Who says robots can’t have feelings? New research from the University of Cambridge found that their creation of a humanoid robot did better at detecting children’s emotions and overall mental well-being than parents. The research team suggests the robot could be a regular visitor in psychology offices where children are assessed for their mental health.

One reason behind the robot’s enhanced detection of a child’s mental health is that children feel confident disclosing secrets to the friendly-looking toy. They appear more likely to share information they may not have reported in online or in-person questionnaires measuring mental health.

Children’s mental health took a serious toll during the COVID-19 pandemic. As the virus spread, many children were forced to isolate themselves from friends and undergo online or homeschooling for long periods of time.

“After I became a mother, I was much more interested in how children express themselves as they grow, and how that might overlap with my work in robotics,” says Hatice Gunes, a researcher at the University of Cambridge and coauthor of the study, in a statement. “Children are quite tactile, and they’re drawn to technology. If they’re using a screen-based tool, they’re withdrawn from the physical world. But robots are perfect because they’re in the physical world – they’re more interactive, so the children are more engaged.”

Collaborating with a team of psychiatrists, roboticists, and computer scientists, Gunes designed a robot used to measure the mental well-being of children. “There are times when traditional methods aren’t able to catch mental well-being lapses in children, as sometimes the changes are incredibly subtle,” explains Nida Itrat Abbasi, the study’s lead author. “We wanted to see whether robots might be able to help with this process.”

