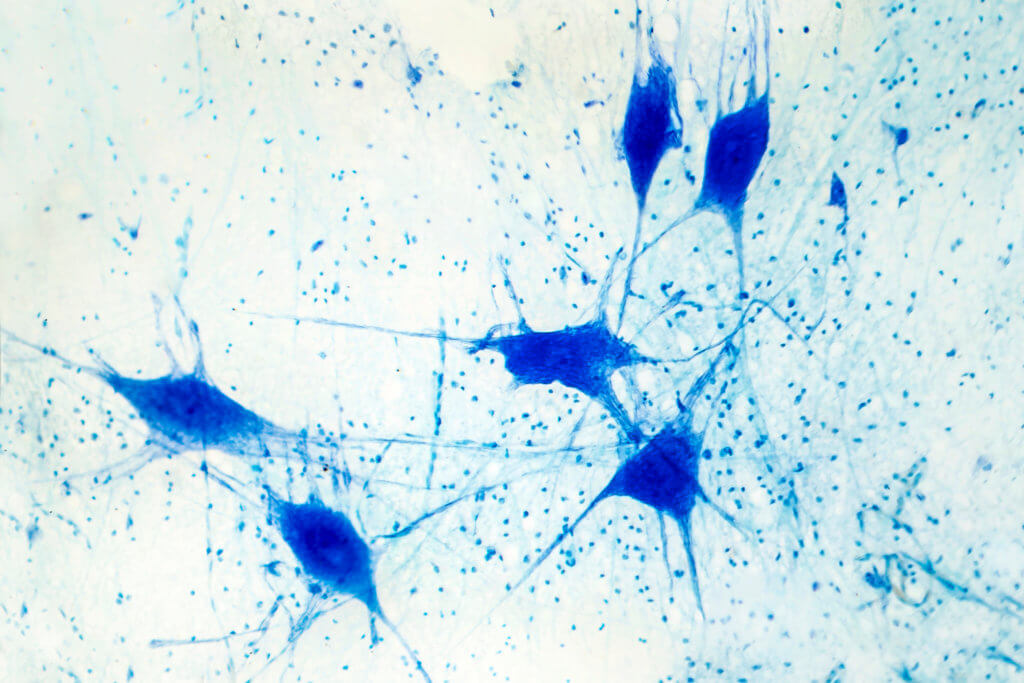

Brain organoids have been a game-changer in neuroscience research, allowing scientists to study the brain in ways that were previously impossible. These tiny, lab-grown structures mimic the cellular composition and organization of the human brain, providing valuable insights into how the brain develops and functions. Earlier this year, scientists successfully grew brain organoids, using human fetal tissue. This new development, termed fetal brain organoids or FeBOs, offers an unprecedented opportunity to study the intricate processes of early brain development. However, it also raises complex ethical and legal questions that demand careful consideration.

These questions are highlighted in a new paper by scientists from Hiroshima Univerity in Japan. The paper is published in the journal EMBO Reports.

Until now, most brain organoids were derived from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), which are cells that have the ability to develop into any type of cell in the body. While PSC-derived brain organoids have been instrumental in advancing our understanding of the brain, they have certain limitations.

“Our research seeks to illuminate previously often-overlooked ethical dilemmas and legal complexities that arise at the intersection of advanced organoid research and the use of fetal tissue, which is predominantly obtained through elective abortions,” says lead author of the paper Tsutomu Sawai, an associate professor at Hiroshima University, in a university release.

The FeBOs developed by Dutch and UK researchers offer a complementary approach to studying brain development. Unlike PSC-derived organoids, which typically reach a developmental endpoint, FeBOs can be established as long-term, self-renewing lines. This means that they can continue to grow and mature in the lab, providing a more accurate representation of the cellular characteristics of the native human brain tissue.

To create FeBOs, the researchers used human fetal tissue obtained from elective abortions at gestational weeks 12-15. The use of fetal tissue, particularly from abortions, is a highly sensitive and controversial topic. It raises a host of ethical concerns, including issues of informed consent, the potential for commercialization, and the public perception of such research.

