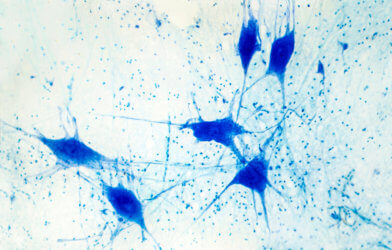

Multiple sclerosis (MS) patients typically face diagnosis of the debilitating condition well after beginning to notice symptoms. Their immune system starts attacking their brain and spinal cord, leading to symptoms like dizziness, muscle spasms, fatigue, and even loss of the ability to walk. It’s a scary diagnosis, but what if it could be caught much earlier, before the worst symptoms appear? A team of scientists from University of California-San Francisco (UCSF) may have found a way.

In a landmark study published in Nature Medicine, UCSF researchers discovered that in about 10 percent of MS cases, the body starts producing distinctive antibodies against its own proteins years before any symptoms show up. These autoantibodies seem to mistake normal human proteins for viral invaders, possibly triggering the immune attacks that cause MS.

What exactly did researchers find? Using a clever technique called phage display, scientists screened blood samples from 250 MS patients, both from after their diagnosis and from five-plus years earlier when they first joined the military. For comparison, they also looked at blood from 250 healthy veterans.

What they expected was a spike in autoantibodies right as the first MS symptoms appeared. But surprisingly, 10 percent of the MS patients had high levels of about a dozen specific autoantibodies many years before being diagnosed. And here’s the kicker — having that autoantibody “signature” was 100 percent predictive of later being diagnosed with MS, across two separate patient groups.

“When we analyze healthy people using our technology, everybody looks unique, with their own fingerprint of immunological experience, like a snowflake,” says senior study author Dr. Joe DeRisi, president of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub San Francisco, in a media release. “It’s when the immunological signature of a person looks like someone else, and they stop looking like snowflakes that we begin to suspect something is wrong, and that’s what we found in these MS patients.”

The autoantibodies all bound to proteins that resembled ones found in common viruses like Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Over 85 percent of people get infected with EBV at some point, and previous studies have suggested it may contribute to MS. Researchers speculate that in some cases, the immune system may be confusing human proteins for EBV or other viruses, leading to a mistaken attack.

The discovery is a big deal because currently, diagnosing MS isn’t always straightforward. Symptoms can resemble other conditions, and doctors have to carefully analyze MRI brain scans. But a simple blood test for these autoantibodies could let patients know much sooner that MS is brewing, so they can start treatments earlier.

“Over the last few decades, there’s been a move in the field to treat MS earlier and more aggressively with newer, more potent therapies,” notes senior study author Dr. Michael Wilson, neurologist at UCSF. “A diagnostic result like this makes such early intervention more likely, giving patients hope for a better life.”

There’s still a lot we don’t understand about MS, like what triggers the autoimmune response in some patients and how the disease develops in the other 90 percent who don’t show this autoantibody pattern. But the ability to definitively detect MS years before diagnosis could be game-changing.

“Imagine if we could diagnose MS before some patients reach the clinic,” concludes senior study author Dr. Stephen Hauser, director of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences. “It enhances our chances of moving from suppression to cure.”

A blood test to see MS coming far in advance would let patients get a crucial head start on treatment to slow the disease and preserve abilities like walking. With around a million Americans living with MS, this research shines a much-needed ray of light.

-392x250.jpg)