Memorizing a math equation or learning to play an instrument is a part of life for most students. Of course, some of those equations can be just as hard to remember as the notes of a song. Scientists have been looking into what happens with learning for memory on a neuronal level for some time, specifically in conditions where cognitive function is impaired.

The FMRP protein, which performs a variety of functions in memory neurons, plays a crucial role in learning. Without it, conditions like fragile X syndrome, some types of autism, and intellectual disorders are seen. Although this is already widely accepted, a new study reveals that this protein may play an even greater role than previously thought.

Through examining the hippocampal area (the brain structure designed for memory) of mouse brains, Rockefeller University scientists discovered that the FMRP protein regulates proteins necessary for strengthening connections between other neurons. It also controls overall genetic expression within the cell body of them. Further, more than 900 ribonucleic acids (RNA) are known to be bounded and managed by this protein.

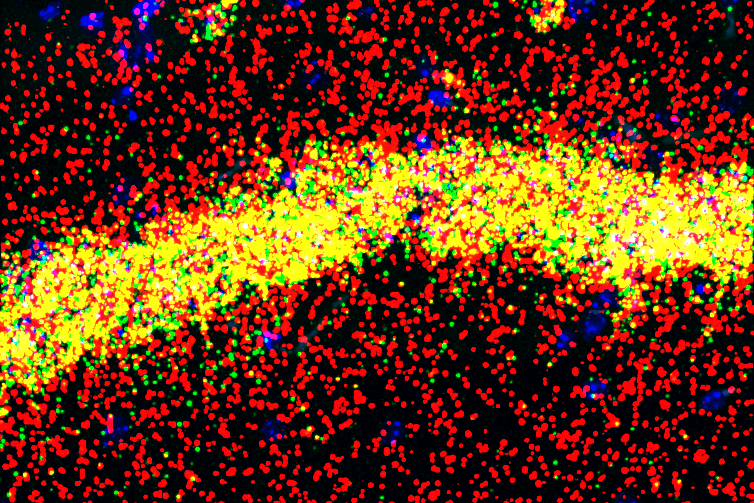

To gain an in-depth understanding, the Rockefeller researchers marked each individual neuron using molecular genetic techniques before dissecting and separating neural synapses and cells manually. They then used an antibody-based technique to analyze the isolated RNA complexes.

“By micro-dissecting the brain tissue, we were able show that this protein controls distinct functions at different cellular locations,” says Robert B. Darnell, Rockefeller’s Robert and Harriet Heilbrunn Professor and HHMI Investigator, in a statement.

These findings may provide a gateway to understanding autism and other learning impairment conditions, as they conclude that the FMRP protein assists in creating a feedback loop between the cell body and dendrites, keeping neurons under tight regulation. If they are let loose, “they could keep getting more and more excited, ultimately leading to a seizure, a phenomenon seen in fragile X syndrome,” Darnell explains.

This study is published in eLife journal.