Joy Milne had a nose for disease – specifically, Parkinson’s disease. Scientists discovered that she could “smell” Parkinson’s on people with the degenerative disorder. Intrigued by her gift of sorts, researchers at the American Chemical Society (ACS) in Washington D.C. commenced inventing devices that could (they hoped) diagnose Parkinson’s disease from compounds on the skin which emit odors.

Their efforts have been productive. The scientists developed a portable, artificially intelligent, olfactory (relating to the sense of smell) system, or “e-nose,” that someday may diagnose Parkinson’s in a physician’s office or clinic setting.

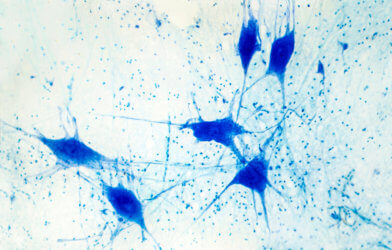

Parkinson’s disease is a nervous system disease marked by motor symptoms, such as tremors, rigidity, and an abnormal gait. Non-motor symptoms include depression and dementia. There is no cure, but early diagnosis and treatment can improve quality of life, lessen symptoms, and lengthen survival. Currently, the disease usually isn’t diagnosed until patients develop motor symptoms, but by that time they’ve already suffered irreversible neuron loss.

Scientists discovered that people with Parkinson’s disease secrete excessive sebum (produced by the skin’s sebaceous glands), and experience increased production of yeast, enzymes and hormones. These combine to produce characteristic odors. Researchers have used gas chromatography (GC)-mass spectrometry devices to analyze odor-emitting compounds in the sebum of people with Parkinson’s. The instruments, however, are large and expensive.

Jun Liu, Xing Chen and colleagues at the ACS wanted to develop a fast, easy to use, portable and inexpensive GC system to diagnose Parkinson’s by detecting odors on skin. The system needed to be be suitable for use in a physician’s office or other outpatient setting.

The researchers developed a device by combining GC with a surface acoustic wave sensor, which measures gaseous compounds interacting with a sound wave. They equipped their invention with machine-learning algorithms and dubbed it “e-nose.”

Using gauze, the team collected sebum samples from the skin of 31 Parkinson’s disease patients and 32 healthy control participants. With the e-nose they analyzed the volatile organic compounds emanating from the gauze. Three odorous compounds were detected from the gauze of Parkinson’s patients; these were significantly different from the control group.

The researchers analyzed sebum from an additional 12 Parkinson’s patients and 12 healthy controls, finding an accuracy of 70.8 percent in predicting the disease. The e-nose had a sensitivity of 91.7 percent in identifying true Parkinson’s patients. Its specificity, however, was only 50 percent, indicating a high number of false positives (samples tested positive when there was no disease). When machine learning algorithms were added, the accuracy of diagnosis improved to 79.2 percent.

Much more research and modifications of the device are necessary before the e-nose is ready for point-of-contact use.

Findings from the researchers are published in the journal ACS Omega.