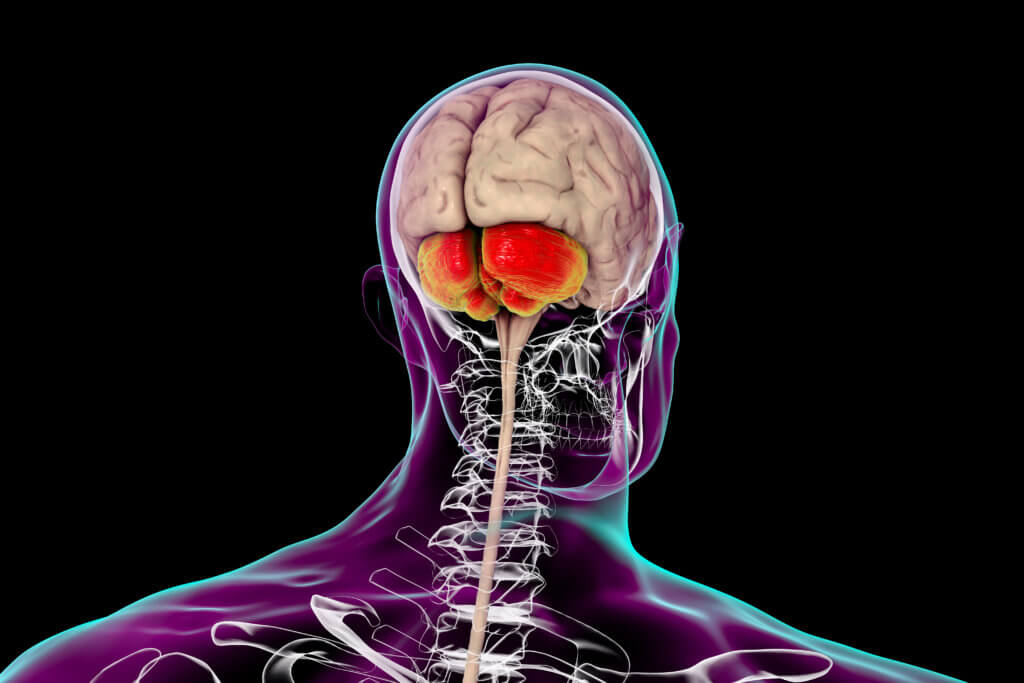

When we think about learning a new skill, like playing the piano or juggling, we usually focus on the role of the cerebrum — the large, wrinkled part of the brain that sits on top. But recent research suggests that the cerebellum, a smaller structure located at the back of the brain, may play a more important role in skill learning than previously thought.

In a new study published in Nature Communications, a team of neuroscientists from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Columbia University have uncovered a hidden conversation between the cerebrum and the cerebellum that’s critical for learning new visuomotor skills. Visuomotor skills involve coordinating visual information with motor actions, like hitting a baseball or typing on a keyboard.

