The rapid eye movement (REM) phase of sleep evolved to help protect against predator attacks, according to recent research. Scientists say REM sleep ensures the brain’s stress threshold for waking up and fighting off attackers remains low.

Humans, as well as other mammals and birds, experience three to five periods of REM sleep a night, lasting generally for around 10 minutes each. These bring about brief, but periodic awakenings, described as a “sentinel function” to help animals prepare for fight or flight against predators.

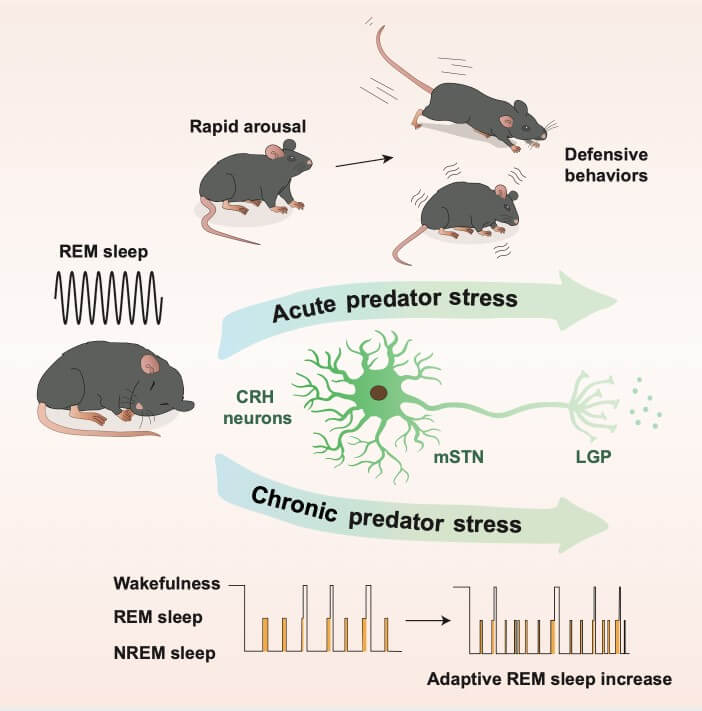

But there has not been any experimental evidence for this hypothesis until now, say researchers from the Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology (SIAT) in China. “The new findings in this study offer a potential evolutionary explanation of this phenomenon and elucidate the underlying neurobiological mechanism,” researchers explain in a media release. “The results also showed that sustained predator exposure induced a significant increase in total REM sleep time but shorter durations of individual REM-sleep episodes and sleep architecture fragmentation.”

Best Mattresses Of 2022: Top 4 Beds Most Frequently Recommended By Leading Experts

Animals sleeping in sealed containers were exposed to a substance called trimethylthiazoline (TMT) which mimics the strong smell of a predator.

“TMT triggered rapid arousal from REM sleep but not from non-rapid-eye-movement sleep. This suggests that REM sleep has specific properties that allow rapid arousal in response to predatory stimuli,” explains study co-author Dr. Liping Wang in the statement.

This was an interesting finding as it usually takes more to wake somebody from REM sleep than non-REM sleep. To take a closer look, the researchers studied part of the animal’s brain known as the medial subthalamic nucleus (mSTN). The mSTN contains a large number of neurons which release corticotropin, a hormone involved in the so-called stress response.

It took less to arouse these neurons during REM sleep so the animals could detect predators and defend themselves after awakening, the researchers explain. Animals continuously exposed to the smell of a predator enjoyed more REM sleep than others and it became more fragmented.

“We may hypothesize that natural selection favors optimizing existing neural circuitry for efficiency in signal transduction and energy usage over metabolically more expensive solutions,” says Wang.

An increase in REM-sleep has been linked to stress0related mood disorders in previous clinical studies. A potential evolutionary explanation of this phenomenon has now been discovered and its biological workings revealed.

“Our study raises the question of whether it is possible to treat mood disorders by targeting the common regulatory circuit of sleep and fear,” adds Wang. “We will continue working on this question.”

The findings are published in the journal Neuron.

Report by South West News Service writer Tom Campbell