An exciting new prosthesis, implanted in the retina, is restoring some eyesight in seniors robbed of vision by macular degeneration. The thin, pixelated chip could mean reclaiming the ability to read and to recognize faces. Some patients can even gain back their independence, as better vision restores their ability to attend to the tasks of daily living.

In earlier research, Daniel Palanker, PhD, and his team at Stanford University showed that the chip, when used with specially designed glasses, could restore some vision in patients suffering from macular degeneration. A recent follow-up study found that the improvement in vision with the prosthesis integrated with the patients’ normal peripheral vision.

The subjects with retinal implants could simultaneously identify the orientations of colored lines in the center and sides of their visual fields. “That the patients were able to see a coherent image is very exciting news,” says Palanker, a professor of ophthalmology at Stanford, in a statement.

Previous attempts to create functional retinal implants had produced only distorted images.

Macular degeneration affects 11 million people in the United States, most of whom are older than 60 years. It causes loss of sight in the center of the visual fields, what you see when looking straight ahead. Some peripheral vision (at the sides) remains but has low resolution.

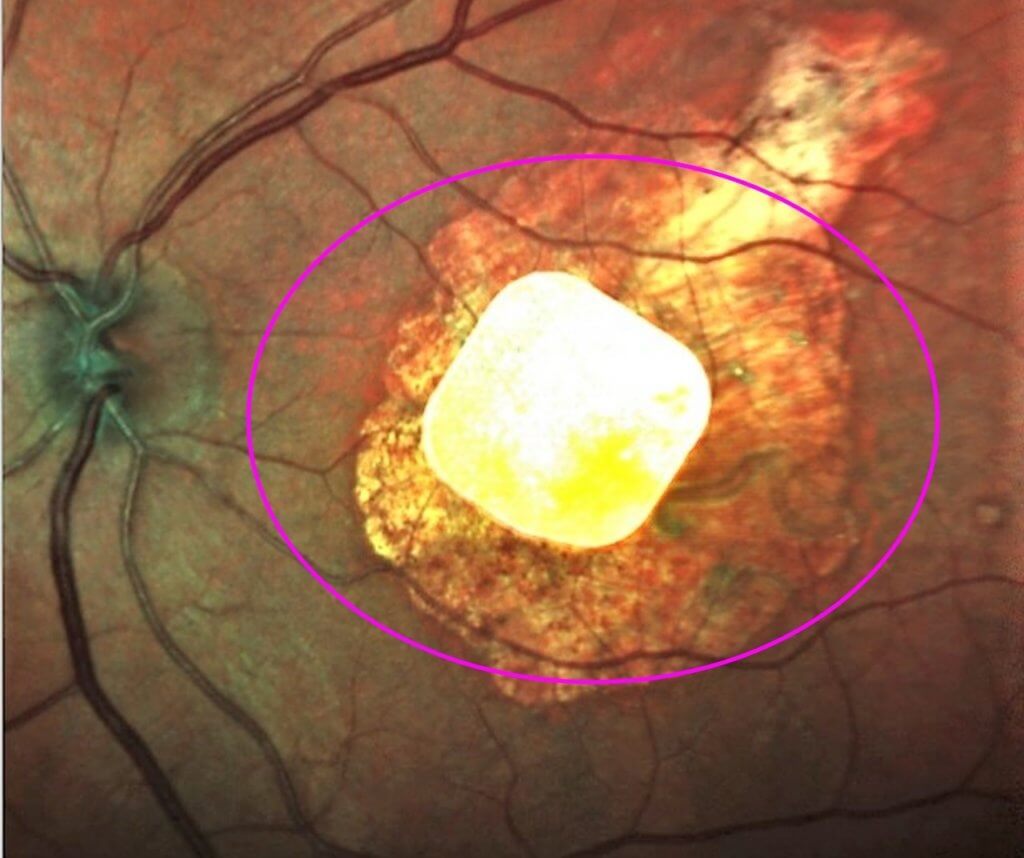

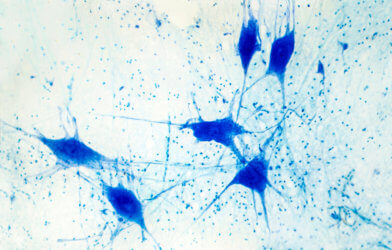

The retina is light sensitive tissue lining the back of the eye. It is the site of photoreceptors which convert light to nerve impulses to the brain. The center of the retina is the macula, which supports the ability to see clearly, with detail. It is tightly packed with photoreceptors.

Macular degeneration is the condition which occurs when the photoreceptor cells in the macula deteriorate. When the cells degrade, the brain no longer receives the information it needs to create a detailed, coherent picture.

Current treatments for macular degeneration can slow the visual decline, but they can’t stop the degeneration or restore sight.

How retina chip implant helps people with macular degeneration

Palanker imagined a retinal prosthesis that would replace photoreceptor cells and take over the light relay. The first step was to develop a thin device that could convert light into electric currents, and could be implanted into the back of the eye. The 1/12-inch pixelated chip sends electrical signals through the retinal neural network to the brain, restoring perception in the center of the visual field.

The team also developed glasses which intensify impulses transmitted to the chip in the back of the eye. “We are replacing lost photoreceptors in age-related macular degeneration with photovoltaic pixels,” Palanker says. “And we activate them with invisible light projected from the augmented reality glasses.”

Palanker, with collaborators in France, recruited five patients, all over age 60, who had advanced macular degeneration with no photoreceptors left in the macula. The patients retained the inner retinal nerve cells that could receive signals from the implant. Surgeons slid the chip underneath the retina.

A few months after the surgery, patients could sense light and see patterns of lines and letters projected from the glasses onto their retinas.

This follow-up study addressed two questions. Would patients be able to integrate their device-enabled, central visual perception with the patients’ own remaining peripheral vision? The initial tests conducted with the virtual-reality glasses explored only whether patients could see the projected lines and letters, while the peripheral natural vision was blocked. Then, would this prosthetic vision last?

The answer to both questions was yes, in the three patients who finished the study. They were able to see images projected onto the implant, and simultaneously use their natural peripheral vision,” says Palanker, “indicating that the brain can perceive the prosthetic and natural retinal codes simultaneously.”

The results were “even better than we expected” he adds.

The prosthetic visual acuity is limited to about 20/460, allowing the patients to see large letters. “This is an exciting proof of concept,” Palanker says. “However, to make it a really useful device and applicable to many patients, we need to improve resolution.”

Palanker’s team is developing an implant with much smaller pixels. It will provide better visual acuity, potentially exceeding 20/100. Future studies are planned.