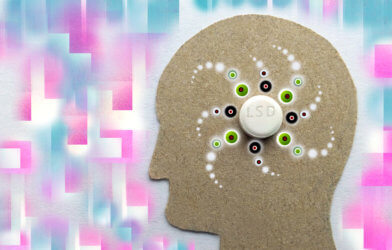

LSD. Acid. Lysergic acid diethylamide. Did anything good come to mind when you read those words? Few chemicals which are purported to be drugs have reputations as bad as that of LSD. Yet claims have been made that very small doses of the psychedelic, administered at regular intervals, can have favorable effects on a variety of medical conditions. New research at the University of Chicago, however, reports no evidence that such claims are valid.

Conditions about which claims have been made that LSD is an effective treatment include diseases such as fibromyalgia, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis, all associated with chronic pain. Some researchers claim that LSD is useful in other inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, and several mental illnesses, including depression and anxiety .

“These drugs are already being used out in the world, and it’s important for us to test them under controlled conditions, ensure their safety and see whether there’s some validity to the benefits people claim. That’s something that has been missing from the conversation,” says Harriet de Wit, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at UChicago, in a statement.

De Wit and colleagues studied the effects of four repeated low doses of LSD, administered under lab conditions every three to four days. One group of participants received 13 micrograms of the drug, a second group received 26 micrograms, and the third received a placebo. (100-200 micrograms is the common dose for getting high.)

The drugs were given to participants at supervised laboratory sessions, with a follow-up session three to four days after the last dose. They were not told what kind of drug was being tested in the study. “Because in the real world, people’s expectations can strongly influence their responses,” explains Wit.

Participants completed cognitive and emotional tasks both during the drug administration sessions and at the drug-free, follow-up session. Some participants who received the higher dose of LSD reported feeling a modest “high” during the drug sessions.

LSD microdoses did not improve mood or affect participants’ performance on cognitive tests, either during the drug sessions or at the follow-up session.

De Wit says the results were a disappointing surprise. “Because so many people claim to have experienced benefits from microdosing, we expected to document some kind of beneficial effect under laboratory conditions,” she said.

There were also neurobiological reasons to expect that LSD might improve mood. LSD acts through serotonin receptors, where some common antidepressants are active.

“We can’t say necessarily that microdosing doesn’t work,” de Wit says. “All we can say is that, under these controlled circumstances, with this kind of participant, these doses, and these intervals, we didn’t see a robust effect.”

She also notes that outside the laboratory, people who microdose often have strong expectations of beneficial effects. “It is possible that these expectations contribute to the apparent benefits or they may interact with the pharmacological effect of the drug,” she says.

According to the scientists, the study did confirm that microdosing LSD is safe. Previous studies have not found LSD to be toxic, even at high doses. Researchers measured participants’ heart rate, blood pressure, other vital signs and impairment. They did not document any negative effects.

Participants appeared to build a tolerance to LSD over the course of the study, with the strongest “high” reported at the first session but diminishing with each session.

“There are a lot of companies getting into the drug business, either with psychedelic drugs, or drugs like cannabidiol,” de Wit noted. “And really there’s not very much empirical support to back up their claims. So, I think we have a responsibility to investigate and validate the claims.”

The study is published in the journal Addiction Biology.

-392x250.jpg)

Comments