Every time we think back on a memory, like graduating high school or meeting someone for the first time, our brain changes it a little bit whether by filling in gaps or losing information with each recollection. Having bad memories can be particularly overwhelming though, taking up space in the brain that ends up overcoming our thoughts. Now, neuroscientists from Boston University demonstrate that it’s possible to tone down the intensity of negative memories by stimulating happier ones instead.

Memory can enhance our lives yet also make things worse, especially if it’s scary or we remember things incorrectly. Scientists agree that this doesn’t have to be the case.

“Memory is less of a video recording of the past, and more reconstructive,” says Steve Ramirez, a Boston University neuroscientist and College of Arts & Sciences assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences.

There could be a way to use the flexible nature of memory as a way to cure mental health disorders like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that debilitate people’s lives. After years of studying memory in mice, the team has been able to finding a starting point for this research, discovering where the brain stores positive and negative memories, but also how to block out negative ones more.

In this newest paper, Ramirez and team were able to clearly identify notable molecular and genetic differences between positive and negative memories. They ultimately find that memories are incredibly distinct from not only each other, but other brain cells in general.

“That’s pretty wild, because it suggests that these positive and negative memories have their own separate real estate in the brain,” says Ramirez. “So, there’s [potentially] a molecular basis for differentiating between positive and negative memories in the brain. We now have a bunch of markers that we know differentiate positive from negative in the hippocampus.”

Once the researchers realized they had this foundation, they created a memory and labeled it in mice. To do this, they exposed the mice to either good or bad experiences, such as eating food they like or receiving an uncomfortable shock to their feet.

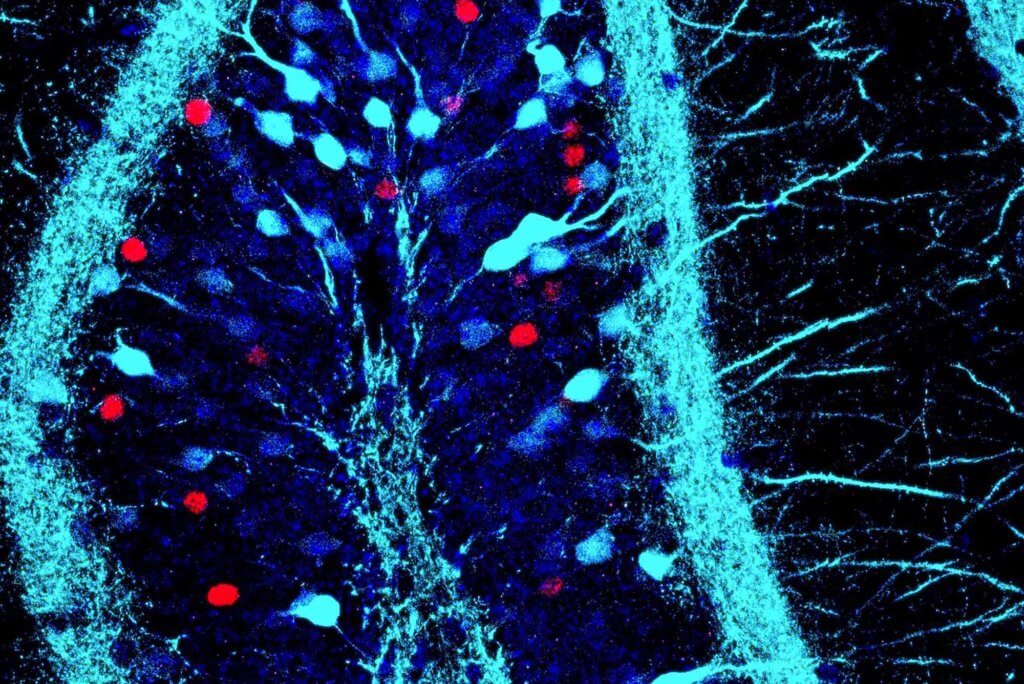

Once they formed a new memory, the scientists were able to seek out the network of cells that are associated with remembering that experience, and have them glow a color that is detectable. From this, the researchers were able to use laser light to activate the memories and artificially change them by turning down the emotional intensity. They found that this intervention changed negative memories permanently.

Ramirez explained that other studies have used similar techniques with other issues, such as deep brain stimulation to help people overcome disorders like PTSD that wreak havoc through bad memories. More researchers are opening up to the idea of more invasive approaches like these. In the future, Ramirez hopes that his teams’ work inspires other neuroscientists to continue to push the envelope with more invasive and hands-on alternatives. “We want game changers, right? We want things that are going to be way more effective than the currently available treatment options,” he concludes.

This study is published in the journal Communications Biology.