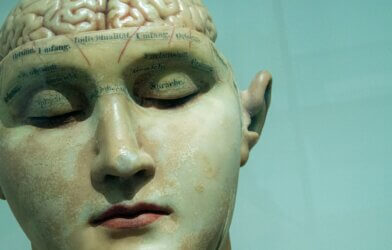

“Brain Plasticity Myth Busted: Our Brains Don’t ‘Rewire,’ Say Cambridge Scientists”

In a groundbreaking study challenging a widely accepted belief, scientists from the University of Cambridge and Johns Hopkins University argue that the brain does not possess the ability to rewire itself in response to injury or deficits, contrary to conventional wisdom.

Published in eLife, Professors Tamar Makin (Cambridge) and John Krakauer (Johns Hopkins) dispute the idea that the brain can reorganize itself and repurpose specific regions for new functions, often cited in scientific textbooks. Instead, they propose that the brain is trained to utilize existing latent abilities.

A common example is blind individuals developing heightened hearing abilities, supposedly due to the visual cortex rewiring to process sounds. However, Makin and Krakauer argue that the brain is merely enhancing or modifying its pre-existing architecture, not creating entirely new functions.

Krakauer explained, “The idea that our brain has an amazing ability to rewire and reorganize itself is an appealing one. It gives us hope and fascination, especially when we hear extraordinary stories of blind individuals developing almost superhuman echolocation abilities, for example, or stroke survivors miraculously regaining motor abilities they thought they’d lost.”

The researchers examined ten seminal studies claiming to show the brain’s ability to reorganize and argued that, while the studies demonstrate the brain’s capacity to adapt to change, it is not creating new functions in unrelated areas but utilizing latent capacities present since birth.

Makin’s research in 2022, involving a nerve blocker to mimic the effect of amputation, challenged a study from the 1980s. The previous study suggested that the brain rewired itself after finger amputation, but Makin’s findings indicated that existing signals from other fingers were already present and were intensified following amputation.

Makin stated, “The brain’s ability to adapt to injury isn’t about commandeering new brain regions for entirely different purposes. These regions don’t start processing entirely new types of information.”

Another counterexample highlighted was a study of congenitally deaf cats, whose auditory cortex appeared repurposed for vision. However, when fitted with cochlear implants, the auditory cortex resumed processing sound, suggesting that the brain did not rewire.

Examining various studies, the researchers found no compelling evidence that the visual cortex of individuals born blind or the uninjured cortex of stroke survivors developed novel functional abilities that did not otherwise exist.

Makin and Krakauer do not dismiss stories of blind individuals navigating through hearing or stroke survivors regaining motor functions but argue that the brain enhances or modifies pre-existing architecture through repetition and learning.

Makin emphasized, “So many times, the brain’s ability to rewire has been described as ‘miraculous’ – but we’re scientists, we don’t believe in magic. These amazing behaviors that we see are rooted in hard work, repetition, and training, not the magical reassignment of the brain’s resources.”

The study challenges the perception of brain plasticity and highlights the importance of understanding its true nature and limits for realistic expectations in patient treatment and rehabilitation approaches.