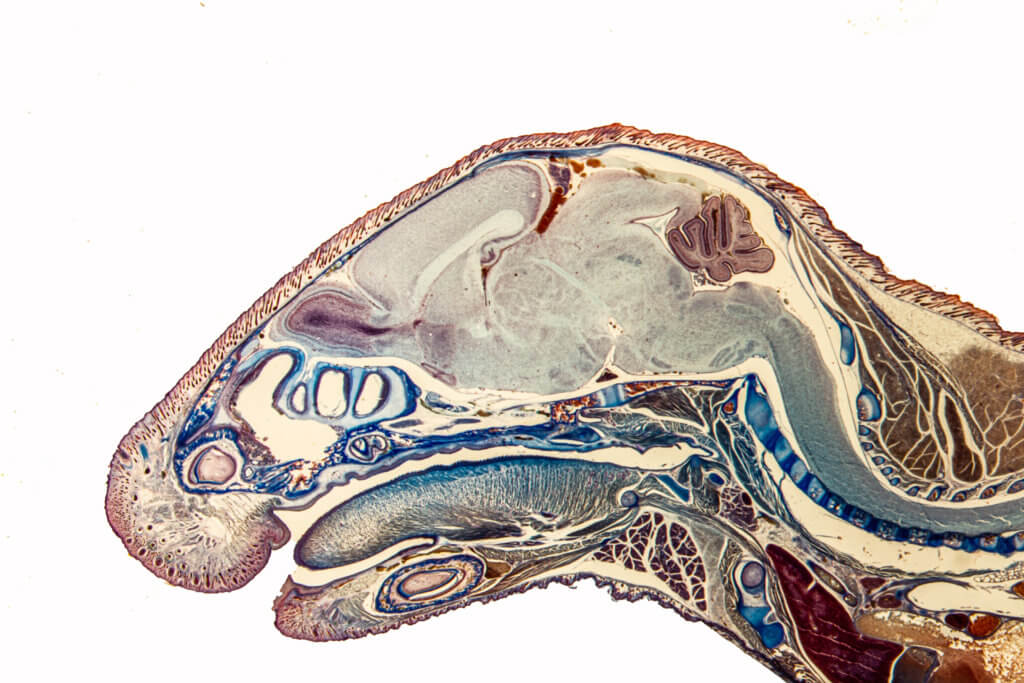

Scientists recently discovered more than 1000 genes that are significantly more active in the brain of female mice compared to male mice. Analyzing tissue from brain structures of both males and females, researchers uncovered that certain cells are responsible for activating sex hormones. Several structures within the brains of these mice were examined, including four areas known to impact “rating, dating, mating and hating” behaviors.

The study authors believe the findings likely carry over into humans as well, as brain cells in mice are analogous to those in other mammals, including humans.

Researchers from The Stanford University School of Medicine, in collaboration with Accent Therapeutics and Columbia University, contributed to the study. Stanford School of Medicine professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and neurobiology, Nirao Shah, PhD. was a senior author of the study. Shah and his team identified specific groups of cells in the brain that are responsible for activating specific sex-specific behaviors.

The study uncovered more than 600 differences specific to female mice where gene-activation levels varied in different phases of their estrous cycle. Although female mice do not menstruate, the estrous cycle is equivalent to the menstrual cycle in women.

“To find, within these four tiny brain structures, several hundred genes whose activity levels depend only on the female’s cycle stage was completely surprising,” Shah remarks in a media release. “Mice aren’t humans, but it’s reasonable to expect that analogous brain cell types will be shown to play roles in our sex-typical social behaviors,” he said.

The study primarily focused on the brains of male and female mice and their reproductive behaviors, however, additional insight regarding sex-specific brain disorders were also uncovered. In their research, Shah’s team found that there are 29 genes more active in males than females and 10 genes more active in females compared to males. These findings are significant as past research has identified 207 genes that are believed to be linked to the autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Moreover, ASD is four times more commonly diagnosed in men than women.

Certain social behaviors were observed in both male mice and female mice that date back millions of years as a result of evolution. When male mice encountered other mice on their turf, they responded differently depending on the sex of the other mouse. If male, they perceived the other male mouse as an intruder and attacked it. If female, they pursued the stranger and had an intimate exchange.

Additional observations were made regarding the female mice’s maternal instincts. The female mice vehemently protected their pups from any perceived threat, wanting to attack anything that appeared to cause harm. They retrieved the ones who strayed and generally cared more about their offspring.

The team’s findings were remarkable, given the cell’s obscurity in the brain. Shah likens the search for the cells similar to finding a needle in a haystack. “The cells we identified as mission-critical for these sex-typical rating, dating, mating or hating behavioral displays account for probably less than 0.0005% of all the cells in a mouse’s brain,” he says.

Scientists further examined how the cells might be impacted when they were taken from their surroundings and observed for genetic content, on a cell-by-cell basis. Researchers were able to identify crucial cells that responded to estrogen. This hormone, along with progesterone, may be measured at different levels throughout a woman’s cycle, and corresponding sex-type behaviors correlate to the variation in hormones. In mice, ovulation is known as the estrous stage. Both hormones are at their peak level when this occurs. The opposite is true for the diestrus stage when hormone levels are at their lowest.

Shah and his team were able to pull tissue from each of the four brain structures and purify it in a way that populated estrogen-responsive cells. Researchers found 1415 genes with different activity levels among the group. They observed many differences in the estrogen-responsive cells.

The bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), also found in the human brain, contained 36 separate cell types that were especially active among the mice groups. Of the 36 estrogen-responsive cells, researchers were able to pinpoint one of them and identify it as essential to male mice’s ability to recognize the sex of a stranger mouse.

Researchers observed another brain structure, the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), which is also found in the human brain. Twenty-seven estrogen-responsive cell types were distinguished. Scientists found when one of those cell types was removed, it transformed the behavior of females who would normally respond to sexual advances but did not, even when they were at the peak of their cycles. This was not the case for the other 26 cell types.

The “needles within the needles” within the haystack that is the brain is a place of unchartered territory. Shah and his team were able to identify BNST and VMH cell types that impact males’ ability to recognize gender and females’ receptivity to sexual advances, however much is yet to be uncovered. There are 35 additional sex-hormone-responsive BNST cell types and 26 equivalents in VMH that have yet to be observed.

“This is probably just the tip of the iceberg. There’s likely to be many more sex-differentiated features to be found in these and other brain structures, if you know how to look for them,” Shah concludes.

Findings from this study are published in the journal Cell.