Inside your head, a seahorse-shaped brain area is responsible for all of your memories. The role of the hippocampus in forming and storing memories is clear, but what’s not clear is how it’s done. A new mouse study from Denmark sheds light on a brain cell and its important job in creating episodic memories.

Episodic memories are memories of everyday events and the conscious recollection of the past. The hippocampus uses brief and high-frequency electrical events known as sharp-wave ripples (SWRs), which may be the reason you’re able to recall your friend’s birthday or the name of your favorite restaurant when you were five years old. Though what happens when these electrical signals are generated remained unknown until now.

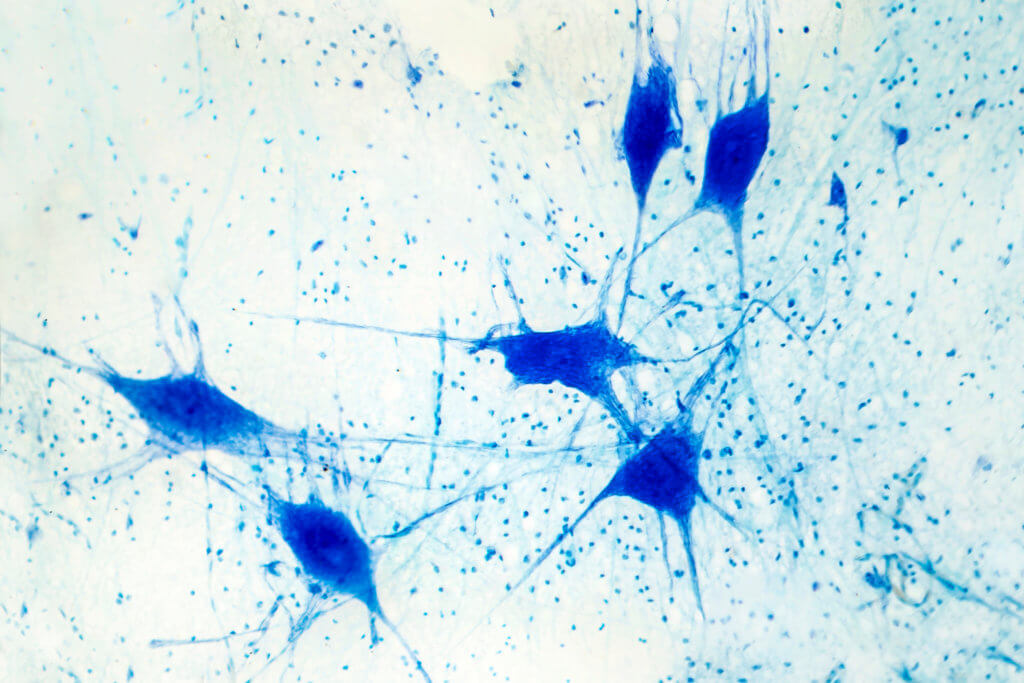

The researchers report a never before seen type of brain cell in the hippocampus called theta off-ripples on (TORO). “We have found that this new type of neuron is maximally active during SWRs when the animal is awake – but quiet – or deeply asleep. In contrast, the neuron is not active at all when there is a slow, synchronized neuronal population activity called “theta” that can occur when an animal is awake and moves or in a particular type of sleep when we usually dream,” explains Marco Capogna, a professor at Aarhus University in a media release.

The discovery of this new nerve cell could help experts understand the complex connectivity the hippocampus has with nerve cells and other brain areas. Capogna and his team used a tool called electrophysiology to detect brain cell activity and imaging to observe signaling changes within the cell.

Additionally, the research team used circuit mapping to study how TOROs link up with other brain cells in the hippocampus to answer why TORO-neurons are sensitive to SWRs. They found that TORO-neurons are activated by CA3-pyramidal neurons and inhibited by messages from brain areas such as the septum.

“Furthermore, the study finds that TOROs are inhibitory neurons that release the neurotransmitter GABA. They send their output locally – as most GABAergic neurons do – within the hippocampus, but also project and inhibit other brain areas outside the hippocampus, such as the septum and the cortex. In this way, TORO-neurons propagate the SWR information broadly in the brain and signal that a memory event occurred,” Capogna explains.

The next step in the research is to show evidence of a causal link between TORO-nerve cell activity in all types of memory. This may include people with impaired memories as seen in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

The study is published in Neuron.