As we enter our middle years, many of us find it increasingly difficult to maintain a healthy weight. Despite our best efforts to eat well and stay active, the numbers on the scale seem to creep up, and our waistlines expand. While this phenomenon is often attributed to a slowing metabolism, researchers from Nagoya University and their colleagues in Japan have uncovered a more complex explanation, one that lies within the intricate workings of our brains.

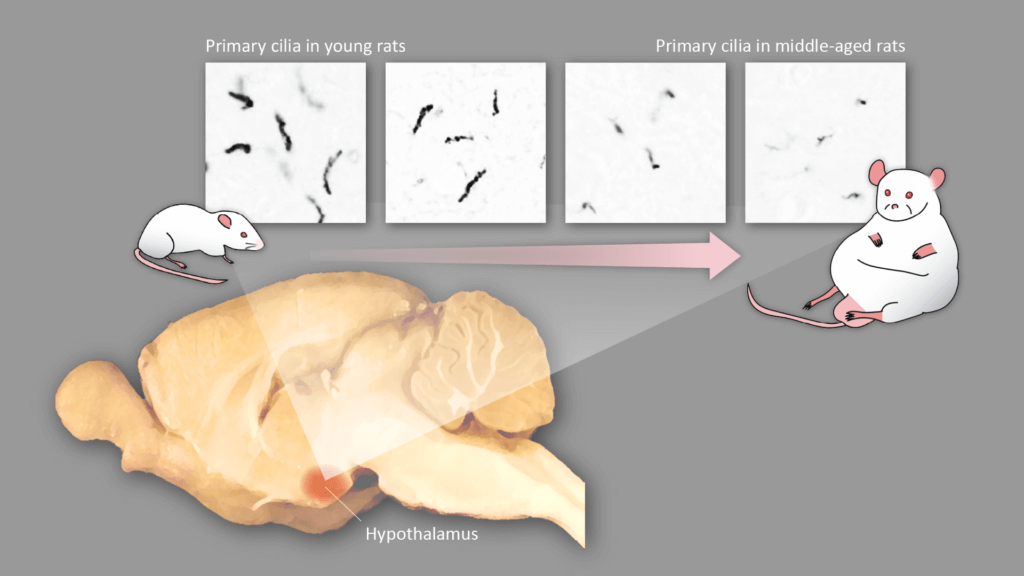

The study, published in the journal Cell Metabolism, focuses on a region of the brain called the hypothalamus, which plays a crucial role in regulating metabolism and appetite. Within the hypothalamus, a protein called melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) acts as a watchdog, detecting overnutrition and signaling the body to burn excess fat. However, the researchers found that as rats aged, the shape of the neurons containing MC4Rs changed, leading to a decrease in the receptors and, consequently, weight gain.

The Incredible Shrinking Cilia

The key to this discovery lies in the primary cilia, tiny antenna-like structures that extend from the neurons in the hypothalamus. These cilia house the MC4Rs, and the researchers found that as the rats grew older, the cilia became shorter. This shrinkage was particularly pronounced in middle-aged rats, whose cilia were significantly shorter than those of their younger counterparts.

“We believe that a similar mechanism exists in humans as well,” said lead author Professor Kazuhiro Nakamura of the Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, in a statement. “We hope our finding will lead to a fundamental treatment for obesity.”

The implications of this finding are significant, as obesity is a major risk factor for a host of chronic diseases, including diabetes, heart disease, and certain types of cancer. According to the World Health Organization, worldwide obesity has nearly tripled since 1975, with over 650 million adults classified as obese in 2016.

You Are What You Eat

The researchers also found that diet played a significant role in the length of the MC4R+ cilia. Rats on a high-fat diet experienced a faster rate of cilia shortening, while those on a restricted diet had slower shortening. Interestingly, rats that were placed on a restricted diet for two months saw a regeneration of their MC4R+ cilia, suggesting that dietary changes can have a profound impact on the brain’s ability to regulate metabolism and appetite.

This finding is particularly relevant in light of the growing popularity of intermittent fasting and calorie restriction diets. While the mechanisms behind these diets are not fully understood, the Nagoya University study suggests that they may work, in part, by promoting the growth and maintenance of the MC4R+ cilia in the hypothalamus.

The Leptin Connection

The study also sheds light on a phenomenon known as leptin resistance, which is commonly observed in obese individuals. Leptin, a hormone produced by fat cells, signals the brain to reduce appetite and increase metabolism. However, in obese individuals, the brain becomes resistant to leptin, leading to a vicious cycle of increased appetite and decreased metabolism.

The Nagoya University researchers found that rats with artificially shortened MC4R+ cilia were resistant to the effects of leptin, even when the hormone was administered directly to their brains. This finding suggests that the age-related shortening of MC4R+ cilia may be a key factor in the development of leptin resistance.

“In obese patients, adipose tissue secretes excessive leptin, which triggers the chronic action of melanocortin. Our study suggests that this may promote the age-related shortening of MC4R+ cilia and put animals into a downward spiral where melanocortin becomes ineffective, increasing the risk of obesity,” explained Dr. Manami Oya, the first author of the study.

A Message of Hope

While the findings of the Nagoya University study are complex, the message is simple: our brains play a crucial role in regulating our weight, and by understanding the mechanisms behind middle-age weight gain, we can develop more effective strategies for preventing and treating obesity.

As Professor Nakamura notes, “Moderate eating habits could maintain MC4R+ cilia long enough to keep the brain’s anti-obesity system in good shape even as we age.”

This message of hope is particularly important in light of the growing obesity epidemic. By empowering individuals with the knowledge and tools to maintain a healthy weight throughout their lives, we can reduce the burden of chronic disease and improve the quality of life for millions of people around the world.

As we continue to unravel the mysteries of the brain and its role in regulating metabolism and appetite, studies like this one from Nagoya University will play a crucial role in shaping the future of obesity research and treatment. By understanding the complex interplay between our brains, our diets, and our bodies, we can develop more targeted and effective interventions that promote lifelong health and wellbeing.