Doctors typically use the process of elimination to rule out specific conditions when making a diagnosis. Research shows that strategy can be applied to everyday life. According to a recent study, the brain can recognize when you need a better approach to solving a problem. Scientists say when a person has difficulty solving a puzzle or deciphering a pattern, the brain will quickly start over to develop a new strategy.

For the study, 200 participants attempted to decipher puzzles as a computer scanned their brains using functional MRI (fMRI). This allowed researchers to see specific pathways by which the brain solves complex tasks and aids in making decisions as well as reasoning.

“There are two fundamental ways your brain can steer you through life — toward things that are good, or away from things that aren’t working out. Because these processes are happening beneath the hood, you’re not necessarily aware of how much driving one or the other is doing,” said Chantel Prat, associate professor of psychology and co-author of the new study.

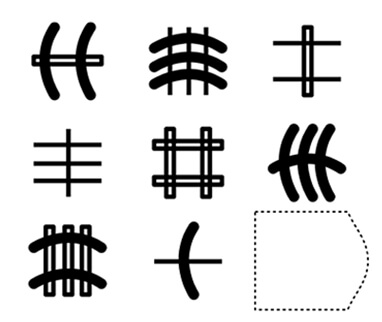

First, a computer model was created to test “advanced” problem-solving skills. The model developed each puzzle as well as the steps required to solve them, then proceeded to decipher the pattern and determine the next step in the sequence in order to solve the puzzle.

Along with pattern deciphering, the model had to determine the location of an image in each sequence, and figure out the rule to complete the overall sequence. During each step, the computer model determined the degree of progress and steered away from any steps that kept it from making progress when given advanced problems to solve. According to the researchers, crucial to problem-solving is the brain’s ability to get back on track when it is off.

To determine the brain’s method of problem-solving, participants were asked to complete a task that required making a decision. Researchers were able to determine the amount of “steering” that took place depending on how often and when a participant moved in the direction of reward and in the opposite direction of opposing things.

The participants were split into three different groups and were asked to solve the first computer puzzle with just a pencil and paper. They then had to decipher another test that analyzed their decision-making skills to choose the best method of solving the puzzle. Results indicate that their success was mostly based on their ability to steer clear of the worst methods when problem-solving, suggesting there was no association between problem-solving success and choosing the best method.

In the second group, participants were asked to solve a computer version similar to the paper and pencil test, however, it was shorter and could be executed in an environment that included MRI scanning of the brain. The results from this test conclude that participants who were best at problem-solving were also great at steering clear of the worst methods.

The third group was asked to solve the puzzles on the computer while simultaneously having the fMRI scan their brains so the researchers could detect with areas of the brain were responsible for successfully solving the puzzles. Researchers found that the “CEO” of the brain, called the basal ganglia, helps the prefrontal cortex make decisions based on 2 paths. One path signals relevant or helpful methods or situations, while the other halts signals that are not helpful or irrelevant.

Results of the tests and the fMRI scans show that the basal ganglia controlled the success of each participant by halting signals of the worst methods to solve the puzzle, thereby, helping them to avoid the wrong problem-solving pathway.

“Our brains have parallel learning systems for avoiding the least good thing and getting the best thing. A lot of research has focused on how we learn to find good things, but this pandemic is an excellent example of why we have both systems. Sometimes, when there are no good options, you have to pick the least bad one! What we found here was that this is even more critical to complex problem-solving than recognizing what’s working,” said Prat.

This study is published in Cognitive Science.