A brain implant to restore the sense of smell is under development by scientists at Virginia Commonwealth University. Their project has been partly funded by a wealthy donor who lost his sense of smell following a skateboarding accident.

Often caused by a brain injury, the condition, known as anosmia, can be a debilitating struggle. It also affects taste, though it doesn’t wipe it out altogether. The VCU researchers are now working on a prototype, based on a cochlear implant which improves hearing.

Anosmia occurs when the nerves in the olfactory bulb, which transfers smell information to the brain, are damaged. For many years, neurophysiologists have been challenged by the difficulty of patients who lose their sense of taste and smell because of the complexity of the olfactory nerve system.

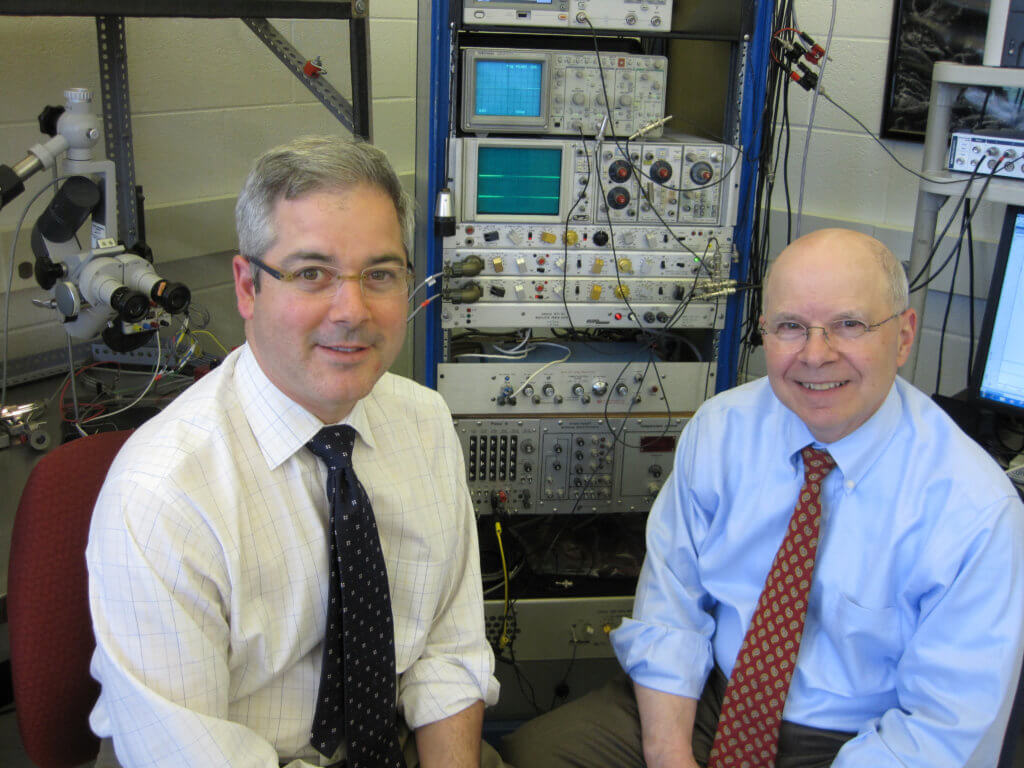

With the hope of offering a solution, neurophysiologist Richard Costanzo and his colleagues have been working in VCU’s Smell and Taste Research Laboratory to develop a prototype device that could restore damaged olfactory functions. Similar to the life-changing technology that cochlear implants bring to those with hearing loss, the researchers have applied the concepts of brain stimulation to restore smell and taste.

Currently, in the development stage, the Olfactory Implant System (OIS) device is providing a new sense of hope to millions of patients with a loss of smell. “Over the last two or three decades I have been finding a way to restore the sense of smell,” professor Costanzo, who teaches in the school’s Department of Otolaryngology, tells South West News Service. “Five to ten years ago, I had this idea that we could bypass the olfactory nerve damage – like in a cochlear implant that stimulates parts of the brain, to restore perceptions of smell – so the people who are suffering would have some sort of way of restoring it.”

