Anorexia and bulimia generally take the spotlight when you think of eating disorders, but binge eating disorder (BED) and the associated dangers are just as prevalent and important to control as the others. A new study conducted by University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine scientists shows that a small implanted device for high-frequency brain stimulation is a promising tool for aiding weight loss and reducing binge behavior.

Not only is BED just as prevalent as the more commonly-discussed disorders, it is actually the most common one in the United States. It generally is classified by feeling out of control around food, causing someone to eat far more than they need. This behavior also leads to excessive weight gain in most cases. Binge eating disorder is similar to bulimia in the sense that food is being eaten in great excess, but unlike it it isn’t accompanied by vomiting afterward.

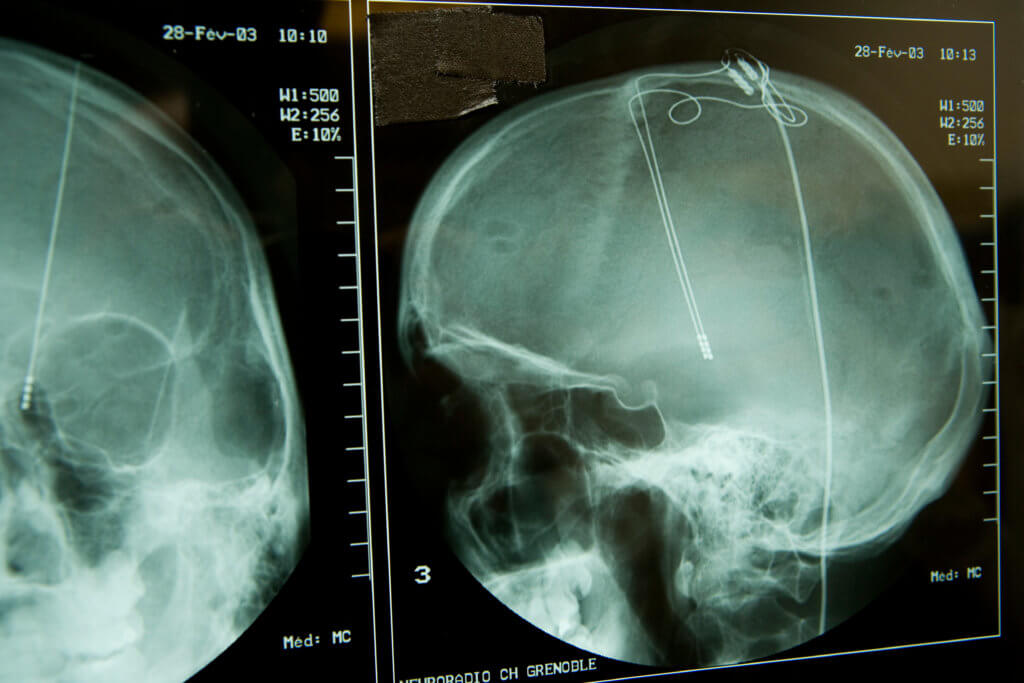

A 2018 study completed by the same team experimented on mice and people found that low-frequency electrical activity in the nucleus accumbens, the area of the brain responsible for eating, surfaces before a craving in binge eating, yet not regular eating. The researchers stimulated the area in mice to disturb the area, finding that the mice chose more calorically-appropriate foods than before when this happened.

Their new work uses the same device and methodology as the previous study, but in human subjects.

“This was an early feasibility study in which we were primarily assessing safety, but certainly the robust clinical benefits these patients reported to us are really impressive and exciting,” says study senior author Dr. Casey Halpern, an associate professor of neurosurgery and chief of stereotactic and functional neurosurgery at Penn Medicine, in a statement.

The researchers fitted two severely obese patients with binge eating disorder with devices, recording their brain signals for six months. The patients were sometimes put into situations like being in a buffet with their favorite foods — most commonly fast food and candy — but largely just were at home as normal. Researchers could film the patients’ binge eating moments in the lab, while at home the patients self-reported their habits. Results were ultimately consistent with their previous work.

In the next part, the devices delivered high-frequency electrical stimulation to the nucleus accumbens whenever the low-frequency signals related to cravings came about. During the six months, the patients reported feeling much less out of control with food, and also lost over 11 pounds. One subject was cleared and considered no longer as a BED patient. These results were astonishing, and did not come with side effects.

“This was a beautiful demonstration of how translational science can work in the best of cases,” says study co-lead author Dr. Camarin Rolle, a postdoctoral researcher with Halpern’s group,

Researchers have since continued following the subjects for six more months, and are recruiting more patients for a larger deep brain stimulation trial.

This study is published in the journal Nature Medicine.

-392x250.jpg)