A new study at Harvard Medical School and Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health has revealed critical information underlying a type of dementia that strikes early in life. The findings may lead to the development of new therapies.

Dementia is not a disease. It applies to multiple diseases which are different types of problems with memory loss and failing thinking. It means that a part or parts of the body’s nervous system are deteriorating. Another important thing to know about dementias is that the diseases are harder on the loving caregivers of people with dementia than the diseases are on the people with dementia. I combed through dozens of so-called ‘inspirational’ quotes about dementia, but they seemed trivializing of the toll dementia takes on caregivers.

There is good news. The fields of medicine and social sciences have come a long way in providing care for caregivers. From the moment someone you love is diagnosed, let health and social science professionals help you establish support systems and take breaks from caregiving.

Diseases with dementia-type symptoms affect about 55 million people worldwide. There are few effective treatments, however, despite high-volume, intense research. Scientists still don’t fully understand how dementia arises in the cells and molecules of the brain and nervous system.

A breakthrough

Researchers discovered that a genetic form of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is associated with accumulation of specific lipids (fats) in the brain — the results of a protein deficiency that interferes with cell metabolism.

In addition, the findings highlight a mechanism of metabolic disruption that may be relevant to other diseases with dementia, the researchers reported, in a statement.

More about FTD

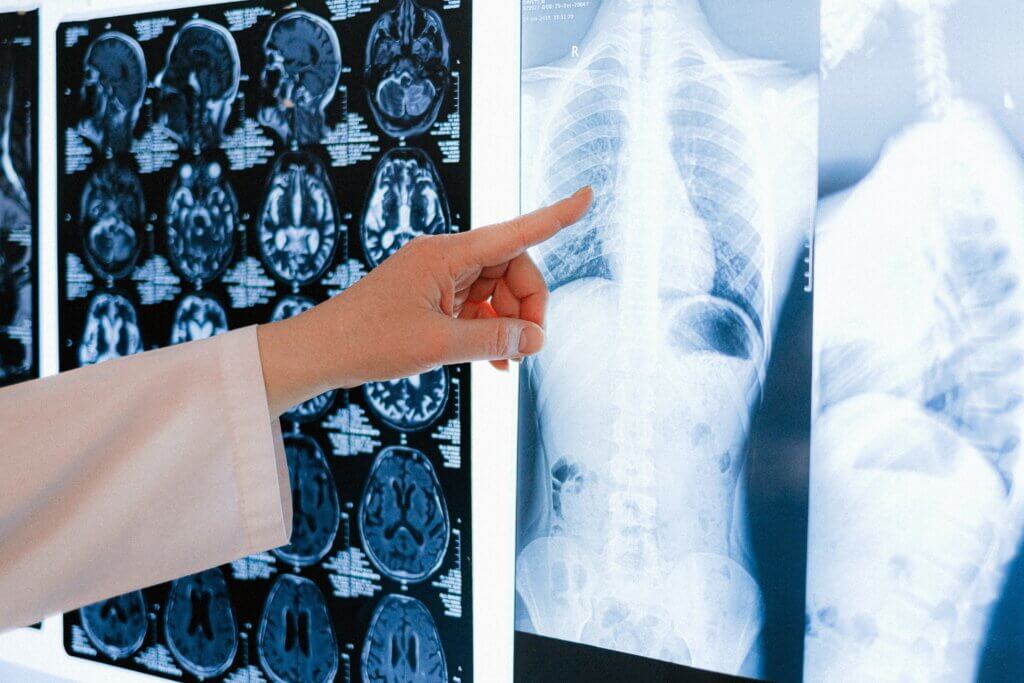

With FTD, there is a loss of cells in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. It accounts for 5 to 10 percent of cases of dementia. FTD is usually diagnosed between 45 and 65 years of age. A genetic form of FTD clusters in families. About 15 percent of the time, FTD is linked to a specific mutation in the GRN gene. It causes brain cells to stop making a protein called progranulin.

Other studies linked progranulin to parts of cells called lysosomes. These have roles in metabolic activities. Wade Harper, in the Department of Cell Biology at HMS, said, “The function of the protein, however, including its role in the lysosome, has remained sort of a black box.”

The researchers initially found that progranulin-deficient human cell lines and mouse brains, as well as brain cells from patients with FTD (collected post-mortem), had accumulations of gangliosides — lipids (fats) common throughout the nervous system.

The scientists found that lysosomes in these cells and tissues from brains with FTD had reduced levels of progranulin, and abnormally low levels of a lipid called BMP. BMP is required to break down lipids common to the central nervous system. When researchers added BMP to cells, however, these cells accumulated much lower levels of gangliosides.

Together, the findings suggest that progranulin in lysosomes helps maintain the BMP levels needed to prevent gangliosides from accumulating in brain cells — buildup that may contribute to FTD.

Potential new therapies

“People are already working on treatments that involve giving patients a source of progranulin, and our results are consistent with that approach potentially being therapeutically beneficial,” Walther added. It may be possible to develop therapies that replace BMP rather than progranulin, he said, targeting a different part of the mechanism. The researchers also think that a similar lysosome-based mechanism could be relevant for neurodegenerative diseases beyond FTD.

“The lysosome may be a key feature of many kinds of neurodegenerative diseases — but these diseases likely all connect with the lysosome in different ways,” Harper said.

“This study demonstrates the power of collaboration and following the science,” Walther said. “By using the right tools and asking the right detailed questions, you can sometimes uncover things that are unexpected.”

The study is published in Nature Communications.