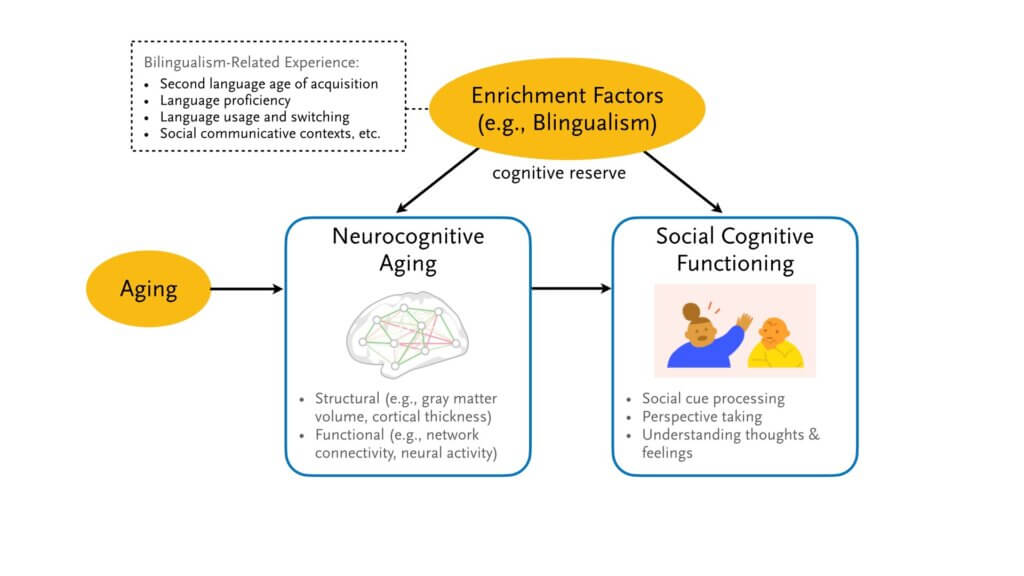

Being bilingual is much more than learning a second language — it keeps your brain healthy. The ability to understand the mental states, beliefs and emotions of others, known as “theory of mind,” is a key aspect of social cognition that tends to decline with age. But a new study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, suggests that becoming bilingual early in life may help preserve these important social skills as we get older.

