the pattern of connections found in the human brains in this study is unique to humans. It cannot be extrapolated from these results that the pattern of connections is present in all humans and only humans. It can be said that the connections of interest were seen in 50 human brain scans but were not seen in 29 chimpanzee brain scans.

There are additional flaws and faulty interpretations of data in this study.

Wouldn’t it be interesting to compare the areas of human and chimpanzee brains which are associated with social civility? Which would be larger and more complex? What might we learn?