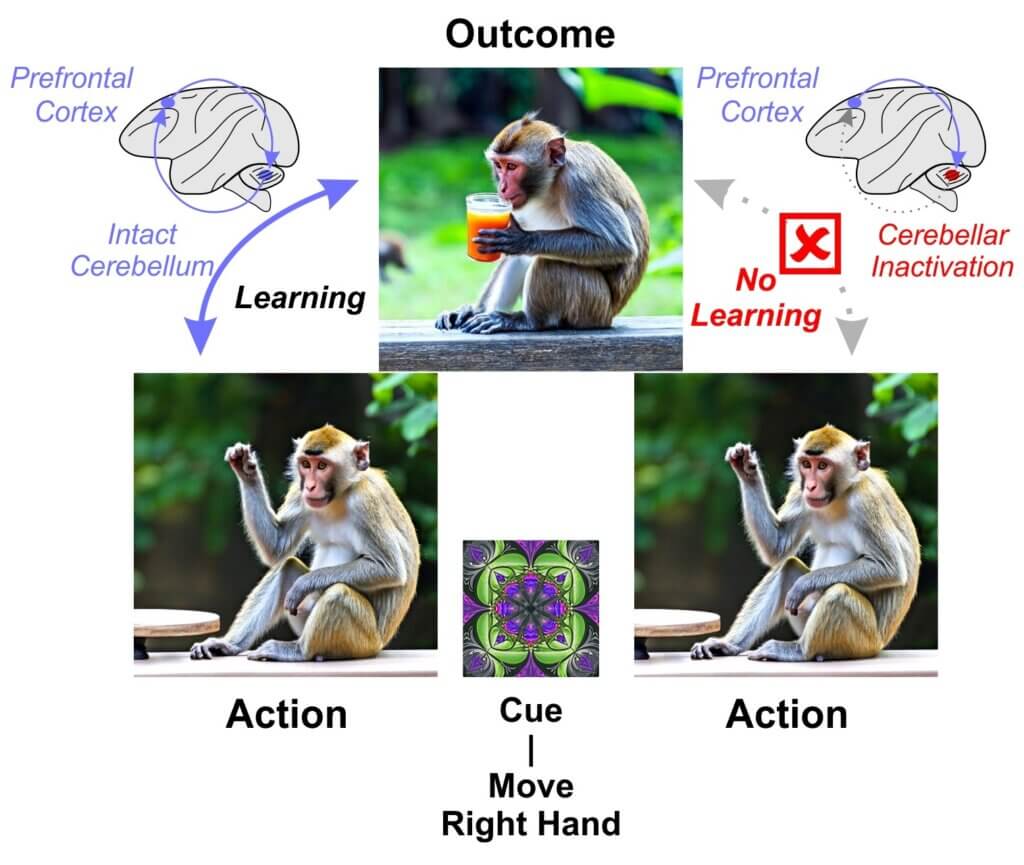

Researchers trained monkeys to learn a new visuomotor task, where they had to associate novel visual symbols with specific hand movements to receive a reward. As the monkeys learned, the scientists recorded activity in a part of their cerebellum called Crus I/II.

Neuroscientists were stunned after they found that when the monkeys made errors, certain cells in Crus I/II fired more, but as the monkeys learned the correct associations, this error-related activity decreased. This suggests that the cerebellum is keeping track of the monkey’s performance and sending feedback to help them learn from their mistakes.

“A longstanding assumption about cerebellar function has been that it only controls how we move. However, we now know that there are parts of the cerebellum that are connected and appear to have evolved along with areas of the cerebrum that control how we think,” says study co-author Dr. Andreea Bostan, research assistant professor in Pitt’s Department of Neurobiology, in a media release. “Because the cerebellum uses information about errors to gradually refine movement, another assumption has been that it likely contributes to cognitive functions in a similar way.”

To test whether this cerebellar activity was truly necessary for learning, researchers temporarily inactivated Crus I/II while the monkeys tried to learn new symbols. This disruption impaired the monkeys’ ability to learn, but had no effect on performing associations they had already mastered.

So what is the cerebellum communicating with to facilitate learning? Using a cutting-edge rabies virus tracing technique, the team mapped the brain-wide connections of Crus I/II and found that it forms a closed loop with a region of the frontal cortex called the PrePMd. The PrePMd is known to be involved in cognitive functions like learning arbitrary associations, so this connectivity suggests that the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex work together to help us acquire new visuomotor skills.

These findings overturn the classical view of the cerebellum as solely involved in fine motor control and introduce an exciting new role in higher-level learning. By tracking how well we’re doing and relaying that information to the prefrontal cortex, the cerebellum seems to act as a teacher, guiding the cerebrum to figure out the right answers.

This study is part of a growing body of work revealing that the cerebellum is more than just a motor control center. With its dense connectivity to the rest of the brain, including areas involved in cognition and emotion, the cerebellum seems to be a key information hub that helps coordinate our thoughts and actions.

“Our research provides clear evidence that the cerebellum is not only important for learning how to perform skillful actions, but also for learning which actions are most valuable in certain situations,” notes Dr. Bostan. “It helps explain some of the non-motor difficulties in people with cerebellar disorders.”

Understanding this brain-cerebellum dialog could have important implications for neurological conditions that involve cerebellar damage, like ataxia, autism, and schizophrenia. It may also inspire new approaches to neurorehabilitation and learning enhancement by targeting cerebellar circuits.