One of the most difficult concepts to instill in first-time parents of a new baby is that their child is not going to starve to death if they don’t start feeding the wee bairn solid food in the first month of life. Children eating well (or not) seems no less than the yardstick by which we measure our success as a parent. Now, there’s good news for kids with neuromuscular eating disorders. Scientists at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute in Virginia discovered new features about the brain, cranial nerves, and how they work together in eating, swallowing and speech.

The early development of pain-sensing and movement-sensing neurons in the face and throat are key to their discovery.

“We were able to show for the first time that this momentary interaction between two groups of cells plays a crucial role in regulating movement and pain-sensing innervation in the face,” says Anthony-Samuel LaMantia PhD, professor and director of the Institute’s Center for Neurobiology Research, in a statement.

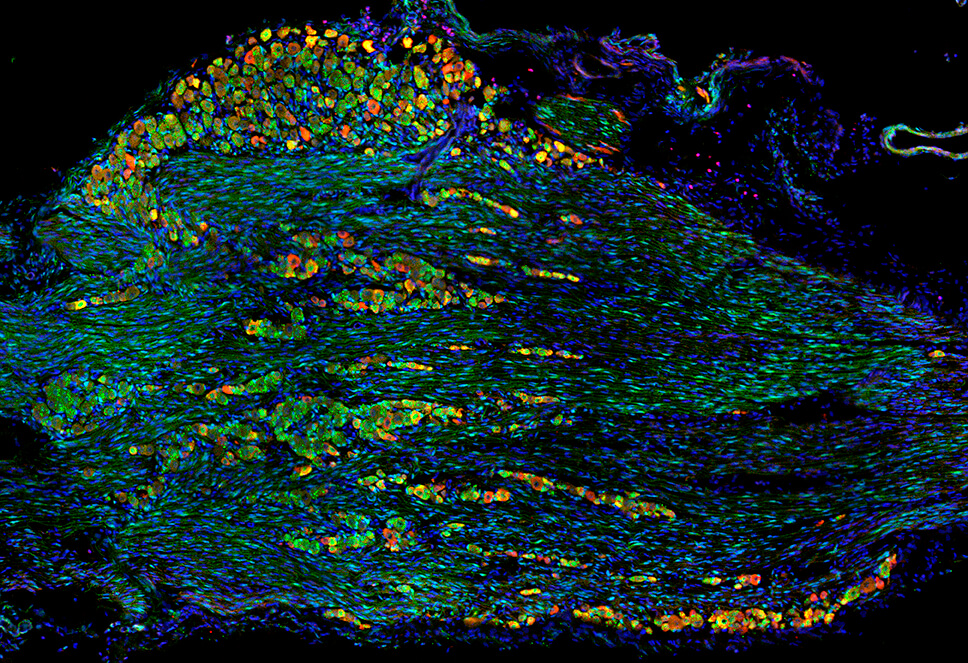

The researchers examined early neural development in mice embryos with DiGeorge syndrome, a rare genetic disorder associated with neural and facial abnormalities. Like human patients born with DiGeorge, mice can carry the identical genetic mutation for DiGeorge syndrome, making an ideal research model.

Children with DiGeorge syndrome commonly have trouble coordinating suckling and swallowing. It’s unclear how the mutation causes dysphagia. Motor neurons control mouth, tongue, and throat movements. Mechanosensory neurons detect and integrate movement signals to coordinate the behaviors. The study also evaluated pain-sensing receptors, which monitor for potential harm, such as excessive temperatures and irritants like capsaicin in peppers.

Based on prior research, LaMantia’s team knew that on day nine of embryonic development, neural crest and placode cells meet to begin forming the facial nerve. They knew that in the syndromic mice, if something went wrong at this stage of development, it could have adverse consequences.

“Starting out, we weren’t sure if these two groups of cells just weren’t migrating together to meet in the proper place, or if they were in the right place at the right time, and failed to communicate,” LaMantia said.

The new data suggest that the latter is true.

Researchers found that neural crest cells were turning into pain-sensing neurons prematurely, causing the quantity of placode cells to increase relative to neural crest cells.

The new discovery reveals how changes in gene expression associated with DiGeorge syndrome destabilize sensory neuron growth by interrupting a key interaction between neural crest and placode cells. LaMantia’s team now hopes to identify the molecular signals needed to form a healthy cranial nerve.

“Now that we’ve identified the point of divergence where these functional oropharyngeal problems originate, our next step will be to understand the vocabulary these cells use to communicate with each other,” LaMantia says.

The study is published in Disease Models & Mechanisms.