By now, it’s widely known that COVID-19 infection largely impacts respiratory health. But there’s much that still needs to be discovered through research. A new, small-scale National Institutes of Health (NIH) study reports that an immune response to COVID-19 infection can trigger brain damage. Though interestingly, they also found that SARS-CoV-2 wasn’t in the patient’s brains at all, which is consistent with previous studies.

So, how does the brain damage occur?

A research team from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) examined brain function in nine people who died abruptly after contracting the virus. Each individual was between the age of 24-73. They were chosen due to showing signs of blood vessel damage during brain scans.

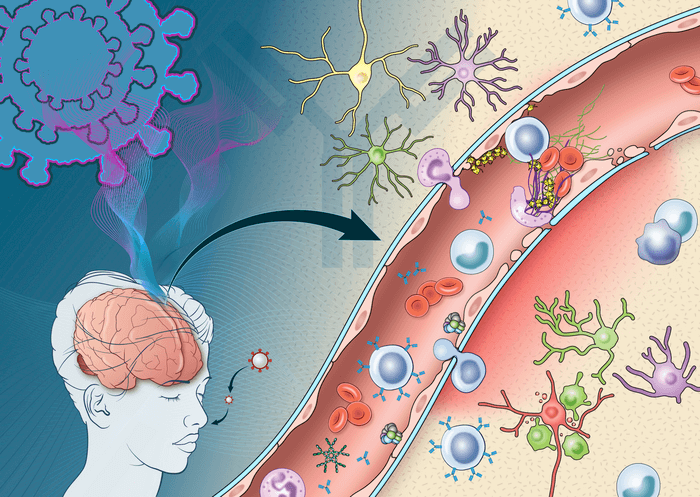

The team observed immune and neuroinflammatory responses through immunohistochemistry, a technique involving the use of antibodies to identify specific marker proteins within the brain tissue. Their evidence showed that this was specifically due to deposits of immune complexes, or molecules that bind to foreign substances in the body, forming on the surface of brain cells.

The observations suggest that the mechanism of action is an antibody-mediated attack on endothelial cells, the main regulators of inflammatory response. Once these cells are started up, they release adhesion molecules that cause platelets to stick to each other. Several of these molecules were found within the brain tissue of the COVID-19 patients.

“Activation of the endothelial cells brings platelets that stick to the blood vessel walls, causing clots to form and leakage to occur. At the same time the tight junctions between the endothelial cells get disrupted causing them to leak,” says Avindra Nath, M.D., clinical director at NINDS and the senior author of the study, in a statement. “Once leakage occurs, immune cells such as macrophages may come to repair the damage, setting up inflammation. This, in turn, causes damage to neurons.”

The other notable finding provides insight on a genetic level. It was found that in areas with damage to endothelial cells, over 300 genes had reduced expression while six genes had increased expression. The ones that saw an increase were associated with oxidative stress, metabolic dysfunction, and DNA damage. The researchers believe that this specific result may be key to enhancing clinical understanding of neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19 on a molecular level.

While small, this study provides a great baseline for greater research efforts that include more patients. It’s not common to suddenly die after contracting the virus, but it is certainly more likely that people develop long-term neurological symptoms like fatigue, headache, and loss of taste and smell. The researchers even agree that if the patients hadn’t passed, they’d likely have developed long COVID.

“It is quite possible that this same immune response persists in long COVID patients resulting in neuronal injury,” says Dr. Nath. This study provides scientists and researchers with the conclusion that treatments designed for preventing development of immune complexes may be crucial for COVID-related brain damage and other neurological issues.

This study is published in the journal Brain.