Ebola virus disease (EVD) is one of the deadliest infections known to humankind. After an infection appears cured, scientists reveal that the virus can hide in the brain, only to re-emerge, causing fatal disease or a deadly outbreak.

Recent EVD outbreaks in Africa have been linked to persistent infection in patients who survived previous outbreaks, according to the study’s senior author, Xiankun (Kevin) Zeng, PhD. Until now, the, the exact “hiding place” of persistent Ebola virus, and the mechanism of recurrence, were unknown.

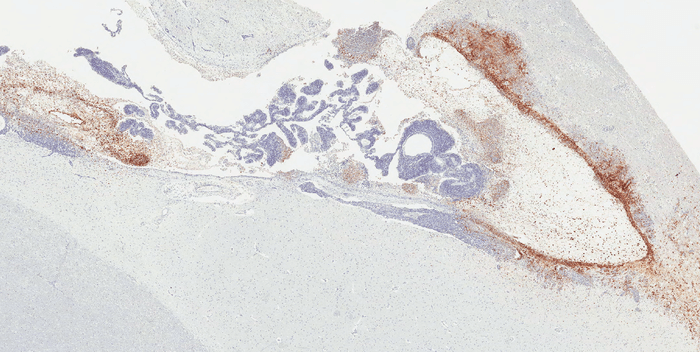

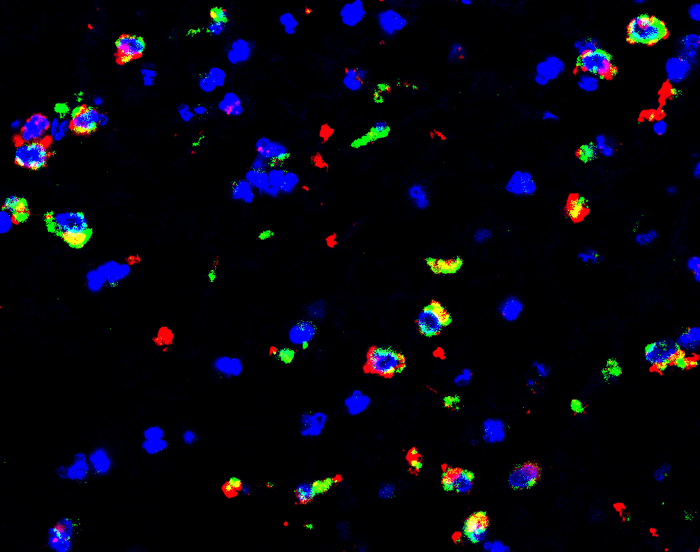

“Ours is the first study to reveal the hiding place of brain Ebola virus persistence in nonhuman primates,” Zeng said. “We found that about 20 percent of monkeys that survived lethal Ebola virus exposure after treatment with monoclonal antibody therapeutics still had persistent Ebola virus infection—specifically in the brain ventricular system, even when Ebola virus was cleared from all other organs,” he explained.

Systematic studies of Ebola virus persistence, performed by Zeng’s team at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases show that the virus can hide and persist. Specific regions of immune-privileged organs—such as the vitreous chamber of eyes, the seminiferous tubules of testes, and the ventricular system of the brain, harbor the virus until its re-emergence.

EVD is still a significant threat in Africa. According to the World Health Organization, there were three outbreaks in Africa in 2021. Re-emergence has been reported in human survivors of EVD.

The authors describe a case in which a British nurse experienced Ebola virus as meningoencephalitis, nine months after recovering from severe EVD. She had been treated with monoclonal antibodies during the 2013-2016 outbreak in West Africa, the largest outbreak to date.

In another case, a vaccinated patient who had been treated with monoclonal antibody therapeutics for EVD six months earlier relapsed. She died near the end of the 2018-2020 outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. That case generated many associated human-to-human transmissions.

Research in recent years has led to two vaccines and two monoclonal antibody therapies for prevention and treatment of EVD. The therapies are now standard care for infected patients.

“Fortunately, with these approved vaccines and monoclonal antibody therapeutics, we are in a much better position to contain outbreaks,” says Zeng. “Our study also reinforces the need for long-term follow-up of EVD survivors. He explains, “This will serve to reduce the risk of disease re-emergence, while also helping to prevent further stigmatization of patients.”

This study is published in Science Translational Medicine.