“This is your brain on drugs.” If you’re a child of the 80s, you can likely remember the vivid images portrayed to demonstrate the long-term effects of drugs on the human brain. The behavioral effects of drugs on the brain have long been evident. The physical effects, however, have been harder to track. Recently, researchers have used mice to study dopamine neuron structure, addiction, and the brain’s ability to recover.

Researchers from the University of Chicago and the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory detailed, for the first time, specific changes that occur in the brains of mice exposed to cocaine. The research provides new insights into the function of key dopamine structures. These structures are involved in multiple functions, from involuntary movement to behavior.

In a recent paper, the researchers describe how they are adding to the development of highly detailed and accurate 3D maps of every neuron in the brain and their connections. For their contribution, the team identified how dopamine is transmitted across neurons.

“Evidence suggests that these neurons dump dopamine into extracellular space, activating nearby neurons that possess dopamine sensing receptors,” says Gregg Wildenberg, a lead researcher on the project, in a statement. He adds “…they don’t make typical connections, so we wanted to step into this area to see how it actually worked.”

Another motivation for the project was to understand dopamine’s involvement in addiction. What, if any, anatomical changes in dopamine circuits are caused by drugs of abuse, like cocaine? Exploring these details required the use of a three-dimensional serial electron microscope.

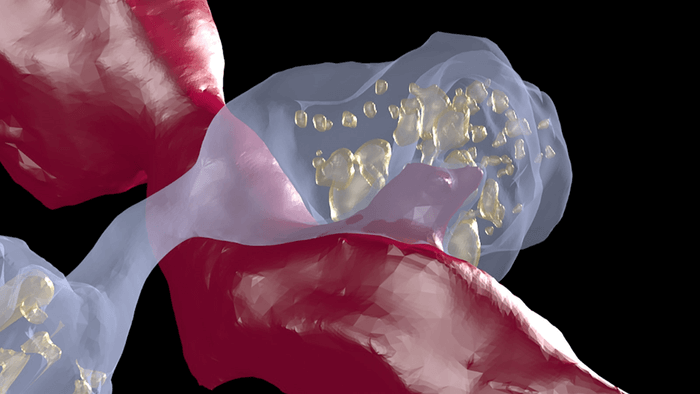

Using resources from the University of Chicago, the team acquired ultrafine samples from the midbrain and forebrain, areas most associated with dopamine. The overall process created a 3D volume that allows researchers to identify and trace different anatomical features of the dopamine neurons, which had proven challenging in the past.

The researchers were able to identify swelling in dopamine-release sites. They were also able to determine that dopamine does not interact normally with neurons, as suspected. Neurons typically branch out like trees to deliver signals. These branch-like tendrils are called axons. After exposing the mice to cocaine, the team found an increase in that branching. The researchers also observed swelling within the axons themselves, an unexpected finding.

“Now we know that there is an anatomical basis to drugs of exposure,” notes Narayanan “Bobby” Kasthuri, a co-investigator on the project. “These animals received one or two shots of cocaine and already, after two to three days, we saw widespread anatomical changes. “It’s not like some molecules are changing here or there. The circuit is rearranging much earlier and with much less exposure to the drug than anybody would have thought.”

While the study has helped clarify questions of form, function, and dynamics in the dopamine system, it also presents important new questions related to repeated exposure and addiction, as well as treatment and recovery. Now that scientists know how the brain is changed due to drug exposure, perhaps in the future, we can help the brain overcome the structural arrangements for a full recovery.

This research was published by eLife Journal.

Article written by Rhonda Errabelli