Communication doesn’t always require words, which are easily forgotten, but those you serve will always remember the way you made them feel. This is a lesson for my family medicine trainees that I’ve long repeated. Now, a team of biomedical engineers at the prestigious Columbia University have conducted a study which identified a neural mechanism within the human brain specifically for tagging information with emotional associations for memory enhancement.

Memory disorders are becoming more prevalent

The rising incidence of dementia and other memory disorders has made it clear that memory loss can have devastating effects on individuals and communities. Depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are all associated with memory disturbances. Understanding how information is prioritized for storage could provide evidence of pathways to new treatments for enhancing the formation of memories in individuals at risk of memory loss or dysregulation.

According to Salman E. Qasim, PhD, lead author of the study, in a statement: “It’s easier to remember emotional events, like the birth of your child, than other events from around the same time. The brain clearly has a natural mechanism for strengthening certain memories, and we wanted to identify it.”

Studying brain-wave patterns of emotional words

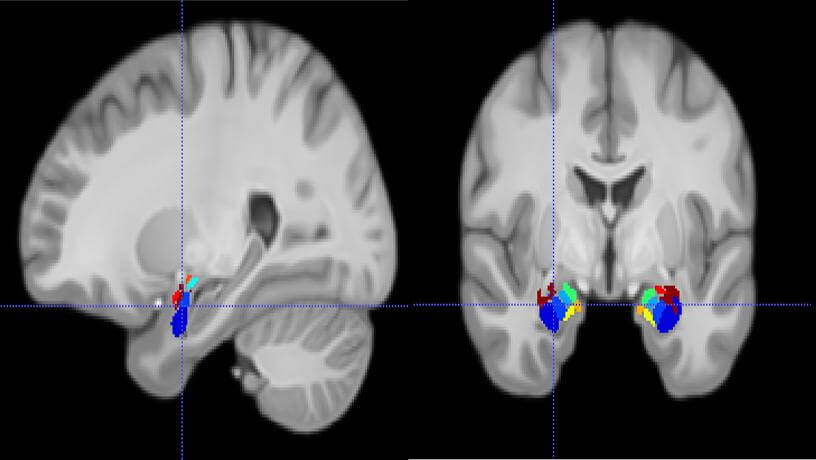

The team demonstrated that high-frequency brain waves in the amygdala, a hub for emotional processes, and the hippocampus, a hub for memory processes, are critical to enhancing memory associated with emotional stimuli. Disruptions to this neural mechanism, brought on either by electrical brain stimulation or depression, impair memory, specifically for emotional stimuli.

The researchers analyzed this pattern across a large data set of 147 patients and found a clear link between participants’ enhanced memory for emotional words and the prevalence in their brains of high-frequency brain waves across the amygdala-hippocampal circuit.

“Finding this pattern of brain activity linking emotions and memory was very exciting to us, because prior research has shown how important high-frequency activity in the hippocampus is to non-emotional memory,” said Jacobs. “It immediately cued us to think about the more general, causal implications—if we elicit high-frequency activity in this circuit, using therapeutic interventions, will we be able to strengthen memories at will?”

To establish whether this high-frequency activity reflects a causal mechanism, Jacobs and his team developed a unique method to replicate the kind of experimental disruptions typically reserved for animal research. They found that electrical stimulation clearly and consistently impaired memory for emotional words. This stimulation also diminished high-frequency activity in the hippocampus. This provided causal evidence that interrupting the pattern of brain activity that correlated with emotional memory selectively diminishing emotional memory.

Depression can mimic brain stimulation

Qasim also analyzed patients’ emotional memory with mood assessments characterizing the patients’ psychiatric states. In the patients with depression, they observed a simultaneous decrease in emotion-mediated memory and high-frequency activity in the hippocampus and amygdala.

“Our emotional memories are one of the most critical aspects of the human experience, informing everything from our decisions to our entire personality,” Qasim added. “Any steps we can take to mitigate their loss in memory disorders or prevent their hijacking in psychiatric disorders is hugely exciting.”

This study is published in the journal Nature Human Behaviour.