Most of us would probably never consider eating a cinnamon roll for lunch and call it a day unless it’s all we had. But maybe eating a turkey sandwich and following up with it sounds better? Craving something sweet after a meal is pretty common, but cravings for just about anything during pregnancy (or if you just don’t eat enough throughout the day) is even more common. Scientists can explain it through certain changes in our brain.

Our bodies generally need protein and fat to feel satisfied and push us through the day, but the little sweet treat after a meal can be a solid addition for the body’s fat stores in the average person. Some people might feel a stronger urge to consume their cravings depending on different factors. Largely, one might see a heightened desire if they have several nutrient deficiencies or are pregnant.

A new Portuguese study delves into how the brain handles these complex signals. “We show that the way the brain processes sensory input depends on whether animals lack specific nutrients or are pregnant”, says the study’s senior author Carlos Ribeiro, a principal investigator at the Champalimaud Foundation in Portugal, in a statement.

To conduct this work, Ribeiro’s team used fruit flies and focused on a not so well-studied area of the brain called the subesophageal zone (SEZ). It is thought to play an important role in making food choices.

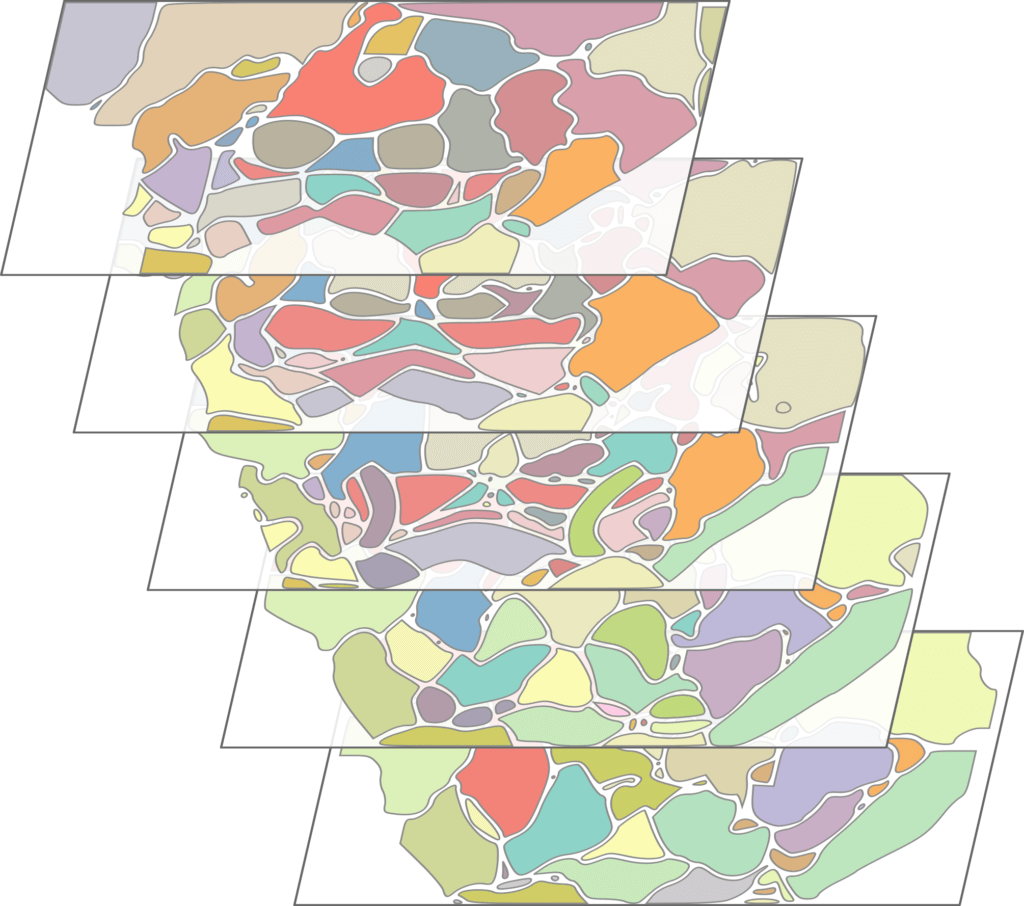

The team created a “functional atlas”, or a map of sort, of the SEZ in order to have a greater understanding of specific functions within the structure. Daniel Münch, the study’s lead author, first expressed a fluorescent activity reporter in all neurons in the fly brain. Then, he performed advanced 3D brain imaging in four groups of flies. “We wanted to understand how two powerful protein-appetite modulators — protein deprivation and reproductive status — interact in the brain. We, therefore, defined four experimental groups: fully-fed virgins, protein-deprived virgins, fully-fed mated flies, and protein-deprived mated flies,” Münch explains.

Their map was able to capture known regions, as well as completely unknown ones that showed lots of neural activity. They noticed that one area called the Borboleta region drives protein appetite, having an overwhelmingly strong effect across all groups. Oppositely, water and sucrose had next to no effect across the groups. Interestingly, protein-deprived and mated females had the most activity in the SEZ regions. This was an expected result according to the researchers, and showed that although protein deprivation and pregnancy are processed by the brain differently, they converge at the same area that detects protein appetite.

The fruit fly served as a thorough model for this research, according to the team. More importantly, their SEZ is similar to that of vertebrates. “It would be difficult to implement our approach in any other system than in fruit-flies. The tools we have nowadays make the fruit fly an amazing experimental system that enables us to dissect how the brain functions,” Münch concludes.

Study authors believe that their methods and results are promising for the neurology field, hopefully inspiring other scientists to use brain mapping to better understand specific brain activity and function.

The study is published in the journal Nature.