It can be incredibly frustrating for older people with age-related cognitive decline to barely remember what the person they spoke to earlier the same day looks like. And when it happens to people during middle age, many just laugh it off to part of the aging process. But why this happens still isn’t so clear to neurologists and brain experts. While the mechanisms explaining this are still unknown, a new study University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) study provides some helpful starting points, identifying a possible neuron target for new therapies.

Previously, study leader Michel Kelly, PhD, developed research on the enzyme PDE11A, which is required for the brain to gather all the necessary pieces to create memories, especially in social interaction. She and her team found that mice with genetically similar versions of the PDE11 enzyme were more likely to interact than mice with a different form of it. In this most recent work, Dr. Kelly is taking it a step further and wants to determine PDE11A’s role in social associative memory in aging minds, exploring the possibility of altering the enzyme to prevent associated memory loss.

Researchers are capable of studying interactions between mice by determining if they are interested in trying new foods, and testing their memories of recognizing that food on the breath of another mouse. Generally, mice are skeptical of trying new foods because they could get fatally ill. By smelling the food on another mouse, they can register the odor as safe for them to eat the associated food when they see it. Dr. Kelly and her team discovered that old mice could distinguish between food and social odors, but they were not able to remember the association between the two, or create a mental note of safety.

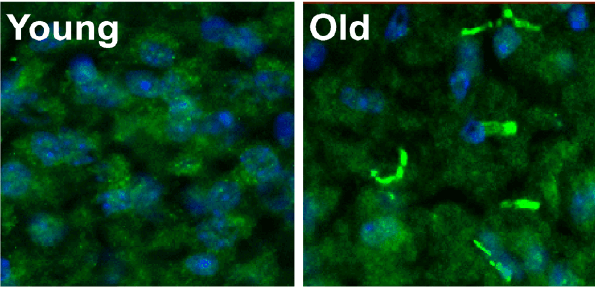

Further, they discovered that levels of PDE11A increased with age in both humans and mice in the hippocampal region, which is like a hub for learning and memory in the brain. While you can find this enzyme in the same area in young mice, a key difference is that it also accumulated as small filaments in neuronal compartments.

This prompted the team to wonder if this behavior was responsible for older mice not recalling whether a food they smelled on another mouse was safe or not, and no longer eating the food. To test this, they genetically deleted the PDE11A gene in mice to prevent its buildup. The older mice proceeded to eat the safe food they ate. When the researchers added the enzyme back in, their memory suffered again and they no longer consumed the food.

The researchers are confident in using their findings as a basis for age-related cognition drug development. However, they also warn that PDE11 is useful for normal memory and learning processes, so just targeting the excess filaments outside of the hippocampus should be the main focus in their future works.

“PDE11 is involved in more things that just memory, including preferences for who you prefer to be around. So, if we are to develop a therapy to help with cognitive decline, we would not want to get rid of it entirely or it could cause other negative side effects,” says Dr. Kelly in a statement.

She and her colleagues joke that any drug that eliminated PDE11 would ensure you would remember your friends and family, but you may no longer like them. “Thus, our goal is to figure out a way to target the bad form of PDE11A specifically, in order to not interfere with the normal, healthy function of the enzyme.”

This study is published in the journal Aging Cell.