The company, Sensory Restoration Technologies was formed after Costanzo and his colleague and cochlear implant surgeon Dr. Daniel Coelho, crossed paths with a man named Scott Moore. Moore is a wealthy individual who had suffered a traumatic brain injury and anosmia in a skateboarding accident.

Both Costanzo and Coelho had come across thousands of patients like Scott before and understood how devastating it had been for him to lose a lifelong sensory experience. Because no other treatments yielded the promising restorative results, they ended up working together, with Scott’s financial backing, to produce a prototype brain stimulation device designed to restore the sense of smell.

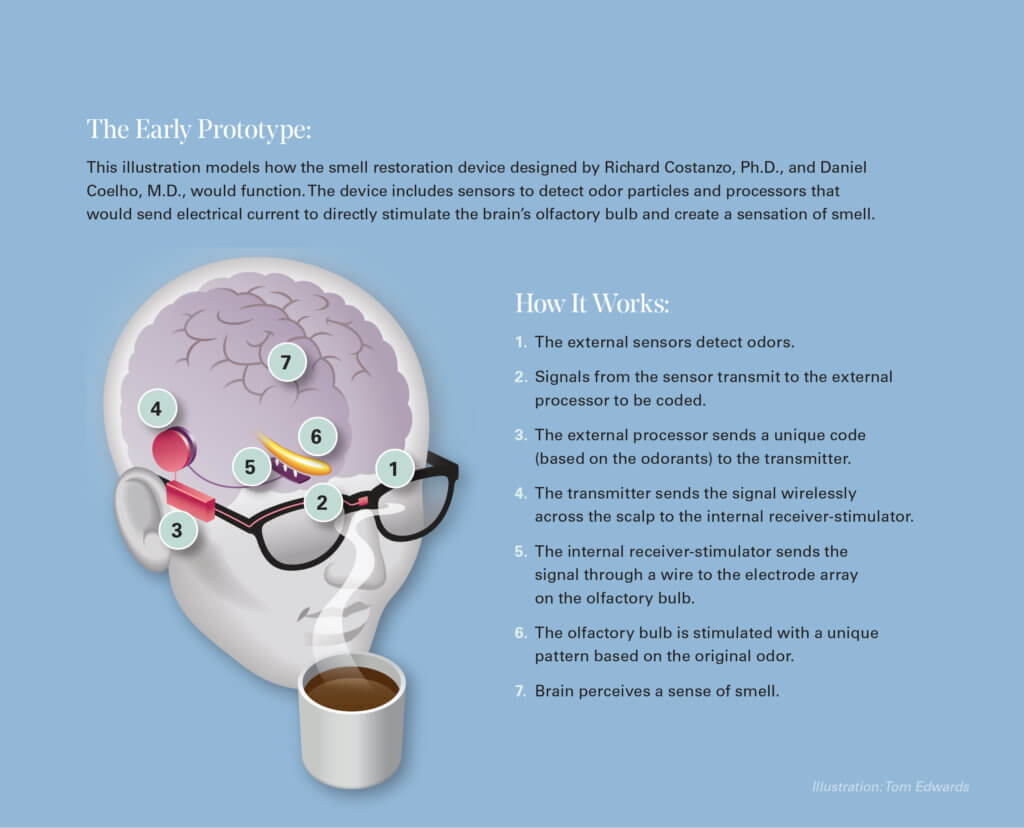

“We patented an idea for how to create an array of sensors that would create a smell fingerprint – so a computer would have a specific code for every smell,” explains Costanzo. “And you would train this device with different odors to have unique fingerprints for those odors.”

The professor went on to explain how similar the device would be to a cochlear implant, used to restore hearing loss in patients.