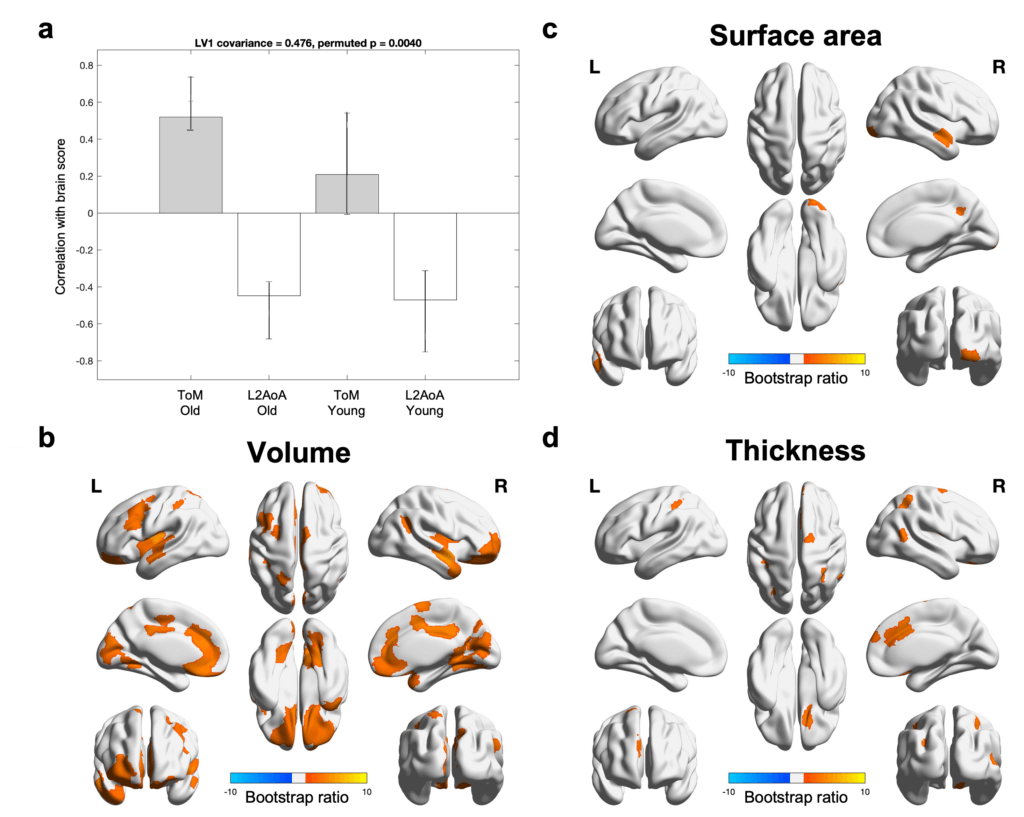

Researchers at Singapore University of Technology and Design and National University of Singapore compared the brains and social cognition abilities of 46 young adults and 50 older adults, all of whom spoke at least two languages fluently. They found that across both age groups, learning a second language at a younger age was associated with better performance on tests of theory of mind.

When peering inside the brains of the participants using MRI scans, scientists discovered that those who acquired their second language earlier had increased gray matter volume, thickness and surface area in several brain regions linked to language, cognitive control, and representing the mental states of others. This brain-cognition association was stronger in the older adults compared to the younger group.

In essence, it seems that early bilingual experience may promote the development of extra “gray matter reserves” in key brain areas during youth. Then, as the brain begins to naturally lose gray matter volume and experience cognitive decline with aging, those with more of this reserve built up from childhood can maintain their social cognition abilities for longer.

“These reserves highlight the brain’s flexibility and resilience. An individual with greater reserves is likely to maintain good cognitive function in aging,” says study co-author Yow Wei Quin, professor at the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), in a media release.

Researchers propose that learning and juggling multiple languages from a young age engages regions of the brain involved in theory of mind more heavily and frequently. This increased activity over time may drive beneficial structural changes in the brain. Just as physical exercise builds muscle, regularly “working out” these brain areas with the mental demands of bilingualism can bulk them up.

What exactly is this “theory of mind” that bilingualism seems to protect? It’s the intuitive understanding that other people have their own mental states, knowledge, motivations and beliefs that can differ from one’s own. We use it constantly to interpret social cues, predict behaviors, empathize with others, and navigate social interactions. Without it, relating to people and functioning in society becomes very difficult, as seen in disorders like autism.

Theory of mind skills usually begin developing in early childhood and are thought to peak in young adulthood before gradually declining with age. This decline can make it harder for older adults to “read” people, detect deception, and see things from others’ perspectives. But lifelong bilinguals seem more resilient to this deterioration of social cognition.

“Such structural and functional changes result in an age-related decline in cognitive function, affecting language, processing speed, memory, and planning abilities,” notes Yow.

Researchers suggest it’s never too late to learn a new language and reap some cognitive benefits. But their findings indicate that picking up that second language in early childhood may be especially advantageous for maintaining sharp social skills into old age.

Of course, becoming bilingual isn’t the only way to preserve mental function over time. Engaging in any cognitively stimulating activities, staying physically active, eating a healthy diet, and maintaining strong social connections can all help keep the brain in tip-top shape. But for those who have the opportunity, learning a second language may give an extra boost to those critical theory of mind abilities.

The study does have some limitations — it looked at brain structure, not function, and only examined people at one point in time rather than tracking them across the lifespan. Researchers state that more long-term research is still needed to prove that early bilingualism actually causes improved preservation of social cognition with aging.

Still, as populations worldwide grow older and age-related cognitive decline becomes an ever-greater concern, these findings offer an intriguing suggestion that the languages we learn as children may help shape the social skills and brain health we carry for life. In an increasingly globalized, connected world, that’s just one more reason to raise the next generation with the power of two (or more!) languages.