One of the central ethical challenges surrounding FeBO research is the potential for these lab-grown structures to achieve consciousness. As FeBOs mature beyond the developmental stages of the original fetal tissues, they may approach the proposed ethical boundary in brain organoid research, which is equivalent to a 20-week-old human brain. This raises difficult questions about the moral status of FeBOs and the ethical implications of creating structures that may have some level of consciousness or sentience.

Another ethical quandary arises when considering the transplantation of FeBOs into animal models. Recent studies have shown that when brain organoids are transplanted into animals, they tend to mature further within the host brain. However, the consequences of this in vivo maturation, especially for FeBOs, are not yet fully understood. It is crucial to carefully examine the potential impact on both the organoids and the host animals.

The use of FeBOs also highlights the regulatory discrepancy between embryo and brain organoid research. The well-established ’14-day rule’ for human embryo research restricts in vitro cultivation to no more than 14 days after fertilization or until the appearance of the primitive streak, whichever comes first. However, generating FeBOs from 12-15-week-old fetal tissue raises significant ethical questions about the appropriateness of this rule and the need for increased dialogue to clarify the ethical boundaries of brain organoid versus embryonic research.

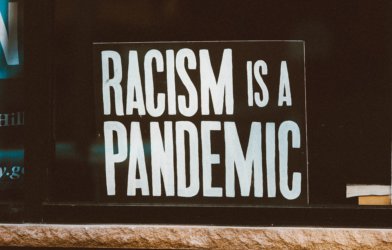

Adding to the complexity of the issue is the lack of comprehensive international regulation governing human fetal tissue research. The regulatory landscape varies widely across countries, shaped by distinct sociocultural, ethical, and legal paradigms. In the United States, for example, the use of human fetal tissue, especially from elective abortions, is closely tied to the polarizing debate on abortion rights. This has led to policy fluctuations under different administrations, with the current Biden administration maintaining stringent justifications and comprehensive procedural protocols for such research.

In contrast, the United Kingdom has been a pioneer in establishing guidelines for human foetal tissue research, with landmark frameworks like the Peel Code and the Polkinghorne Report emphasizing ethical dimensions, particularly regarding consent for tissue donation. These guidelines have had a profound influence on global standards, including those set by the International Society for Stem Cell Research (ISSCR).

The Netherlands, where the FeBO study was conducted, has a comprehensive regulatory framework for handling embryos and fetuses in research, outlined in the Fetal Tissue Act of 2001. This act provides specific guidelines for obtaining informed consent and permissible objectives for the storage and use of fetal tissues.

As the field of FeBO research expands, it is crucial to address the unique complexities and emerging ethical dilemmas it presents. The lack of comprehensive international and national regulatory frameworks specifically addressing FeBO research underscores the need for a sophisticated, globally coordinated approach. Funding agencies may also play a role in shaping the research landscape by restricting funding for countries with less stringent regulations.

The importance of the 14-day rule in countries like the UK and Japan highlights the need for in-depth national debates before any changes are made to accommodate fetal tissue research. However, relying solely on this measure may prove insufficient, as there is a risk of countries prematurely declaring themselves exempt from such regulations. This could potentially lead to the fragmentation of the international research community.

To navigate this complex landscape, the formulation of new, internationally accepted norms is critical. While challenging, it is essential to ensure that FeBO research progresses in an ethically responsible manner, balancing the immense scientific and medical potential with the need to address the profound ethical and legal implications.

The groundbreaking development of FeBOs marks a significant milestone in neuroscience research, offering unprecedented opportunities to unravel the mysteries of early brain development. However, it also brings to the forefront a web of ethical and legal challenges that demand careful consideration and robust dialogue among researchers, policymakers, and the public. As we stand at the threshold of this new era in neuroscience, it is imperative that we navigate this uncharted territory with wisdom, foresight, and a deep commitment to ethical principles.

-392x250.jpg)