“No one knows where in the brain the sense of smell is for a banana or an apple and it may not even be in one place,” he says. “But with cochlear implants, once they’re inserted to get the different sounds and frequencies to produce speech, we can individually program those for each patient. So we envisioned the same approach for the olfactory implant to embed the electrons in specific areas of the brain and after asking the patient what things smell like, we can program it to match up to a digital footprint.”

Costanzo’s brain modulation lab at VCU has been described as a “fertile field for research advances.” His team includes some of his former students, including neurosurgeon Dr. Mark Richardson, and ENT surgeon Dr. Eric Holbrook.

To figure out where in the brain the implant would be placed, the researchers jumped on the back of a 24/7 epilepsy monitoring study by stimulating the patients with different odors, while they were being observed. By doing this, they were able to pinpoint what part of the brain was being stimulated by the smells.

“On the back of this study, we will develop electrodes that go into the particular areas of the brain to stimulate them then we can hook them up to our computer to restore the sense of smell,” explains Costanzo.

For those people, like Andrew Lambert from Sussex, England, who suffers from a loss of smell, this device offers more than the prospect of enjoying the taste of food again. The 66-year-old company director at ClearChain in the UK lost his sense of taste and smell after undergoing invasive brain surgery. A tumor in his sinus popped a hole through his skull into the brain.

“I suppose the best way to describe it is that I’ve had dimensions removed from my life and it makes some aspects of my life less enjoyable, while creating unconscious uncertainties,” says Lambert. “For example, before Covid, I went up to a meeting in London. I came out of Oxford Circus station and it was raining. I had a momentary feeling of panic because I couldn’t smell what you would normally smell like ozone, I suppose. Because I couldn’t smell anything, it felt like I had walked into a shower coming out of the station.”

For Lambert, undergoing a procedure to implant Costanzo’s device would not only help him identify everyday dangers like smelling gas, but it would also provide him with the opportunity to participate in social events once more.

“My other senses have been trying to compensate when identifying the texture of food. Memory for me is a very important way of coping, so if I eat something I’ve eaten before, I remember how it tastes and I can get a tiny bit of enjoyment from it,” he tells SWNS. “But with the implant, it would mean that the elements of enjoyment would come back and the uncertainties I have would diminish if not be removed and I wouldn’t have to worry about them anymore. I would also be able to join in with things I can’t currently join in with – like eating out – I can only be an observer, but I could actually be a participant in those events more fully.”

Costanzo explains that people suffering from anosmia, like Lambert and Moore, experience a major drop in quality of life. That’s because not having one’s sense of smell poses a major danger.

“The sense of smell is primitive and as animals, we depend on it to get away from danger. A mouse, for example, can smell danger and they can tell if they are pregnant, so smell is critical for survival and reproduction,” he says. “Humans have evolved and this primitive sense is hardwired in our brains, so when it is lost, it puts our safety at risk. The problem with humans is that the nerves go directly into the brain and when they’re cut, the brain tries to protect itself by causing scarring to protect the damaged tissue, which then prevents any regenerating nerves from getting back to the brain. We can’t yet repair the nerves but if we can map the areas of the brain, we can optimally generate a perception of a smell.”

The professor explains that after years of giving patients the news that there is no cure, he and his team are excited about the future.

“This century, or the next century, we’re going to see the advances in microelectronics, applied to write interfaces, in many different applications. The technologies are advancing technologies and microcomputers have chips that are so small that it’s all coming together in a good way,” he says. “I think there’s some interest in Europe as well as the US, but I’m sure that other countries will probably jump on the bandwagon of our technology as soon as they can. I think the more people that work on this, the better off our solution will be for the patient population.”

Article by South West News Service writer Georgia Lambert

Please let me know how I can find out how the research is progressing, and when the device will be developed. Thank you.

Is there also a solution for people who lost theirv taste? If yes, how do I get the implant?