“I love sleep. My life has the tendency to fall apart when I’m awake, you know?” – Ernest Hemingway

Sleep is as vital for life as oxygen and water. It’s so important that it has launched a medical subspecialty of its own. Ongoing research at the University of Bern in Switzerland identifies how the brain processes emotions during dream sleep. Positive emotions are consolidated and put in storage, while consolidation of negative emotions is diminished. The study reinforces the importance of sleep to mental health and may generate new therapeutic strategies.

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is the sleep state during which most dreams with intense emotional content occur. How these emotions are reactivated is unclear. The prefrontal cortex integrates emotions during wakefulness, but is silent during REM sleep.

“Our goal was to understand the underlying mechanism and the functions of such a surprising phenomenon,” says Prof. Antoine Adamantidis, from the Department of Biomedical Research at the University of Bern, in a statement.

Processing emotions, particularly distinguishing between danger and safety, is critical for animal survival. In humans, powerfully negative emotions can lead to pathological states, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In Europe, about 15 percent of the population is affected by chronic anxiety and severe mental illness. Dr. Adamantidis and his team are studying how the brain reinforces positive emotions and weakens strongly negative or traumatic emotions during REM sleep.

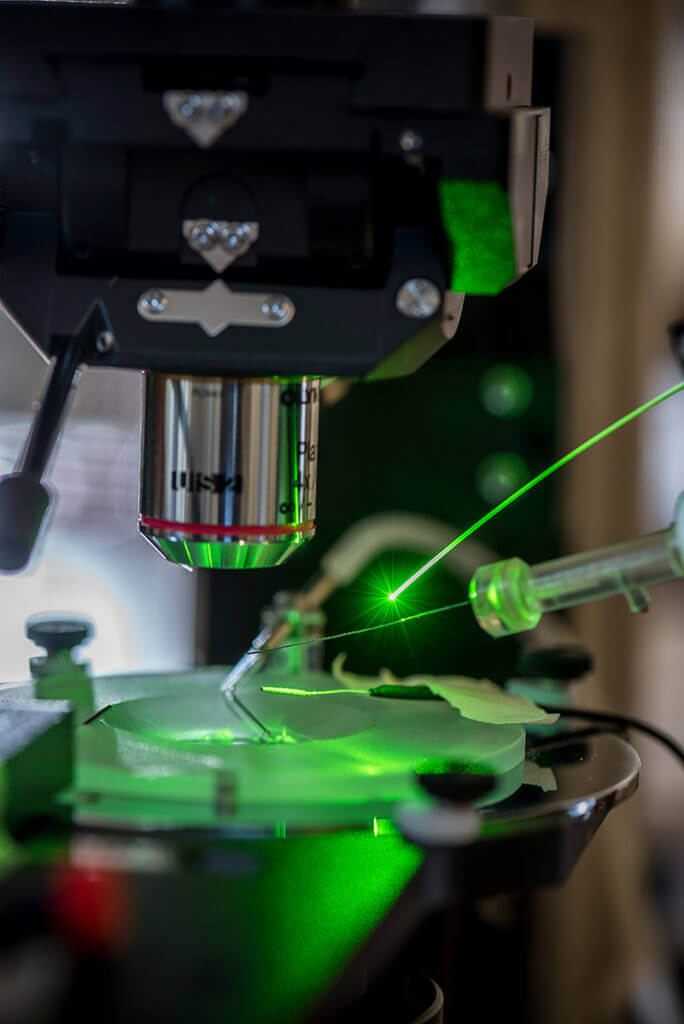

The researchers conditioned mice to recognize some auditory stimuli associated with safety, and some other stimuli associated with danger (aversive stimuli). They recorded neuron activity in the brains of the conditioned mice during sleep-wake cycles. It enabled the researchers to map how different areas of a cell are transformed during REM sleep. They found that the brain favors the safety signals over aversive signals, blocking over-reaction to negative emotions, especially danger. The differential processing of emotions with opposing natures and degrees of significance has been described as “decoupling.”

If this discrimination is missing in humans, and excessive fear reactions are generated, it can lead to anxiety disorders. The findings are particularly relevant to pathological conditions such as PTSD, in which trauma is over-consolidated in the prefrontal cortex, day after day, during sleep.

These findings, published in the journal Science, pave the way to better understanding of the processing of emotions during sleep in humans. They may reveal potential therapeutic targets to treat maladaptive processing of traumatic memories and their early, sleep-dependent consolidation. Additional acute or chronic mental health issues that may implicate this decoupling during sleep include acute and chronic stress, anxiety, depression, panic, and anhedonia, which is the inability to feel pleasure.

“We hope that our findings will not only be of interest to the patients, but also to the broader public,” says Adamantidis.

Dear readers: “Good night – may you fall asleep in the arms of a dream, so beautiful, you’ll cry when you awake.” – Michael Faudet