Witnessing a beautiful view or just cuddling next to someone we care about can bring on all the good, cozy feelings. Japanese scientists from Osaka University have been curious about what that looks like inside our brains. To that end, they launched a study that successfully generated a light sensor to see the process of oxytocin (also known as the “love drug”) release.

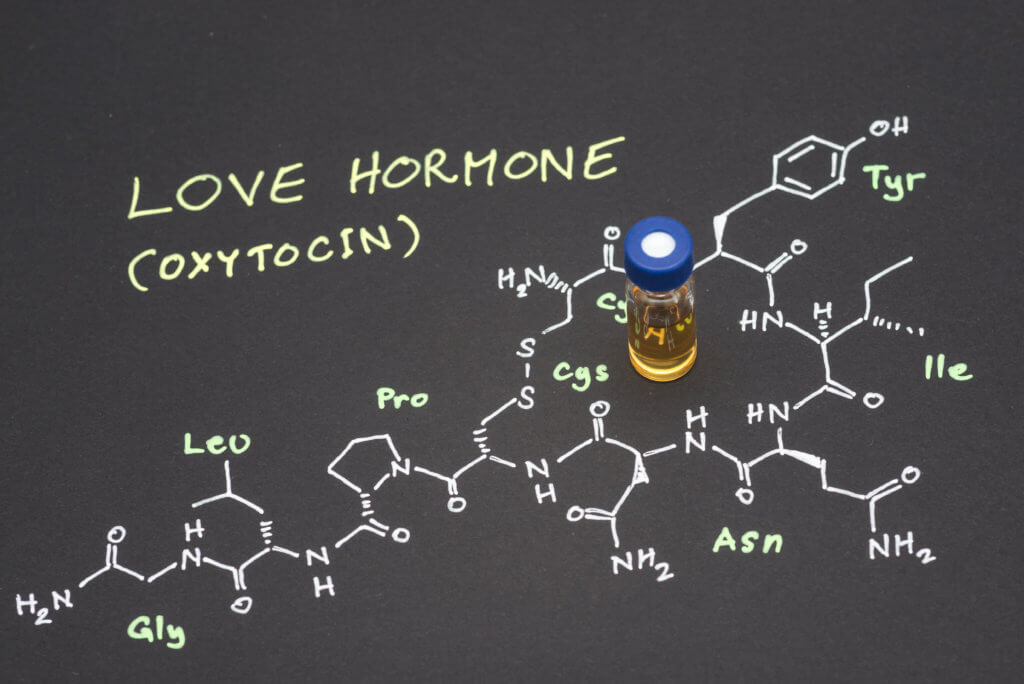

Oxytocin is involved in several aspects of what we consider normal human experiences like aging, childbirth, appetite, and general emotions. It’s in charge of giving us feelings of love, happiness, and warmth. When signaling of this hormone is weakened, it tends to show itself through disorders like autism and schizophrenia, and even in more common circumstances like low libido, social isolation, and menopause complications.

Previous experiments aimed to accurately detect and monitor oxytocin patterns haven’t quite been able to capture how the hormone changes over time. Therefore, this research team chose to pursue the task of engineering a tool that can achieve this with precision.

“Using the oxytocin receptor from the medaka fish as a scaffold, we engineered a highly specific, ultrasensitive green fluorescent oxytocin sensor called MTRIAOT,” says lead author of the study, Daisuke Ino, in a statement. “Binding of extracellular oxytocin leads to an increase in fluorescence intensity of MTRIAOT, allowing us to monitor extracellular oxytocin levels in real time.”

To understand how well their technology works, the team conducted several cell culture analyses. “We examined the effects of potential factors that may affect oxytocin dynamics, including social interaction, anesthesia, feeding, and aging,” says Ino.

Their analyses show various changes in oxytocin behavior, dependent upon behavioral and physical situations the animals experienced. Oxytocin was observed to be at different levels according social interaction, anesthesia, feeding patterns (such as food deprivation), and aging as the team hypothesized.

Their findings suggest that MTRIAOT may greatly aid efforts to closing gaps in knowledge that neurology researchers have regarding oxytocin brain patterns. Because deviations from normal oxytocin signaling tends to relate to developmental and mental illness, such an advancement may help mount evidence for new therapies that can help people have more positive outlooks and be happier.

This will be beneficial as neurologists continue to struggle with personalized mental health care and less than desirable SSRI success rates. Additionally, the researchers explained that that the backbone of their sensor could be used as a base for additional sensor creation generated for other hormones and even neurotransmitters.

This study is published in the journal Nature Methods.