An unprecedented 4D map of the human brain reveals the vital organ is much hotter than the rest of the body. The remarkable study shows the brain’s average temperature sits just above 101 degrees Fahrenheit, but can be even warmer, particularly in women during the daytime.

Such fluctuations could be a sign of good health and have implications for the treatment of head injuries, and even Alzheimer’s disease.

“To me, the most surprising finding is the healthy human brain can reach temperatures that would be diagnosed as fever anywhere else in the body,” says project leader Dr. John O’Neill, from the University of Cambridge University, in a statement. “Such high temperatures have been measured in people with brain injuries in the past, but had been assumed to result from the injury. We found that brain temperature drops at night before you go to sleep and rises during the day.

“There is good reason to believe this daily variation is associated with long-term brain health – something we hope to investigate next,” he adds.

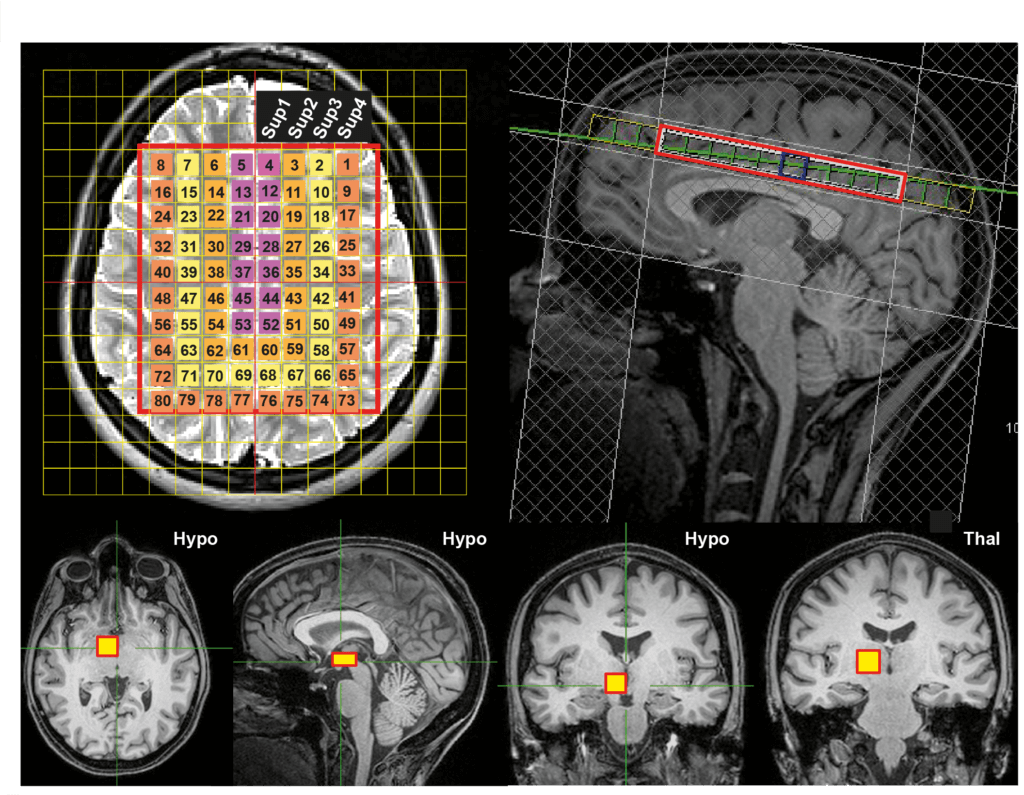

The first chart of its kind, named “HEATWAVE,” includes temperature. It was based on 40 healthy volunteers aged 20 to 40 years. They were scanned at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh over one day at three timepoints: 9 a.m., 4 p.m. and 11 p.m.

Participants were given a wrist-worn activity monitor, accounting for genetic and lifestyle differences in the timing of each person’s body clock, or circadian rhythm. It enabled identification of ‘morning larks’ or ‘night’ owls to be factored into the analysis.

