Scientists have identified the previously elusive starting points in the nervous system pathways from pleasurable social touch to the brain. For the first time, using mice, they mapped out the full length of the pathways that begin in the skin, destined to for the pleasure centers in the brain.

These starting-point nerve sites may open doors to therapies based on touch. Many people with autism are repulsed by even gentle touch. It will be exciting to work on touch therapies using this new finding to relieve a debilitating, isolating symptom of autism. Other conditions to be studied for their responses to touch therapy include anxiety, depression, and stress.

Mapping skin-to-brain pathways

“We set out to test whether there might be tactile neurons specifically tuned for rewarding touch,” says Dr. Ishmail Abdus-Saboor, an assistant professor of biological sciences at Columbia University, in a statement.

“We saw that by activating this understudied population of tactile sensory cells in the mouse’s back that the animals would lower their backs and take on this posture of dorsiflexion,” said Dr. Leah Elias, a graduate student at the time of the study, and now a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. In the world of rodents, such a posture is a key signature of sexual receptivity, which normally requires the physical attentions of a suitor mouse.

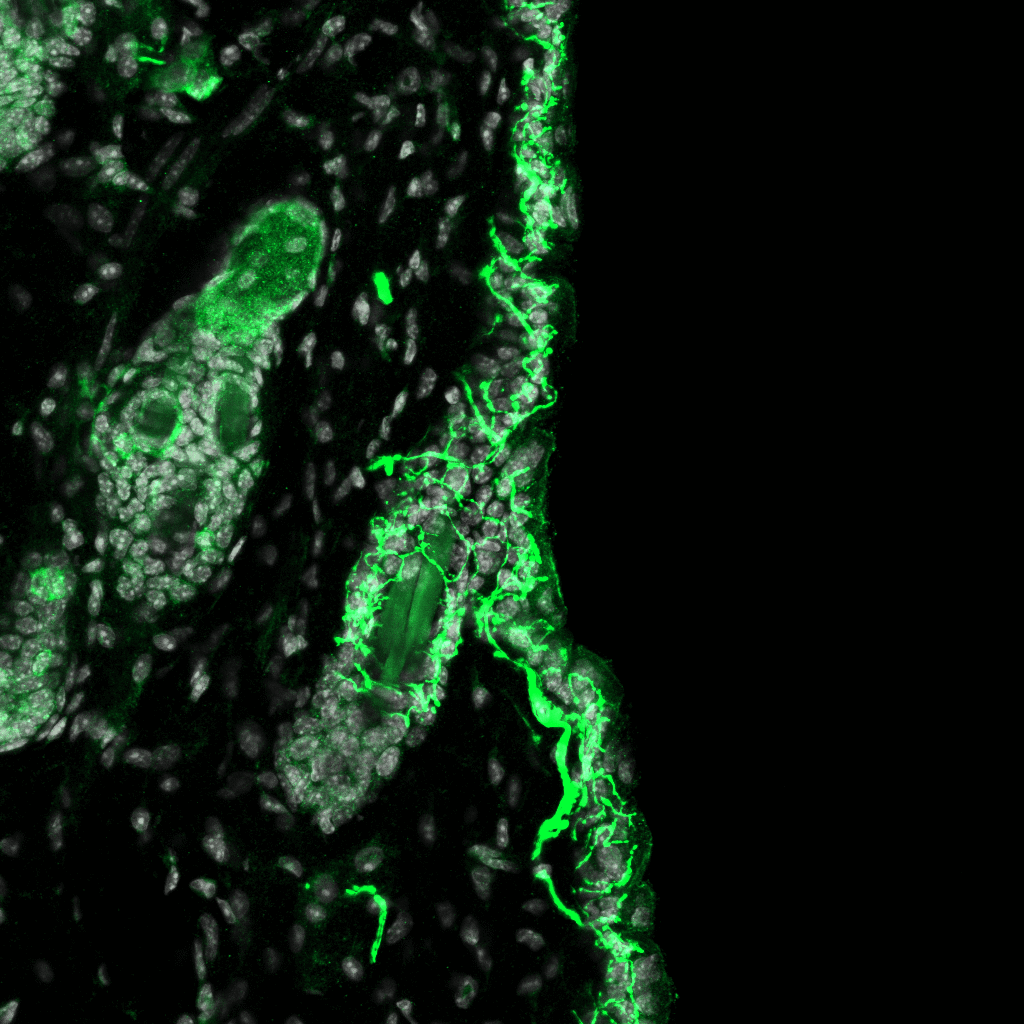

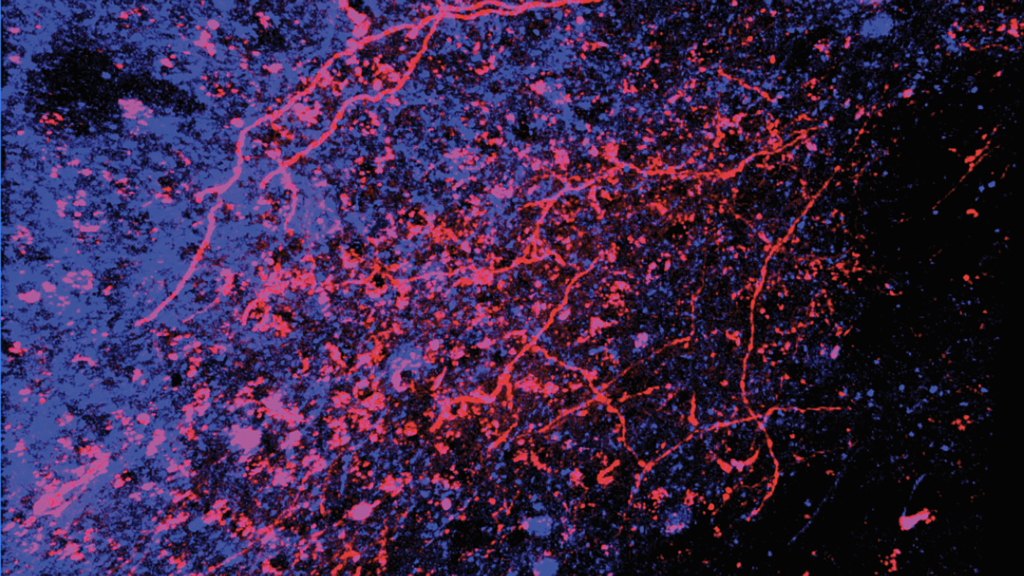

The team genetically engineered mice so that their touch-sensitive cells responded to stimulation with blue light. Activating these cells induced a sexual response from the mice, and activity in the nucleus accumbens, a reward center in the brain.

Withdrawal of the light stimulation curtailed the response. “The sexual receptivity just plummeted,” Dr. Elias adds. “We then knew for sure that these cells were important for social touch in natural encounters.”

Sensory pathways point to new therapies

Humans have neurons in the spinal cord and brain neurons that correspond to the sensory cells in the mice. These similarities may indicate neural pathways for potential biomedical applications. According to Dr. Elias, it may be possible to develop touch therapies, or drugs applied to the skin, for treating stress, anxiety or depression.

“A cardinal symptom for many people with autism is that they do not like to be touched,” Dr. Abdus-Saboor notes. “This begs the question of whether the pathway we’ve identified could be altered so people can benefit from touch that would normally be rewarding, rather than aversive.”

Learning from the pandemic fallout

“The pandemic made us all acutely aware of how devastating the lack of social and physical contact can be,” Dr. Elias says. “I think about the mental decline of the elderly in nursing homes who could not have typical contact with visitors. I think about how physical contact between parents and their newborns and young children is necessary for proper cognitive and social development. We don’t yet understand how these kinds of touch convey their benefits, whether acutely pleasurable or promoting long-term mental wellbeing. That’s why this work is so essential.”

This research is published in Cell.

-392x250.jpg)