The beyond-phantasmagoric images of current technology have birthed an emerging field of research called second-person neuroscience. Researchers at Keio University in Japan are refining the new field’s technique, called hyperscanning – the simultaneous recording of the activity of multiple brains.

Cooperative society seems to be disintegrating. Can it be salvaged? Do we dare think we can achieve a more cooperative, more noble social structure than ever before? It won’t happen studying one brain at a time. With hyperscanning, scientists can monitor the brains of people as they interact.

Hyperscanning started with the use of near-infrared spectroscopy to analyze brain synchronization between individuals performing motor tasks. The recordings, though, may just have been showing simultaneous motor behaviors.

Now, hyperscanning studies can reveal nonstructured communication and creative intent. Still, however, the technique needs to allow the extraction of social behaviors on video and link them to brain synchronization patterns. Also, analysis is limited to just short-term social interactions.

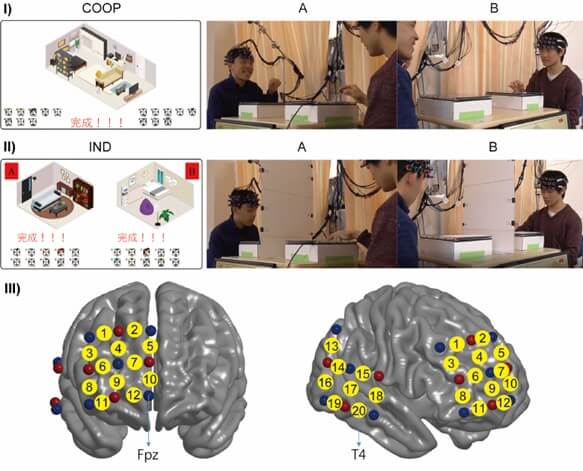

The research team, led by Yasuyo Minagawa has presented a possible solution to the technique’s limitations. With computer vision techniques to extract social behaviors from a two-participant task, they used a linear model to link social behaviors to neuronal synchrony, both between brains and within each participant’s brain.

Study participants were paired and tasked with furnishing a digital room in a computer game, freely communicating their preferences. They also completed the same task alone, yielding both between-brain synchronizations (BBSs) and within-brain synchronizations (WBSs) during the individual and cooperative tasks. The team focused on whether the participants directed their gaze at the other’s face.

During cooperative play, there was a strong BBS among the superior and middle temporal regions and specific parts of the prefrontal cortex in the right hemisphere, but little WBS in comparison. The BBS synchronization was strongest when one of the participants raised their gaze to look at the other.

Minagawa describes the synchronization as a “two-in-one system” during certain social interactions. “Neuron populations within one brain were activated simultaneously with similar neuron populations in the other brain when the participants cooperated to complete the task, as if the two brains functioned together as a single system for creative problem-solving,” she explains in a statement. “These phenomena are consistent with the notion of a ‘we-mode,’ in which interacting agents share their minds in a collective fashion and facilitate interaction by accelerating access to the other’s cognition.”

This study yields evidence that human brains can understand and synchronize with each other to manage tasks. Minagawa said, “We could apply our method to more detailed social behaviors in future analyses, such as facial expressions and verbal communication. Our analytical approach can provide insights and avenues for future research in interactive social neuroscience,” she concluded.

The study was published in Neurophotonics.