Receiving a cancer diagnosis can be life-shaking news. Upon diagnosis, many things change in an instant. Suddenly, the patient is left with a hurricane of considerations and treatment options. Each year, about 650,000 cancer patients receive chemotherapy in an outpatient oncology clinic in the United States. The survival rate for those diagnosed in stages 1-3 is near 100% and about 71% for stage 4.

The treatment, however, comes with serious complications. Pain and fatigue, along with sensory, motor, and cognitive disorders, are chief among the grueling symptoms that chemo patients suffer while trying to combat their cancer.

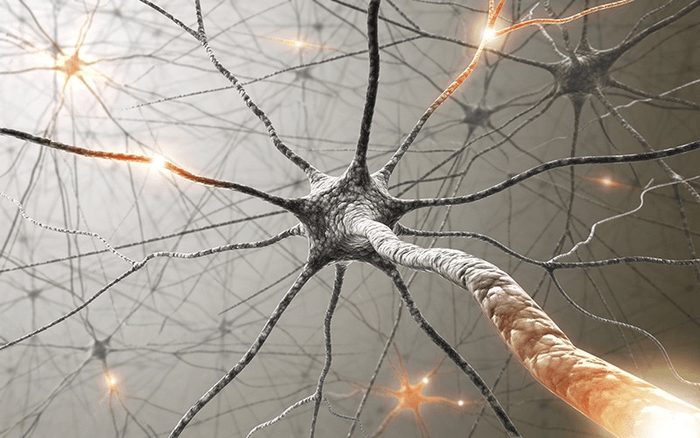

A new study by Georgia Tech researchers in the lab of Timothy C. Cope has found a novel pathway for understanding why these debilitating conditions happen for cancer patients. The study draws attention to why scientists should focus on all of the possible neural processes that deliver sensory or motor problems to a patient’s brain, including the central nervous system. The new findings could impact the development of effective treatments to restore cancer patients’ abilities to receive and process sensory input.

“Chemotherapy undoubtedly negatively influences the peripheral nervous system, which is often viewed as the main culprit of neurologic disorders during cancer treatment,” says study lead author Stephen N. (Nick) Housley, a postdoctoral researcher at Georgia Tech, in a statement. However, he says, for the nervous system to operate normally, both the peripheral and central nervous system must cooperate.

Originally, researchers have linked only the degeneration of the peripheral nervous system with the decline of motor-sensory abilities that occur in patients post-chemo treatments. “Through an elegant series of studies, we show that those hubs of communication in the central nervous system are also vulnerable to cancer treatment’s adverse effects,” Housley shares. He explains that the findings force “recognition of the numerous places throughout the nervous system that we have to treat if we ever want to fix the neurological consequences of cancer treatment, because correcting any one may not be enough to improve human function and quality of life.”

“These findings have broad impact on the scientific field and on clinical management of neurologic consequences of cancer treatment,” Housley continues. “As both a clinician and scientist, I can envision the urgent need to jointly develop quantitative clinical tests that have the capacity to identify which parts of a patient nervous system are impacted by their cancer treatment.”

Researchers believe that having the capacity to monitor neural function across various sites during the course of treatment will provide a biomarker to give doctors a map for ideal treatment. Housley says that as we move into the next generation cancer treatments, “clinical tests that can objectively monitor specific aspects of the nervous system will be exceptionally important to test for the presence off-target effect.”

This potential treatment will not reverse the devastation of a cancer diagnosis, nor will it remove the hardship of chemotherapy treatment. It does however give hope that, after survival, chemo patients will be able to regain what sensory-motor abilities they have lost and continue enjoying the life they worked so hard to save.

This article is published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Article written by Rhonda Errabelli

Very interesting, Steve. This explains a lot – I finished chemotherapy in August 2020 and radiotherapy in October 2020 and although I am healthy and well, I feel that I have been left with damage to my central nervous system – I do have some peripheral neuropathy but there are other changes that I can’t really explain to anyone. Sometimes, I feel like I am not in complete control of my legs although I appear to be walking ok, sometimes I get a weird feeling in my head a bit like vertigo but not and I am nervous about going for walks by myself or driving long distances by myself and yet I play golf and bridge and help with grandkids but I don’t feel the same as I did before chemo.