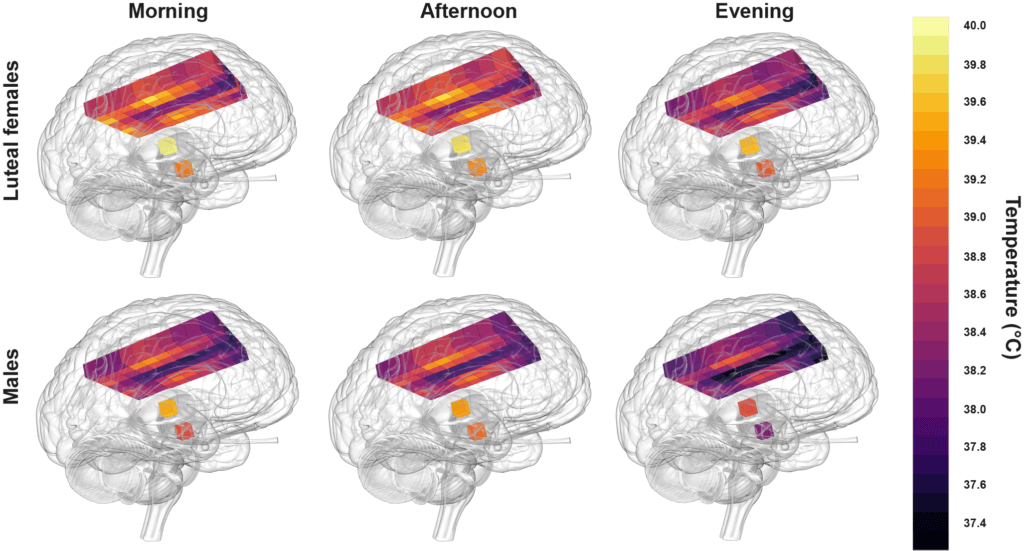

Average brain temperature was 101.3°F (38.5°C), warmer than the 98.6 standard when measured under the tongue. It also varied depending on time of day, brain region, sex and menstrual cycle and age. The surface was generally cooler.

But deeper brain structures were frequently warmer than 104°F (40°C), with the highest observed 105.62°F (40.9°C).

Across all individuals, brain temperature showed consistent time-of-day variation by nearly 1°C, with highest temperature observed in the afternoon, and the lowest at night. On average, the brains of females were around 0.4°C warmer than male counterparts — most likely driven by the menstrual cycle.

Most women were scanned in the post-ovulation phase when temperature was around 0.4°C warmer than that of others. The results also showed brain temperature went up over the 20-year age range of the participants — most notably in deep brain regions where the average rise was 0.6°C.

The brain’s capacity to cool down may deteriorate over time. Further work is needed to investigate if there is a link with dementia and other age-related brain disorders.

To explore the clinical implications, the researchers then analysed brain temperature data from 114 patients who had suffered moderate to severe head injuries.

The average was 101.3°F (38.5°C). But it varied even more widely — from 90.68 to 108.14°F (32.6 to 42.3°C). Only one-in-four had a daily rhythm in brain temperature. This was strongly linked with survival. Indeed, of these TBI (traumatic brain injury) patients, only four percent died in intensive care, compared to 27 percent of the rest.

Monitoring daily brain temperature cycles has potential as a tool for predicting prognosis, researchers say. The overall findings also raise important questions about the use of interventions to modify or control patient temperature in the clinic.

“Using the most comprehensive exploration to date of normal human brain temperature, we’ve established ‘HEATWAVE’ – a 4D temperature map of the brain,” says study leader Dr. Nina Rzechorzek, also from Cambridge. “This map provides an urgently-needed reference resource against which patient data can be compared, and could transform our understanding of how the brain works. That a daily brain temperature rhythm correlates so strongly with survival after TBI suggests round-the-clock brain temperature measurement holds great clinical value.

“Our work also opens a door for future research into whether disruption of daily brain temperature rhythms can be used as an early biomarker for several chronic brain disorders, including dementia,” she adds.

Previously, such studies have relied upon data capture from brain-injured patients in intensive care, where direct monitoring is often needed. More recently, a brain scanning technique called MRS (magnetic resonance spectroscopy), has enabled non-invasive measurements in healthy people.

But it had not been used to explore how brain temperature varies throughout the day or to consider how an individual’s ‘body clock’ influences this – until now.

The study, published in the journal Brain, was funded by the Medical Research Council.

Report by South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn