A baby in the womb reacts to its mother’s voice differently than to a stranger’s voice. An autistic infant doesn’t show a preference for the mother’s voice. Yet later in life, recognizing another person’s identity by emotion or voice, or recognizing speech in a noisy environment are characteristic of autistic perception. Professor Katharina von Kriegstein and her team at the Technical University of Berlin in Germany focused on these two aspects of voice processing. Their findings change the understanding of the origins of the defects of the disease we now call autism spectrum disorder.

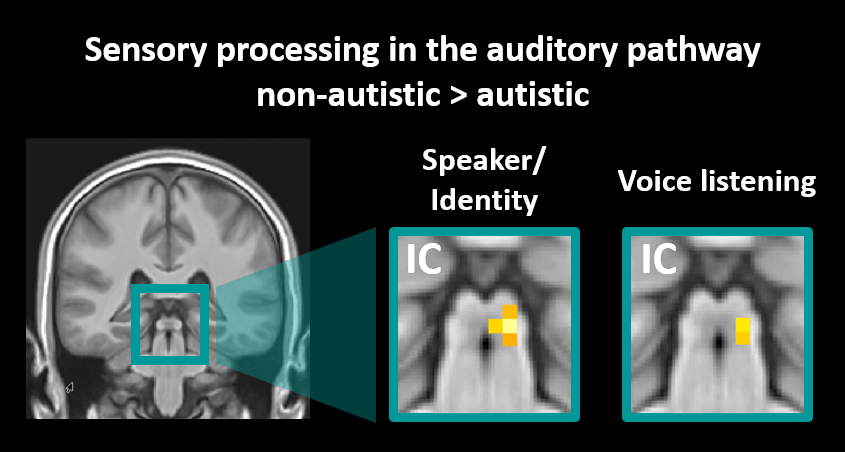

“We found reduced brain responses for autism, as compared to typically developed control groups, in the inferior colliculus – the central midbrain structure of the auditory pathway, but not in other structures of the auditory pathway,” explains first author, Dr. Stefanie Schelinski, in a statement. “The alterations occurred particularly for voice identity processing, but there are also first indications of alterations for speech-in-noise processing.”

It had long been assumed that the difficulties in processing communication signals in autism occurred at either the level of the cerebral cortex or involved structures in the brain associated with the processing of emotions. The reason for such an assumption was that most studies so far had not evaluated the tiny midbrain structures that are essential to sensory acoustic processing.

This very painstaking investigation by the team at TU Dresden, for the first-time, provides evidence that in autism, alterations in the neural processing of voices occur at the earliest processing stages when the sensory signal is first analyzed.

Examining alterations in the earliest sensory processing of the voice when discerning the origins of communication difficulties in autism and other clinical conditions associated with communication impairments holds the potential to create models for both typical and altered communication.

A better understanding of the neural mechanisms associated with autism provides a basis for evaluating additional features of communicative disorders, such as identifying diagnostic markers. Testing impairments in voice identity, vocal emotion recognition, or perception of acoustic voice features such as pitch, can use these new findings as additional tools to diagnose autism.

“It might also be a good basis for evaluating therapeutic options since there is evidence for neural plasticity in the auditory sensory system as the result of training. Further increased basic knowledge about altered voice processing in autism also increases the description and classification of challenges in social communication people with autism are often faced with,” explains professor von Kriegstein, and Dr. Schelinski, on the impact of their findings.

The study is published in the open access journal Human Brain Mapping.