Smiling, even for just a split second, can make neutral or sad-looking faces appear much happier, according to intriguing new research from the University of Essex. The study used a specialized technique to briefly stimulate muscles involved in smiling to explore how facial expressions can alter emotional perceptions.

The research was led by Dr. Sebastian Korb, a psychologist who studies emotion and social cognition. Building on historic work by 19th century neurologist Duchenne de Boulogne and Charles Darwin’s famous photographic studies, Dr. Korb used modern technology to safely and precisely manipulate smiling muscles in study participants. The results suggest that a smile as brief as 500 milliseconds can lead neutral faces to be perceived as happy.

“The finding that a controlled, brief and weak activation of facial muscles can literally create the illusion of happiness in an otherwise neutral or even slightly sad-looking face, is ground-breaking,” Dr. Korb explained in a statement. “It is relevant for theoretical debates about the role of facial feedback in emotion perception and has potential for future clinical applications.”

Zapping Smiles Onto Faces

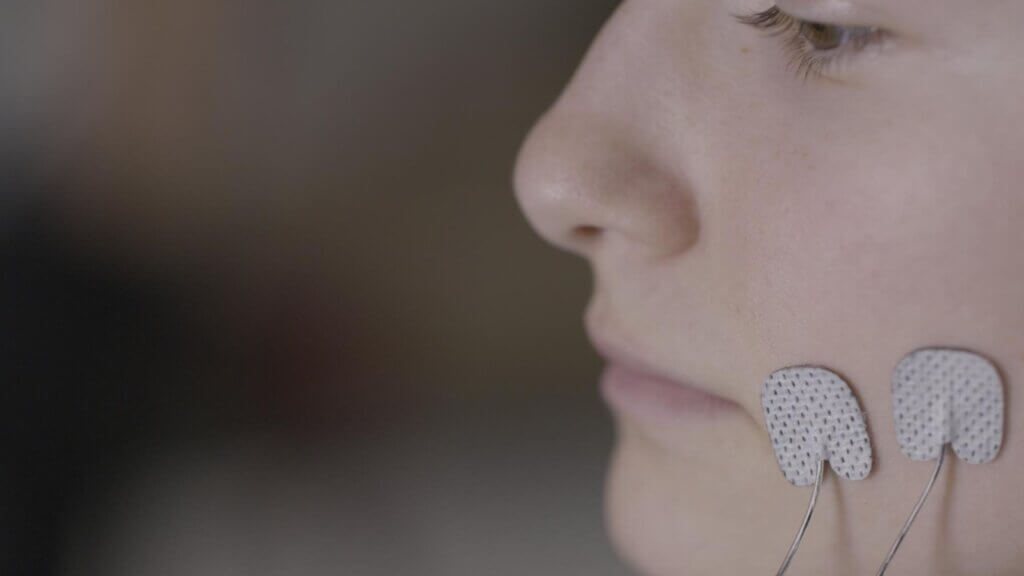

So how exactly did the researchers provoke smiles from participants in the name of science? The study relied on a technique called facial electromyography stimulation, which uses small electrical currents to stimulate nerves connected to facial muscles. The currents cause muscles to contract, forcing the face to form expressions even without any conscious effort from the person.

By precisely controlling the electrical stimulation down to the millisecond, Dr. Korb’s team could spark brief half-second smiles without causing any discomfort to subjects. Most people described the sensation as a slight twitching, itching or tickling, unlike the painful zapping one might feel from static electricity.

Although using electricity to manipulate the body may sound alarming, the current levels involved are quite low and considered safe when procedures are followed appropriately. In fact, forms of electrical muscle stimulation are commonly used in rehab and sports training settings to promote healing or strengthen muscles.

Inspiration from Historic Heavyweights

The clever study design drew inspiration from the innovative work of two scientific legends more than a century ago. In the mid-1800s, Duchenne de Boulogne conducted groundbreaking experiments mapping how electrical stimulation of muscles creates different facial expressions. His technique gave insights into how emotions are displayed through the face.

Seeking to share these discoveries, Duchenne collaborated with a prominent England-based naturalist of the era – none other than Charles Darwin. Darwin documented Duchenne’s experiments using photography, publishing remarkable images of zapped expressions in several books featuring his acclaimed research on evolution and emotion. Dr. Korb’s modern stimulation technique built upon this fascinating historical foundation in social neuroscience.

Putting Smiles to the Test

For their experiment, Dr. Korb’s group showed volunteer participants images of computer-generated avatars displaying neutral expressions. They asked people to look at each face and judge whether it appeared happy or sad.

The key manipulation was that during half of the presentations, the researchers used precisely-timed electrical stimulation to involuntarily provoke a slight smile in the participants’ own faces as they evaluated the avatar. This allowed the researchers to explore how smiling in response to a face, even when completely uncontrolled, might alter perceptions of emotions.

Remarkably, stimulating facial muscles to produce a weak 500 millisecond smile was enough to make participants more likely to rate neutrally-expressing avatars as happy rather than sad. Larger effects occurred after inducing longer smiles.

Delving Deeper into Facial Feedback

The intriguing results provide new evidence that our own facial expressions, even subtle or fleeting ones we don’t notice, can influence how emotions are perceived in others. This mind-body link is known as facial feedback theory in psychology.

Dr. Korb speculates that dynamic facial stimulation techniques could be a tool to shed new light on facial feedback mechanisms and perhaps explore their disruption in psychiatric conditions. Down the line, correcting feedback issues using approaches like neurostimulation could potentially help treat depression or social functioning deficits in autism or Parkinson’s disease.

As a next step, Dr. Korb’s lab is already hard at work on follow-up facial stimulation studies in healthy volunteers. They plan to better characterize the effects and explore impacts on additional social behaviors like trust or empathy.

While applying electrical zaps to faces in the name of science may seem slightly shocking at first glance, this innovative line of research highlights how progress often emerges from unlikely connections. In this case, a 21st century breakthrough built upon a classic 19th century experiment ultimately may offer new ways of easing suffering for psychiatric patients. Just imagine how Duchenne and Darwin might smile about that.

The study is published in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience.