We’ve reached the point where artificial intelligence can now read our thoughts. International researchers conducted a futuristic study where thoughts were able to control a computer.

Scientists say their technology allowed artificial intelligence to alter images by channeling brain signals from humans. The new study comes from researchers with the University of Copenhagen and University of Helsinki.

“We can make a computer edit images entirely based on thoughts generated by human subjects,” says Tuukka Ruotsalo, associate professor for the Department of Computer Science at the University of Copenhagen, in a statement. “The computer has absolutely no prior information about which features it is supposed to edit or how. Nobody has ever done this before.”

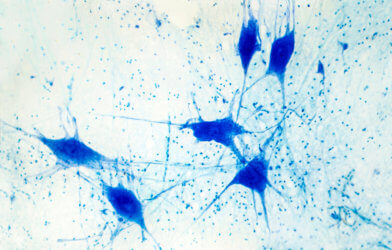

Thirty participants were used in the thought-provoking study. Researchers gave the participants hoods which contained electrodes that mapped electrical brain signals. They were each given the same 200 different facial images to look at and were also given a number of tasks, like looking for female faces, looking for older people and looking for different hair color.

Researchers had the participants look at each image for only a half-second. According to the study, based on the participants’ brain activity, the computer mapped the given preference and then edited the images.

“So, if the task was to look for older people, the computer would modify the portraits of the younger persons, making them look older,” the media release explains. “And if the task was to look for a given hair color, everybody would get that hair color.”

Keith Davis, a PhD student at the University of Helsinki, says the computer “only edited the feature in question.”

“Notably, the computer had no idea about gender, hair color, or any other relevant features. Still, it only edited the feature in question, leaving other facial features unchanged,” adds Davis.

Ruotsalo notes that this type of artificial intelligence could be used in medicine.

“Doctors already use artificial intelligence in interpretation of scanning images. However, mistakes do happen,” explains Ruotsalo. “After all, the doctors are only assisted by the images but will take the decisions themselves. Maybe certain features in the images are more often misinterpreted than others. Such patterns might be discovered through an application of our research.”

However, there are ethical questions having artificial intelligence essentially reading a person’s mind and thoughts.

“Collecting individual brain signals does involve ethical issues. Whoever acquires this knowledge could potentially obtain deep insight into a persons’ preferences,” says Ruotsalo. “We already see some trends. “People buy ‘smart’ watches and similar devices able to record heart rate, etc., but are we sure that data are not generated which give private corporations knowledge which we wouldn’t want to share?

“I see this as an important aspect of academic work. Our research shows what is possible, but we shouldn’t do things just because they can be done,” Ruotsalo continues. “This is an area which, in my view, needs to be regulated by guidelines and public policies. If these are not adapted, private companies will just go ahead.”

The study was presented at the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2022 conference.