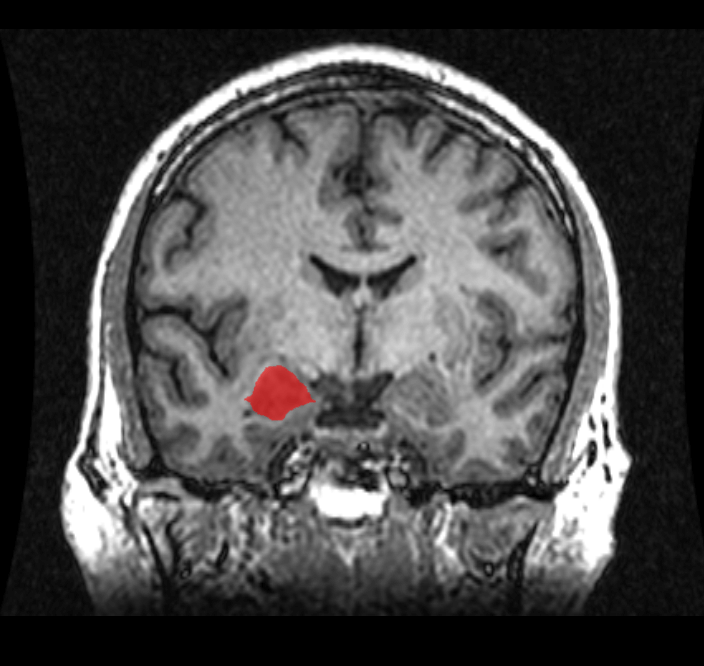

Tufts University researchers led the first study which shows that alcohol is capable of altering activity in the basolateral amygdala in mice — the area of the brain responsible for processing emotions. Researching the various signals generated in this area helps to better understand how they contribute to feelings like anxiety and fear.

“We know one of the reasons people drink is to relieve anxiety or stress, which are associated with this area of the brain,” says first author Alyssa DiLeo, a doctoral student at the time of the study, in a statement.

As such, using alcohol as means of determining changes in the brain’s network may help detect changes in mood and the progression toward alcohol abuse. The researchers found that alcohol can shift the brain from a tense state to a relaxed one. Specifically within the basolateral amygdala, a receptor called the delta subunit-containing GABA-A receptor is an important part of the signaling receptor that causes the switch.

Researchers also noticed a slight difference between males and females. Females required more alcohol to see a shift in mental state, which was possibly explained by females have less of the receptors involved. In male mice, they deleted some of the receptors not found in the females, and they responded the same.

“That tells us that these receptors are playing a role in these sex differences and how alcohol affects the basolateral amygdala network,” says Jamie Maguire, a professor in the neuroscience department at Tufts University School of Medicine and a member of the neuroscience program faculty at the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences (GSBS).

By understanding the internal interactions that activate switching between positive and negative network states in the basolateral amygdala, the researchers may find potential therapeutic targets to help people treat mood disorders and alcohol or drug addiction. It won’t be a simple process, the researchers point out. Mental health isn’t just flipped on and off like a switch, but this can help strike a balance to help people manage their negative thoughts better.

“You don’t want to just take out the fear; you don’t want to take out the sadness; you don’t want to take out the stress, because there are good reasons that we feel stressed and fearful of things,” says Eric Teboul, a GSBS doctoral student in Maguire’s lab and lead author on the paper.

The study is published in the journal eNeuro.