That spine-tingling feeling when a musical passage gives you chills, or the surge of excitement hearing your favorite band play live – these intense emotional reactions show how deeply music can move us. Scientists fascinated by music’s hold on the brain and have tried unraveling the underlying neural mechanisms, often using recorded songs. But could live performances more strongly and consistently stimulate the brain’s emotion circuits than listening to one’s favorite album on Spotify?

New research from the University of Zurich that’s now published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests so. The team set up an innovative experiment bringing musicians into the MRI scanner to play music adapted on-the-fly to listeners’ brain activity. Targeting the amygdala – an almond-shaped region central for processing emotions – they found significantly higher amygdala engagement for dynamic live performances of both pleasant and unpleasant piano music.

“Play it once, Sam. For old times’ sake,” Ingrid Bergman famously whispers in the classic film “Casablanca.” That longing for a emotionally charged live rendition taps into timeless social rituals, the researchers say.

“People want the emotional experience of live music,” says cognitive neuroscientist Sascha Frühholz, who headed the study, in a statement. “We want musicians to take us on an emotional journey with their performances.”

Brain Activity During Musical Performances

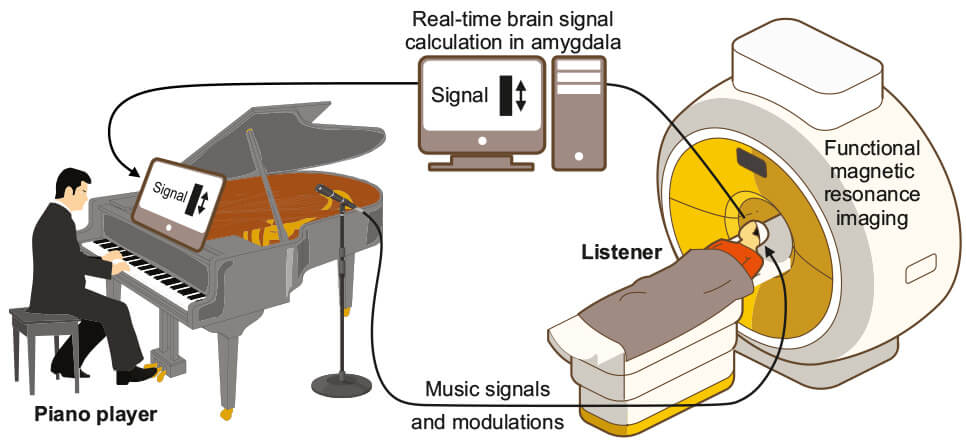

Frühholz’ team designed an innovative experiment to simulate that journey by linking pianists’ performances to listeners’ brains using real-time MRI scanners. Across dozens of musical trials, two pianists alternated between pleasant, calm melodies and ominous, eerie passages composed specifically to induce strong positive or negative emotions.

Critically, the musicians could monitor activity in each listener’s amygdala – which animal research links to fear responses – and modulate their playing to further intensify these neural signals.

Meanwhile, the 27 non-musician participants rated their experience feeling by feeling on emotional scales. Comparing amygdala activations for the tailored live music against pre-recorded versions played without brain feedback showed significantly stronger brain responses to the dynamic performances.

Beyond stronger amygdala activation, live music also switched on more areas involved in musical emotion recognition compared to pre-recorded equivalents. This broader brain network encompasses the auditory cortex, hippocampus, striatum, premotor cortex and frontal areas.

Intriguingly, listening to unpleasant music specifically activated the ventral striatum, which normally processes reward. The researchers speculate unpleasant qualities demand predictive tracking. Pleasant music meanwhile lateralized more to the left auditory cortex, specialized for analytic sound processing.

This emotional synchrony, measurable neurally and subjectively, may be the crux of live music’s enduring appeal over technological reproductions, Frühholz says. The coordinative dance resembles conversational turn-taking or bidirectional bonding vital for social species.

“This can perhaps be traced back to the evolutionary roots of music,” according to Frühholz. Even today’s ever-expanding digital libraries can’t replicate the visceral exchange of musicians adapting pieces dynamically based on audience engagement.

Streaming Music vs. Live Experience

What acoustic qualities distinguish live from recorded performances? Analyzing features like rhythm, pitch and timbre revealed live music has less defined musical structure but more salient emotional cues – amplified dissonance and minor modes conveying sadness in unpleasant songs; brighter, smoother textures for pleasant pieces. Live performances also vary more dramatically in parameters like loudness, tempo and density of notes. These time-changing signatures likely help hold attention and tune brain rhythms.

In the experiment’s key real-time feedback loop, pianists monitored neural activity in each listener’s amygdala alternately during pleasant and unpleasant musical improvisation. They aimed to dynamically heighten this brain response by modulating their playing. Correlating amygdala signals with listeners’ continuous ratings of music emotion and with acoustic properties showed live music evoked mainly positive brain-perception couplings unlike recorded music.

Brain activity also correlated positively with several musical features during live performance, pointing to entrainment between pianists and listeners occurring at neural and musical levels simultaneously.

On the clinical side, closed-loop music performances could have therapeutic applications akin to neurofeedback training. The ability to voluntarily regulate brain rhythms has shown benefits in treating mood disorders. Similarly, tuning music reactions in real-time may elicit targeted emotional transformations. Understanding neurobiological factors differentiating live versus recorded music also matters hugely for designers of emerging immersive technologies aiming to simulate and potentially enhance musical experiences.

We are still far from understanding all the nuances distinguishing a live musical experience. But this research highlights deep commonalities between music and language as communicative expressions of human emotion, with considerable flexibility for sensory and social information exchange. Tracking dynamic loops between performers and listeners will likely unveil further insights into the bonding power of music.