Turns out many adults may not be smarter than a fifth grader. Kids and adults have different brain messaging signals that affect how quickly they pick up on new material. That’s according to a new study that examined visual learning in elementary schoolers and adults using behavioral and advanced neuroimaging techniques. Researchers have found that these differences lie in GABA, a neurotransmitter critical to stabilizing learning.

So far, children being stronger learners than adults has been an accepted notion despite limited evidence to support it. “It is often assumed that children learn more efficiently than adults, although the scientific support for this assumption has, at best, been weak, and, if it is true, the neuronal mechanisms responsible for more efficient learning in children are unclear,” says Takeo Watanabe of Brown University, in a media release.

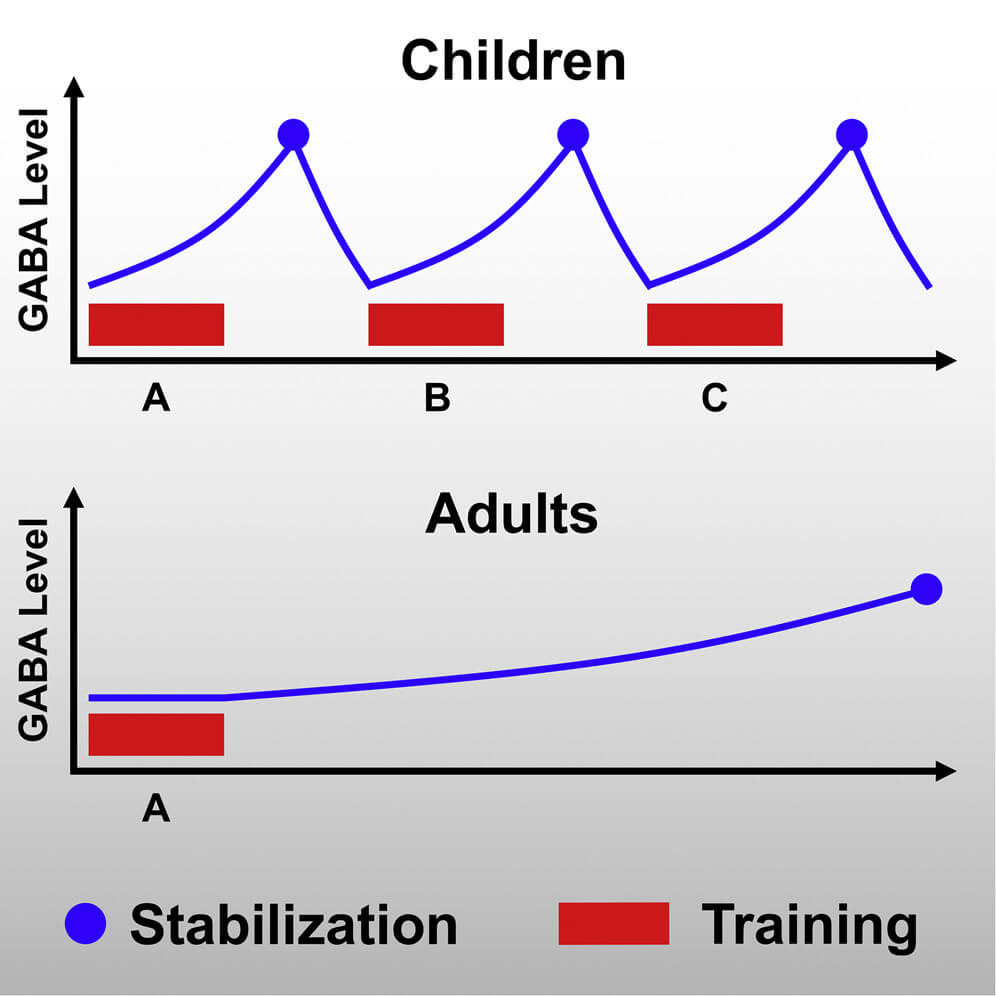

GABA has already been a focus in much of the research on this topic. Even so, the team noted that GABA in kids had only been measured at one point in time. It also hasn’t ever been measured at a time of specific significance for learning. To explore things in more depth, they investigated how GABA levels change before, during, and after learning.

In doing so, they discovered that visual learning triggered a boost in children’s GABA levels within their visual cortex, which processes visual information. These levels remained heightened even after the training ended. Among the adults, the responses weren’t as strong. There were no effects seen in GABA at all, suggesting that new material training can quickly increase the concentration of GABA in children, leading to more stabilized learning.

Additional experiments implied this even more.

“In subsequent behavioral experiments, we found that children indeed stabilized new learning much more rapidly than adults, which agrees with the common belief that children outperform adults in their learning abilities,” says Sebastian M. Frank, now at the University of Regensburg, Germany. “Our results therefore point to GABA as a key player in making learning efficient in children.”

The team agrees that these results should encourage educators and parents to provide children with opportunities to learn new skills, even if it’s just riding a bike or learning simple math. This work also has the potential to change how neuroscientists view brain maturation in kids, especially with regards to visual learning. The researchers note that differences in maturation rates between brain regions and functions should be the focus of studies to come. Further, they hope to investigate GABA responses across other learning methods, such as reading and writing.

The findings are published in the journal Current Biology.