Shedding our thick sweaters, heavy boots, and puffy jackets in the spring seems to coincide with shedding some heaviness of mood. Projects we dread, such as home repairs, don’t feel as daunting, and we move our bodies more with less effort. That return of energy isn’t just about fewer layers of wool.

Seasonal changes in natural light — hours more sunlight in summer, less in winter, are associated with changes in behaviors, too. Light affects sleep, when and what we eat, and variations in hormonal activity. Abnormal responses to changes in duration of natural light can occur. Seasonal affective disorder (SAD) is a not-uncommon type of depression associated with less exposure to natural light during winter. It also occurs in geographic regions of greater latitude, which have fewer hours of daylight.

Light therapy is an effective treatment for SAD. It has also proved to be effective for major depression not associated with seasonal changes, postpartum depression, and bipolar disorder. How light therapy works at cellular levels, however, had been a mystery, until now.

In a new study, led by David Dulcis, PhD, a professor in psychiatry at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine, mice were used to demonstrate how some neurons (nerve cells) express different neurotransmitters (chemical messengers) in response to changes in the length of daylight. These changes trigger behavioral changes.

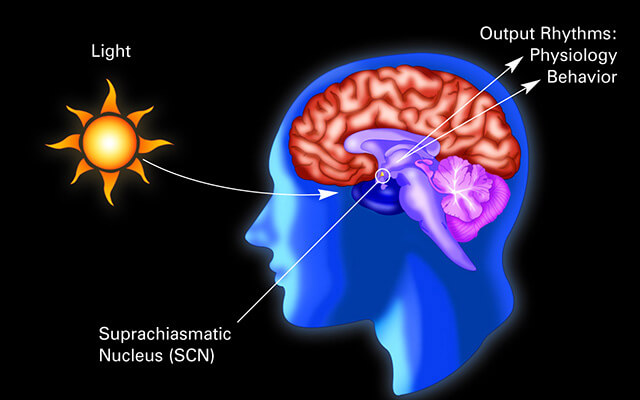

A group of about 20,000 neurons, named the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), lies within the hypothalamus. It responds to signals from specialized cells in the retina which are photosensitive. The SCN has been called the body’s timekeeper because it regulates most of the human body’s circadian rhythms. These physical, mental, and behavioral rhythms follow a 24-hour cycle and affect a myriad of functions. A few of these include metabolism, hormone release, and body temperature.

Dulcis and his research team found that the SCN’s neurons adapt to daylight of different durations, causing changes at cellular and network levels. Specifically, they found that the neurons change in mix and in neurotransmitters, altering brain activity and associated behaviors.

It has been shown that seasonal changes in light exposure also alter neurons in the brain’s paraventricular nucleus (PVN), which has vital roles in managing stress, growth, reproduction, and other autonomic functions.

“The most impressive new finding in this study is that we discovered how to artificially manipulate the activity of specific SCN neurons and successfully induce dopamine expression within the hypothalamic PVN network,” Dulcis states in a news release.

“We revealed novel molecular adaptations of the SCN-PVN network in response to length of day, by adjusting hypothalamic function and daily behaviors,” adds Alexandra Porcu, PhD, a member of Dulcis’ team. “The multi-synaptic neurotransmitter switching we showed in this study might provide the anatomical or functional link mediating the seasonal changes in mood and the effects of light therapy.”

The research paper is published in Science Advances.