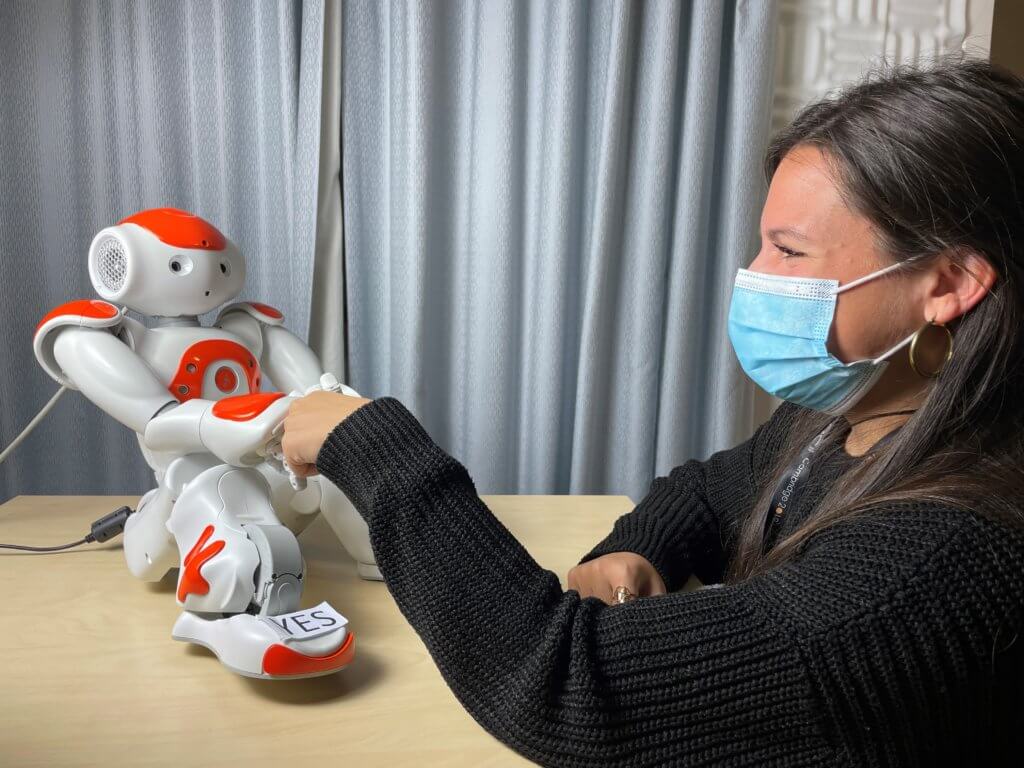

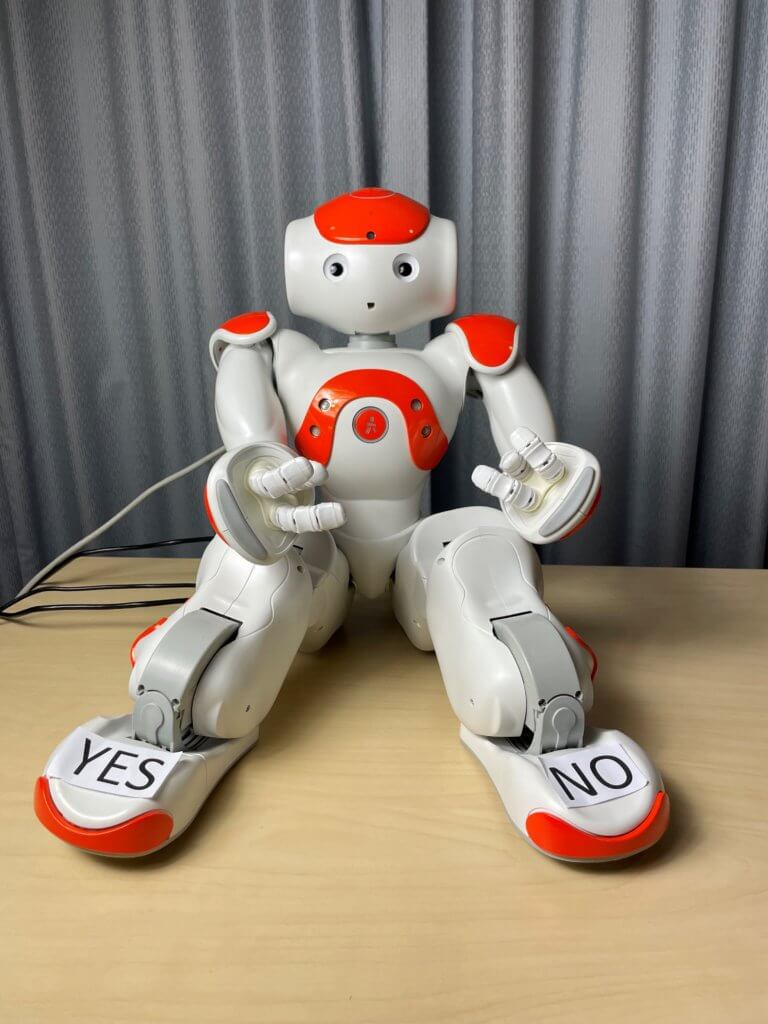

Twenty-eight children between the ages of 8 and 13 interacted one-on-one with a Nao robot for 45 minutes. The Nao robot stands at almost 27 inches and looks like a humanoid robot. While children talked with the robot, their parent or guardian along with members of the research team, looked on in another room. Before the session started, children and their parents or guardian filled out an online questionnaire on the child’s mental well-being.

The robot “conversed” with the child in four different ways. First, it asked the kids open-ended questions about happy and sad memories of the last week. Next, it asked children questions from the standard mood and feelings questionnaire. Depending on the results, children were divided into three groups that showed how likely they were to struggle with their mental health.

The robot then showed children a picture inspired by the Children’s Apperception Test and give them a task for it. Finally, it administered the Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale to measure for symptoms related to generalized anxiety, panic disorder, and low mood. Children interacted with the robot by talking to it or touching sensors on the robot’s hands and feet. Other sensors placed in the robot tracked the participant’s heartbeat, head, and eye movement throughout the session.

All the children said they enjoyed talking to the robot. Some even felt confident enough to confide in the robot, telling it things that were not disclosed in person or on the online questionnaire.

Children having issues with mental well-being interacted differently than those that did not. While all had positive experiences with the robots, those with well-being related concerns felt more assured in divulging their true feelings and experiences.

“Since the robot we use is child-sized, and completely non-threatening, children might see the robot as a confidante—they feel like they won’t get into trouble if they share secrets with it,” adds Abbasi. “Other researchers have found that children are more likely to divulge private information—like that they’re being bullied, for example—to a robot than they would be to an adult.”

Study authors clarify the robot is not meant to replace mental health professionals but could be a helpful tool for assessing children who may not feel comfortable opening up at first. The team is working to expand the usefulness of the robot’s design. They plan to enroll more children in the study and test to see if talking with the robot via video chat will achieve a similar outcome.

The research was presented on September 1, 2022, at the 31st IEEE International Conference on Robot & Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) in Naples, Italy.