Hereditary hemochromatosis is a disorder caused by a genetic mutation that leads the body to absorb iron in excess. This can cause complications like tissue damage, liver disease, and diabetes. Research suggests that the brain is protected from iron accumulation due to the blood-brain barrier, which generally protects against harmful pathogens and toxins. However, in a recent study, evidence of iron buildup in the brain was discovered.

The findings come from researchers at the University of California San Diego, along with teams from UC San Francisco, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Laureate Institute for Brain Research.

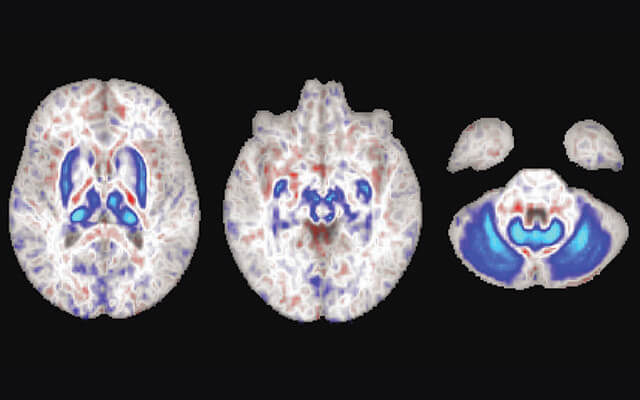

Scientists scanned the brains of 836 participants using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the research. About 20% (165) of them were in the high genetic risk group for developing hereditary hemochromatosis. The scans were able to detect iron deposits in the motor circuits of the brain for those that are high-risk. Researchers then analyzed data that represented close to 500,000 people, finding that males with the genetic risk for hemochromatosis were almost 2x more likely to develop movement disorders, like Parkinson’s disease.

Instead of just one genetic mutation commonly seen in those with this iron overload disorder, people with two copies of the gene mutation — one from each parent — show such a response with movement disorders. Their findings also suggest that males were at a much greater risk compared to females. This is consistent with their findings from the large-scale analysis.

“The sex-specific effect is consistent with other secondary disorders of hemochromatosis,” says first author Robert Loughnan, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in the Population Neuroscience and Genetics Lab at UCSD, in a statement. “Males show a higher disease burden than females due to natural processes, such as menstruation and childbirth that expel from the body excess iron build-up in women.”

Around 42 million Americans suffer from movement disorders, like Huntington’s disease and others. Each year, an estimated 60,000 Americans are diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease alone, and while most common in elderly populations, age of onset continues to decrease. Researchers believe that their findings support the need for more social and clinical awareness about iron accumulation in the brain.

“Screening high-risk individuals for early detection may be helpful in determining when to intervene to avoid more severe consequences,” says senior corresponding author Chun Chieh Fan, MD, PhD, an assistant adjunct professor at UCSD and principal investigator at the Laureate Institute for Brain Research.

This study is published in the journal JAMA Neurology.