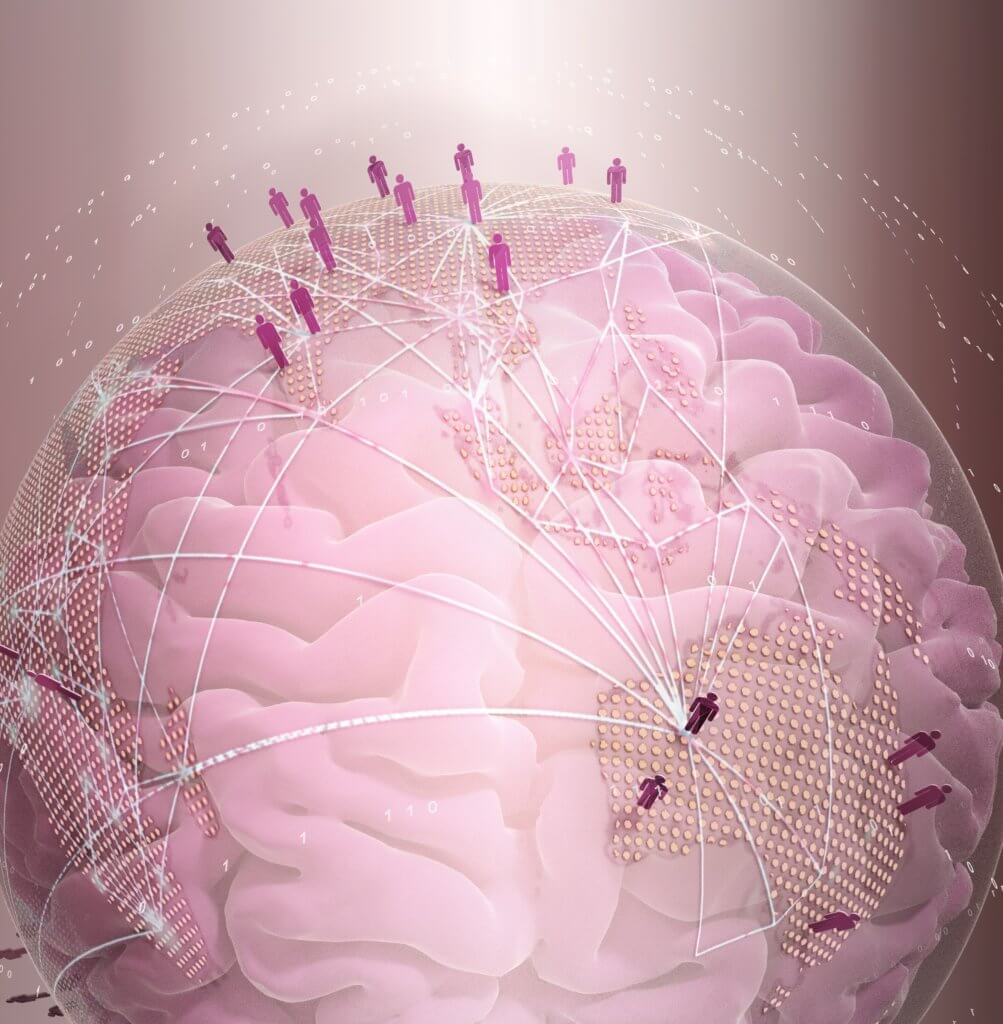

Could brain structure explain why some young people decide to take their own lives? Researchers from the University of Southern California report that teens and young adults with suicidal thoughts and behaviors have small changes to the size of their prefrontal cortex — an area involved in logic and decision-making.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death for people between 10 and 33 in the United States. The number of suicide attempts among underaged adolescents has increased, despite national suicide prevention efforts. To create better interventions, neurologists are looking into suicidal brains to get some answers.

The study was an international collaboration between neuroscientists, psychologists, and psychiatrists that pooled together data on suicidal behaviors among young people. Suicidal ideation is typically associated with other mental health conditions, such as mood disorders. The large dataset allowed researchers to analyze different groups depending on their conditions.

“Benefitting from the large dataset that we had available, we were able to perform analyses in multiple subsamples,” explains Laura van Velzen, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Centre for Youth Mental Health at the University of Melbourne and lead author on the study, in a statement. “We started with data from a smaller group of young people with mood disorders for whom very detailed information about suicide was available. Next, we were able to look at larger and more diverse samples in terms of type of diagnosis and the instruments which were used to assess suicidal thoughts and behaviors.”

The results showed subtle changes to the size of the frontal pole, a prefrontal region, among young people with mood disorders and suicidal thoughts. “Besides revealing subtle alterations in prefrontal brain structure associated with suicidal behavior in young people, our study shows the strength of combining data from 21 international studies and the need for carefully harmonizing data across studies,” adds van Velzen.

Because the neurological changes were tiny, the study authors suggest the brains of people with suicidal behaviors differ little from people without such history. However, they note the subtle differences in the prefrontal lobe could provide a potential mechanism of action driving suicidal behavior and potential targets for suicide prevention strategies.

“The study provides evidence to support a hopeful future in which we will find new and improved ways to reduce risk of suicide. It is especially hopeful that scientists, such as our co-authors on this paper, are coming together in larger collaborative efforts that hold terrific promise,” says Lianne Schmaal, PhD, an associate professor at the University of Melbourne and coauthor of the study.

The study is published in Molecular Psychiatry.