For nearly three years, researchers have worked tirelessly to produce findings about COVID-19 infections and its immediate symptoms. Now, scientists are turning to study long-term impacts of the virus. In a recent study, researchers show that there is an increased risk of developing neurological conditions such as strokes, seizures, memory and movement disorders within the first year of infection.

The study was conducted by scientists from the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care system.

“We’re seeing brain problems in previously healthy individuals and those who have had mild infections,” says senior author Dr. Ziyad Al-Aly, a clinical epidemiologist at Washington University, in a statement.

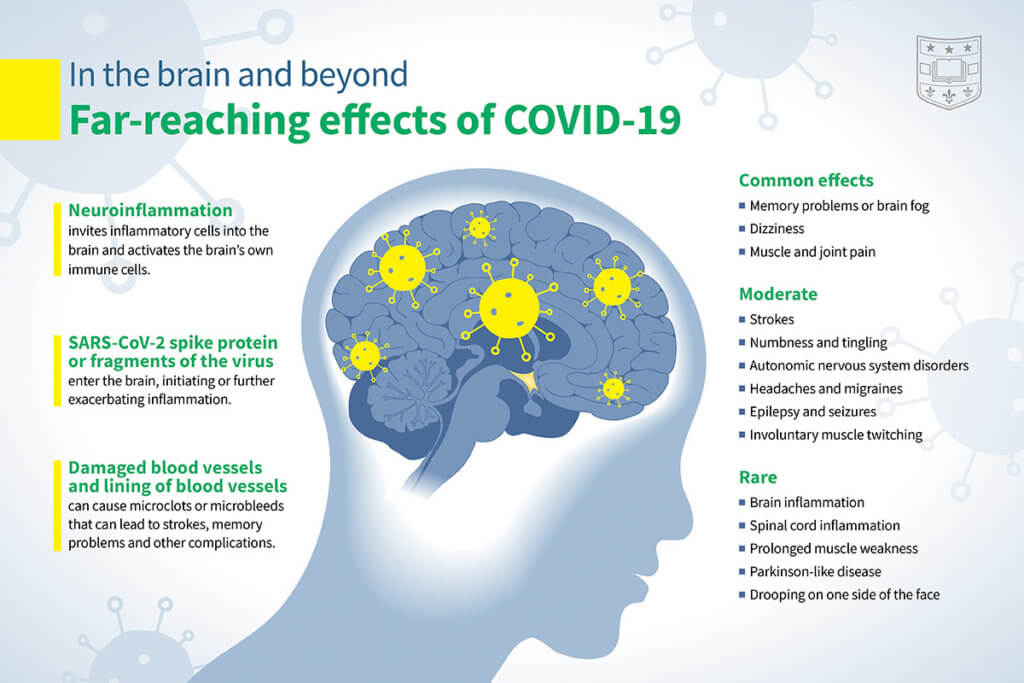

The virus has led to more than 40 million new cases of brain disorders around the world, study authors note. Previous works have only really looked at hospitalized patients, which doesn’t capture the best picture. In this study, the team evaluated neurologic disorders in both inpatient (including those in the intensive care unit) and outpatient setting.

They conducted the work using a controlled dataset from 154,000 people who had tested positive for COVID-19 sometime from March 1, 2020, through Jan. 15, 2021, and survived 30 days post-infection. Statistical modeling was used to analyze neurological outcomes in COVID-19 infection in comparison to a control group of over 5.6 million patients not infected with COVID-19 during the same time frame and also a control group of over 5.8 million people from March 2018 to December 31, 2019, prior to the pandemic entirely.

After monitoring brain health over a one-year span, the researchers found that incidences of neurologic disorders occurred in 7% more people with COVID-19 compared with those who hadn’t been infected at all. This translates to ~6.6 million people in the US who have experienced impaired brain function from the virus.

Memory loss and brain fog are some of the most common neurologic long-COVID symptoms. Compared with the control groups, people infected with COVID-19 had a 77% increased risk of developing memory problems. Additionally, people who contracted the virus were 50% more at risk of suffering from an ischemic stroke, 42% more likely to experience movement disorders (muscle contractions, tremors, etc.), and 80% more likely to develop epilepsy or seizures.

“These problems resolve in some people but persist in many others,” explains Al-Aly. “At this point, the proportion of people who get better versus those with long-lasting problems is unknown.”

Not to be forgotten is how infection has affected mental health in this patient population. Anxiety and depression are more likely to be experienced by 43%.

“Our study adds to this growing body of evidence by providing a comprehensive account of the neurologic consequences of COVID-19 one year after infection,” concludes Al-Aly. This study puts the pressure for governments and healthcare systems to develop sustainable policies that target prevention and improved health outcomes in people who have been infected.

This study is published in the journal Nature Medicine.