Although Alzheimer’s disease is widespread, no therapies exist, due to the difficulty of studying how the illness progresses. Scientists at the Salk Institute have now discovered new perspectives about what actually happens in Alzheimer’s patients by cultivating neurons that more closely mimic brain neurons in older individuals. The affected neurons, similar to the patients, seem to lose their biological identity.

Scientists say these neurons indicate signs of stress along with modifications in which the cells lack specialization, causing them to lose their identity. Many of the changes seen in these neurons are comparable to those seen in tumor cells, which is another illness associated with aging.

“We know the risk of Alzheimer’s increases exponentially with age, but due to an incomplete understanding of age-dependent pathogenesis, it’s been difficult to develop effective treatments,” says Professor and Salk President Rusty Gage, the paper’s senior author, in a statement. “Better models of the disease are vital for getting at the underlying drivers of this relationship.”

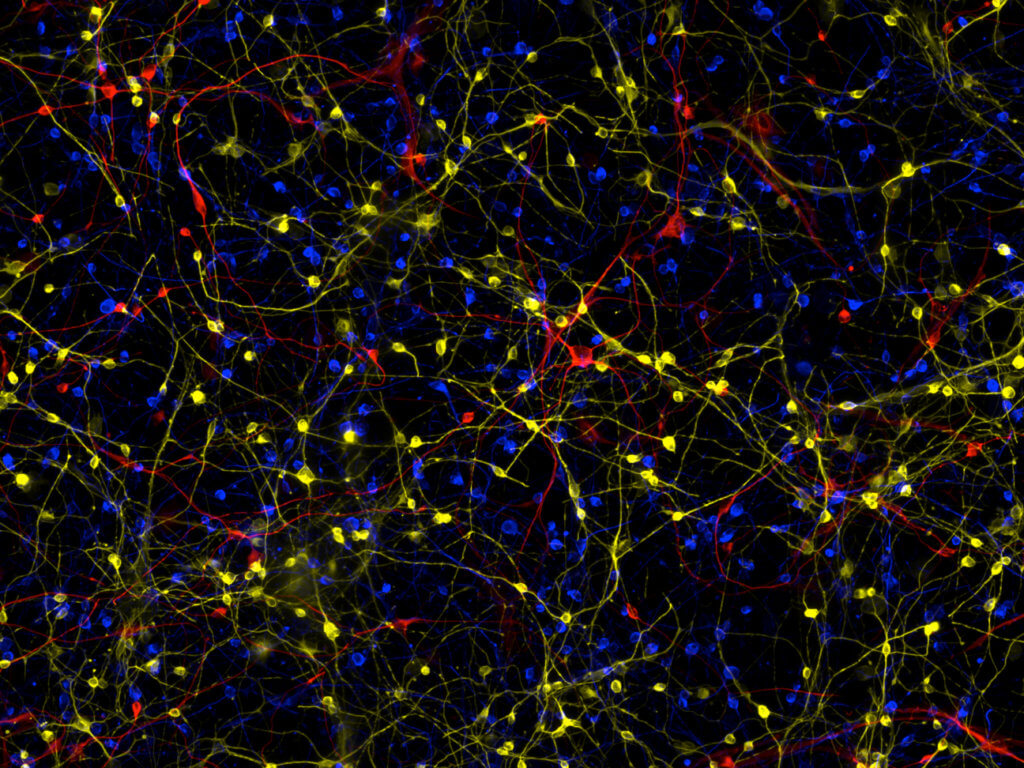

The Gage lab had previously demonstrated a unique method for creating brain cells using samples of skin. In other studies, pluripotent stem cells were used to produce specialized cells for testing, however, the generated neurons from the skin samples more precisely reflected the age of the individual from whom the cells came from. The current work expands on that discovery by being the first to utilize skin cells from Alzheimer’s patients to generate induced neurons with the same properties as the brain cells of those patients.

“The vast majority of Alzheimer’s cases occur sporadically and have no known genetic cause,” says Jerome Mertens, an assistant adjunct professor at Salk and first author of the paper, who was also involved in that earlier work. “Our goal here was to see if induced neurons that we generated from Alzheimer’s patients could teach us anything new about the changes that take place in these cells when the disease develops.”

For this study, researchers obtained skin cells from 13 individuals with irregular, age-related Alzheimer’s disease. Additionally, they utilized cells from three patients with the disease’s more uncommon, hereditary type. For the control group, they used skin cells from 19 individuals who were similar in age, but without Alzheimer’s disease. They created induced neurons from each participant’s cells using unique cells of the skin called fibroblasts. They next analyzed the molecular variations between Alzheimer’s patients’ cells and those that didn’t have the disease.

The researchers discovered that the generated neurons created from Alzheimer’s patients’ cells exhibited distinct features from the cells of healthy participants in the control group. The cells of Alzheimer’s patients lacked structures necessary for signal transmission, known as synaptic structures. Differences in their signal transduction pathways, which govern cell activity, also indicated stress within the cells.

Furthermore, the researchers discovered that the generated Alzheimer’s neurons showed extremely similar molecular fingerprints to immature nerve cells seen in the developing brain when they examined the cells’ transcriptomes—a specific study that indicates what proteins are being produced by the cells.

The neurons appeared to have forgotten their mature identities. This “de-differentiation”, whereby cells lose their specific features, has previously been reported in cancer cells. According to Mertens, who is also an assistant professor at the University of Innsbruck in Tyrol, Austria, this discovery opens the way for more research.

“While more research is needed, the changes associated with the transformation of these cells represent potential targets for therapeutics,” Gage adds.

The 2021 findings are published in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

Report by Amanda Christmas